Baloch Train Hijack and Pakistan's Derailed War on Terror

The chilling attack is a reminder that conflict resolution cannot be engineered at the cost of an angry population.

advertisement

When the news of an entire train being hijacked in the rugged, mountainous terrain of Balochistan first broke, the thought that crossed my mind instantaneously was, ‘This is Pakistan’s Kandahar moment.’

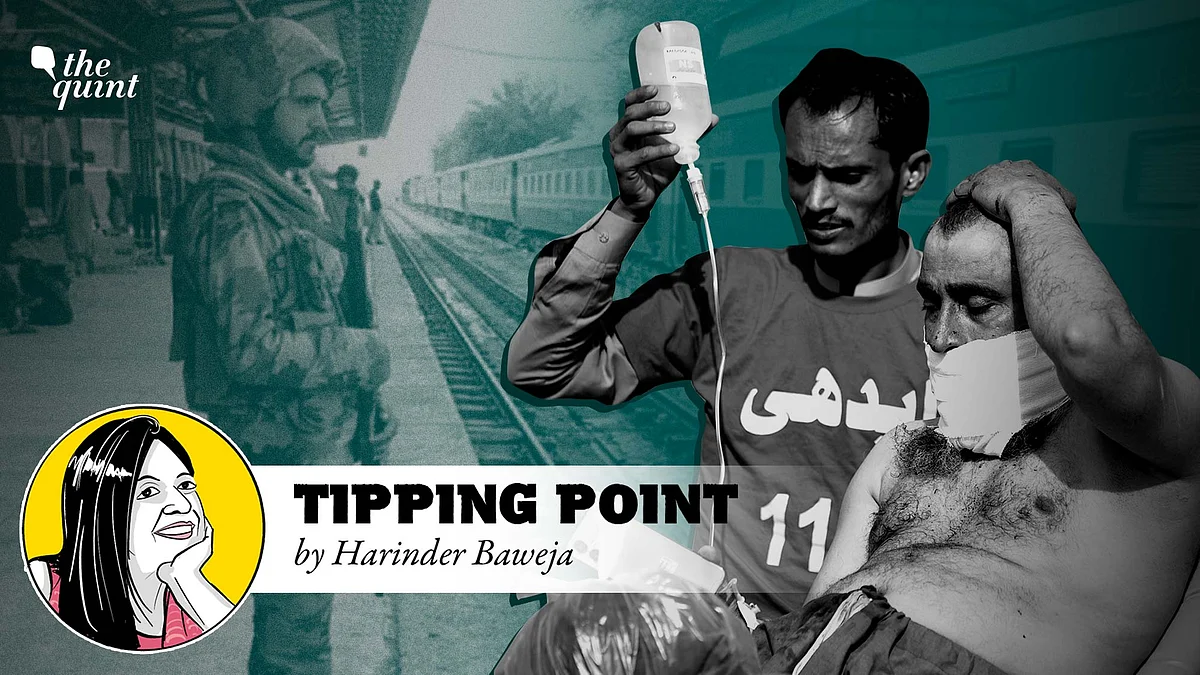

Quite similar to how the Indian Airlines plane was hijacked from Kathmandu to Kandahar at the turn of the millennium in 1999, the Jaffar Express—ambushed in the middle of the afternoon of 11 March 2025—was taken over by armed militia. Like in the case of IC 814, the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) held guns to the heads of frightened civilians and asked for arrested fellow militants to be released.

The Pakistani army launched a counter-offensive and ended the crisis after a tense standoff that went on for 36 hours. The operation left 33 terrorists and 21 passengers dead. According to the military’s media wing, four military personnel were killed in one of the most brazen attacks.

Never before in Pakistan’s history has an entire train been hijacked, though the same train, Jaffar Express, has been attacked several times. And this latest tryst with terror has derailed the security situation in Pakistan. The BLA which claimed credit for the train hijacking, and the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), both pose a threat that has increased not just in scale but also in its sheer intensity.

War Games

Soon after the rescue mission was completed in the late hours of 13 March, Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) Director General, Lt General Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry, indicated that the rules of the game now stand changed.

Since then, Pakistan has been caught in a deadly vortex of violence in which suicide bombers have been detonating themselves outside mosques and at the gates of various army installations. The rules are being set, not by the State, but by gun-wielding militias.

India paid a heavy price after it was forced to exchange three high-profile terrorists in return for passengers aboard the hijacked flight which stayed parked in Kandahar for an entire week. Maulana Masood Azhar, one of the most indoctrinated terrorists India was forced to release at the time, went on to form the Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) soon after. The Jaish, in fact, introduced suicide bombings in Kashmir, where an insurgency took root in 1989.

While levels of violence in Kashmir are on the decline, the opposite is true for Pakistan, which continues to export terror into Kashmir. Various politicians and army chiefs have – over the years and decades – framed the issue of Kashmir as the unfinished agenda of Partition.

In recent weeks, however, Pakistan has faced a surge in terrorism, ranging from suicide bombings to lethal assaults on its military bases. The escalating violence in Balochistan, and in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, ruled by former cricket captain and prime minister Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), has exposed the army’s weakening grip.

