Can an Algorithm Decide Who Belongs? Maharashtra’s AI Experiment

The attempt at introducing AI for migration control illustrates how the State is embracing emerging technologies.

advertisement

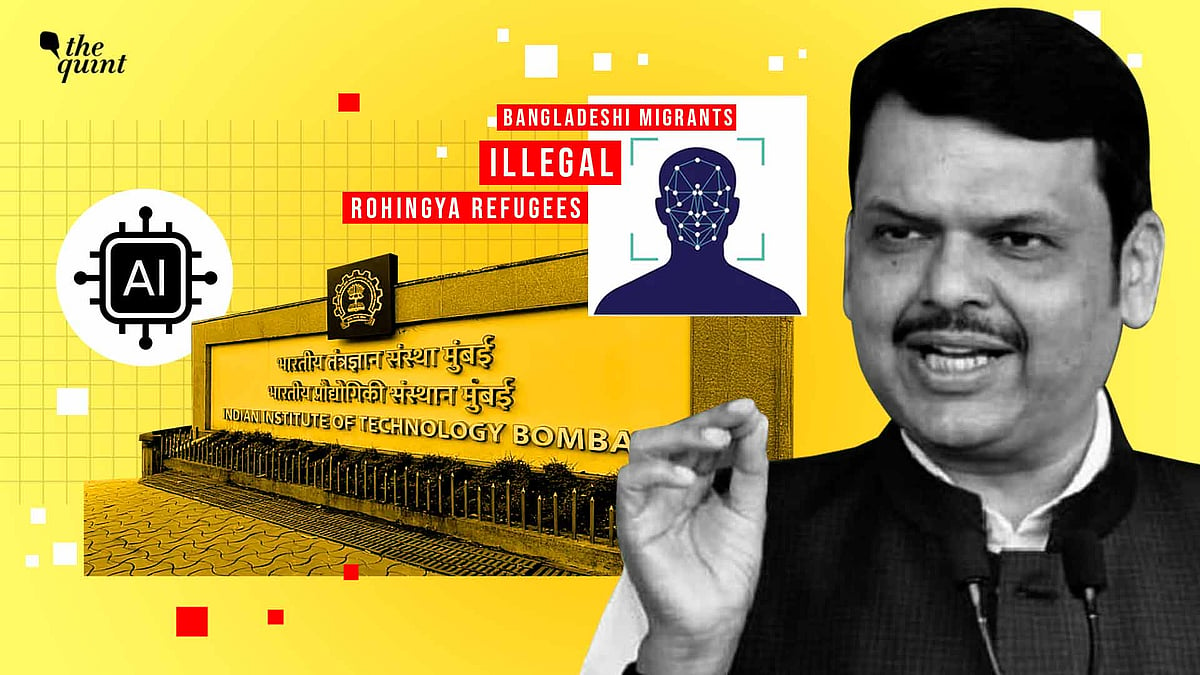

The Chief Minister of Maharashtra recently indicated that the state government was in the process of developing an Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enabled tool in collaboration with IIT Bombay. This tool’s stated purpose is to help identify allegedly “illegal” Bangladeshi migrants and Rohingya refugees.

The AI tool will purportedly be used for verification and will aid the police by conducting a preliminary screening, following which the police will undertake a document verification of the individual to determine nationality.

This latest attempt at introducing AI for migration control illustrates how the State is actively embracing emerging technologies. Several experts have already raised concerns about how the AI tool will distinguish between different regional variations, dialects, and accents of the Bengali language. Experts have also pointed out concerns that language does not have strict demarcations that conform with state borders.

Why AI Is Never Truly Neutral

Presumably, the most alluring aspect of an AI-enabled tool in carrying out State functions is the objectivity it promises. But it would be remiss to not acknowledge that AI systems are far from neutral or objective. At their core, these systems rely on datasets that are collected, curated, and labelled, determining what is treated as ‘normal’ and what is flagged as ‘suspicious’.

Speech recognition systems have already been flagged as being biased and riddled with errors in other countries where they have been deployed. But unfortunately, despite research indicating that AI systems internalise bias and perpetuate discrimination, governments have continued to push for its inclusion in state architecture. Similarly, the Maharashtra government’s move is not an isolated experiment, but rather is in tandem with a broader governmental push to embed AI within policing and the justice system.

A significant worrying aspect in the announcement of the development of the AI tool is the absence of any firm legal grounding for its introduction. The Central government has repeatedly shown its reluctance to introduce any legislative framework that would appropriately regulate AI. The India AI Governance Guidelines, released in November 2025, clearly stated that “a separate law to regulate AI is not needed given the current assessment of risks” and that the risks associated with AI can be addressed through voluntary measures and “existing laws.”

Further, the state government recently approved plans for setting up a permanent detention centre for foreign nationals, with the Chief Minister confirming the same. This demonstrates how emerging technology such as AI is being harnessed to feed vulnerable individuals directly into the pipeline of the carceral state.

Screening Before Verification

Notably, in June 2025, the Maharashtra government had ordered extensive scrutiny of identity and eligibility documents of welfare scheme beneficiaries to identify alleged “illegal” Bangladeshi immigrants.

This supposedly relied on paperwork, database checks, and administrative verification. Now, it seems as though the AI-based speech analysis tool has been incorporated within the process as a convenient next step. Instead of checking documents, the state has sought to use emerging technology for the initial screening, which determines who deserves further scrutiny.

However, deciding who enters such a pool of scrutiny is not a neutral or merely ‘technical’ choice when this process is driven by datasets whose composition remains unclear. As already noted above, this raises critical questions on how dialects are classified as “Indian” or “foreign”, and how these judgments are recorded, categorised, and trained into the system. Thus, a system presented as an efficiency-enhancing measure is, in effect, a system that legitimises suspicion and justifies subsequent questioning.

Anthropologists have already flagged that persons from areas near state borders will be the most susceptible to being misidentified as their manner of speaking, accent and dialect are likely to be akin to people from the other side of the border. International non-profit, Human Rights Watch, observed that when Indian authorities expelled hundreds of Bengali Muslims to Bangladesh in the past, many of them, in reality, were Indian citizens from states bordering Bangladesh.

Constitutional Limits on Algorithmic Policing

While we do not condone the introduction of AI tools in governing sensitive, high-risk matters such as citizenship, if such tools have to be introduced, then they must align with constitutional principles and be rights-respecting. Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to life and personal liberty to all persons, including non-citizens.

In the landmark judgment of Selvi v State of Karnataka (2010), the Supreme Court recognised the importance of the standard of ‘substantive due process’ in forensic practices. The court held that the threshold for examining the validity of all categories of governmental action that tended to infringe upon the idea of personal liberty, must be read with regard to the various dimensions of personal liberty as understood in Article 21.

While details about the implementation of the tool are still unclear, the veneer of objectivity presented by AI tools cannot diminish that emerging technologies are still fundamentally experimental in nature. They are simply assumed to be accurate and credible while continuing to be without any regulatory oversight or independent evaluation.

Several questions continue to linger such as the kind of redressal mechanism that would resolve claims of incorrect identification by the AI tool. The form that such a redressal mechanism would take, what other forms of evidence such as documents and witness testimony would hold in the face of contradictory results from the AI tool continue to persist.

(Avanti Deshpande is a Legal Counsel at the Internet Freedom Foundation. Jhanvi Anam is a Policy Counsel at the Internet Freedom Foundation. The views expressed above are the authors' own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)