As per the Global Terrorism Index (GTI) 2025, Pakistan ranks as the world’s second most affected country, after Burkina Faso. According to GTI, terrorism-related deaths have shot up by 45 percent in 2024 to 1,081. The number of attacks too have seen a sharp upwards trend, going up from 517 to 1,099.

Unfinished Business

The train which was hijacked, started its journey from Balochistan’s Quetta and was to cover an approximate distance of 1,600 kms, before reaching Peshawar, the capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK). Terrorism has travelled the same distance and the constant attacks in both Quetta and Peshawar signal a crisis that has now reached breaking point. Enroute lie Lahore and Rawalpindi, powerful domains of Pakistan's Chief of Army Staff, General Asim Munir.

“I’ve always maintained that the real unfinished business of Partition is Balochistan,” former diplomat Vivek Katju told The Quint, soon after the Pakistani military signalled an end to the train hijack crisis. But as Katju—a strategic expert on Afghanistan and Pakistan— points out:

It would be easy – and tempting – for General Munir to pat himself on the back by only looking at the plain statistics that have emerged from the train hijack. The death toll could have been higher, given that there were close to 500 on board the train that was stopped in its tracks. Already, the actual number of deaths revealed by the military’s media wing are at variance with passengers aboard the train.

Going forward, the army has no choice but to take the fight against terrorism to BLA and TTP’s doorsteps, but the journey is riddled with complex issues. While the BLA is fighting for a separate, autonomous homeland, the steeped-in-religion TTP is fighting an ‘Islamic’ war.

According to G Parthasarathy, who served as India’s high commissioner to Pakistan (incidentally during the Kandahar hijack crisis and the Kargil war), “Balochistan has been a continuous problem and remains a thorn that pricks the shoulder of an Army dominated by the province of Punjab.” Speaking to The Quint, he added, “Pakistan is in deep trouble. They are perennially bankrupt and Munir lacks the sophistication of his predecessor, General Qamar Bajwa. He is no Musharraf either, who saw some wisdom in engagement and negotiations.”

The military-only approach has compounded Pakistan’s war against terrorism. There is an urgent need to formulate a holistic counter-terrorism policy. The policy, which will be dictated by the barrel of the gun must also, necessarily include a humanitarian approach.

“The military mind only understands the power of might but Balochistan needs political initiatives. Politicians should be in the forefront of negotiations. They have the art of give and take,” says Shahzeb Jillani, Karachi-based senior journalist who hosts a television show for Dawn News.

Jillani, who spoke to The Quint, is not off the mark. Insurgencies—like the one India has had to contend with in Kashmir— are rooted in a history of domestic grievances.

The Baloch Question

Balochistan is one of the poorest, least developed provinces in Pakistan despite being the largest.

The province abounds with minerals and natural resources, including gas and copper but none of the benefits accrue to the Baloch population. The resentment has only built up over the decades. The Baloch accuse the army of human rights excesses including the disappearance of many who have tried to raise their voice against the oppressive methods of the State “occupying” their land and their assets.

Instead of listening to the voices from the ground—essential for crafting a sound counter-terrorism doctrine—the Army has encouraged its friend and ally China to build infrastructure projects like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The Gwadar port too has been handed over to the Chinese and the Baloch grievance is that while it stays arid and thirsty, water is being diverted to feed the Punjabi elite.

Fuelled by deep-seated anger and alienation, the Baloch insurgency which started as a slogan for autonomy in 1947, has witnessed several phases, in which violence has ebbed and flowed. The train hijack has loudly announced the fact that it is now a full-blown insurgency.

The BLA, which in the recent past, aimed their guns at Chinese citizens, is now flush with sophisticated weapons left behind by US troops who withdrew from Afghanistan.

This March, a female suicide bomber detonated herself in Kalat, killing a law enforcement officer. In 2022, a lady teacher rammed her explosive-laden body into a van carrying Chinese nationals in Karachi.

The Baloch separatists have demonstrated their growing lethality and—in the process—pointed at how the army and the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Pakistan’s intelligence agency has failed to keep pace. Not only do the insurgents have better weaponry, they also have the advantage of knowing the terrain.

The the decision to hijack the train, forced to a halt near a tunnel in a rugged area far removed from the growing world of internet—which would have aided the rescue operation—speaks volumes about the sharp minds behind the guns.

Turn the Page

Pakistan, headed by prime minister Shehbaz Sharif, is only a political pawn in the hands of Munir. National security has always been the army’s firm domain.

Conflict resolution cannot be engineered. It, most definitively, cannot come at the cost of an angry population, pushed so far back into the wall that it decides to scale it instead, with increased force and firepower. Balochistan, over the last ten years, has had six different Chief Ministers, all chosen by the army.

Munir needs to get down to the task of addressing the serious threat posed by the BLA and the TTP. The fact that the two have a tactical alliance makes the fight tougher. The train hijack signalled a dramatic escalation. The ball now is squarely in Munir’s court.

As he instructs his troops to place their fingers on the trigger, Munir would perhaps do well to also turn the page back and review the peace efforts pursued by General Pervez Musharraf, one of his own predecessors. He may then find that the present is often embedded in the past.

(Harinder Baweja is a senior journalist and author. She has been reporting on current affairs, with a particular emphasis on conflict, for the last four decades. She can be reached at @shammybaweja on Instagram and X. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined