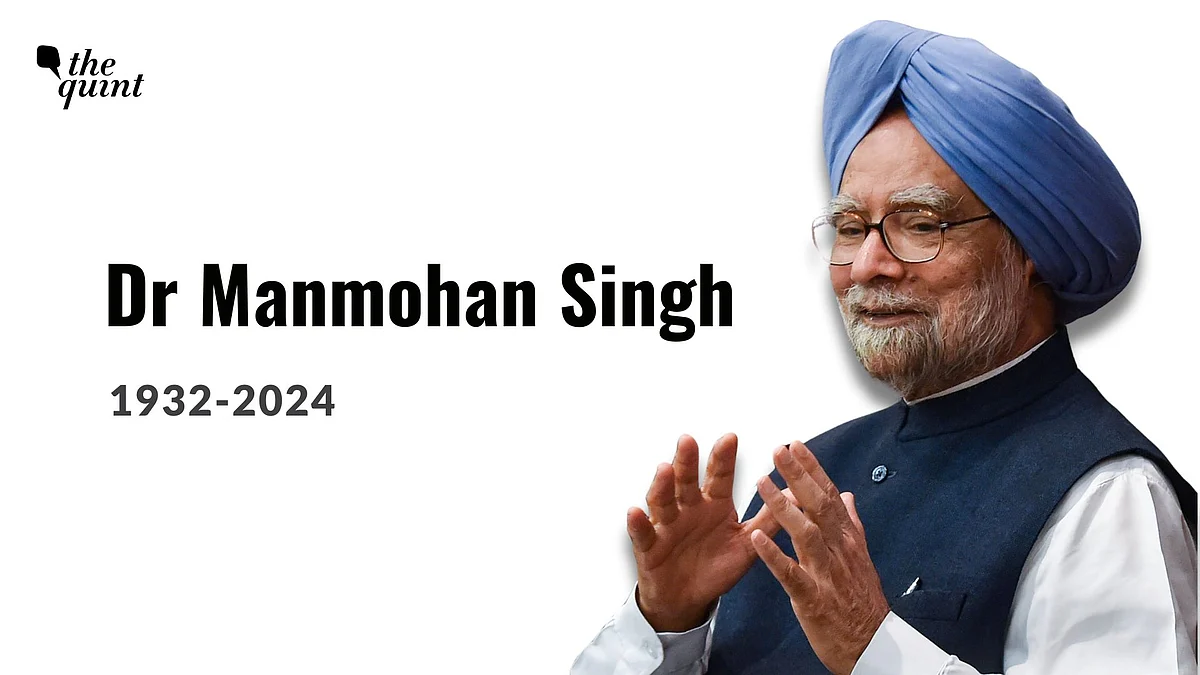

The Legacy of Manmohan Singh: A Leader India Will Miss

Brilliant economist and underrated politician — there are many qualities that Dr Singh will be remembered for.

advertisement

The architect of India’s economic reforms, the first Prime Minister from a minority community, the first Prime Minister outside Nehru-Gandhi family to finish two complete terms, a scholar, economist, technocrat... Dr Manmohan Singh will be remembered for these and many such achievements and qualities.

The former prime minister breathed his last in Delhi on Thursday, 26 December. He was 92. He is survived by his wife Gursharan Kaur and three daughters.

And as the prime minister from 2004 to 2014, he gave the country such important schemes as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, the Right to Information Act, and the Food Security Act, along with such strategic pacts as the nuclear deal between India and United States.

While he had his fair share of critics when he was the prime minister, hardly anyone could dispute his personal sense of decency and honesty.

Humble Beginnings

Singh was born in September 1932 in Gah in undivided Punjab (now in Pakistan). He spent a large portion of his childhood in a humble village that did not boast of any modern amenities. Journalist and author Rasheed Kidwai writes that Singh’s village did not have electricity and piped drinking water. Neither did it have a school, which meant that as a child, Singh would have to walk miles to reach an Urdu medium school in the area. Lack of electricity saw Singh study at night by the light of a kerosene lamp.

During the Partition, his family migrated to Amritsar.

But coming from modest home only pushed Singh to pursue and excel at academics, and he went on to become a star student, studying economics at Panjab University. Later, he pursued higher educational degrees in economics from Oxford and Cambridge. At a public event in 2018, Singh spoke of how he had been encouraged to go abroad by his teacher in Hoshiarpur, SB Rangnekar, remembers historian Ramachandra Guha, who was present at the event.

Singh also went on to become a teacher at Panjab University. Later, he taught at the Delhi School of Economics and even had a stint in the United Nations between 1966 and 1969.

Transforming India’s Economy

Singh’s involvement in shaping India’s economic policy actually predates the 1991 reforms. In the 1970s, he worked with the finance ministry as chief economic adviser and then as secretary.

In 1980, he worked with the Planning Commission before being appointed as the governor of the Reserve Bank of India in 1982. Between 1985 and 1987, he was deputy chairman of the Planning Commission.

Apparently, Singh didn’t believe it when he was told that Rao wanted him to be the finance minister.

Singh told British journalist Mark Tully in 2005,

But he couldn’t have had a tougher task at hand.

In 1991, India's fiscal deficit was close to 8.5 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and India’s foreign reserves were barely enough to pay for two weeks of imports. In return for funds, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed several conditions on India involving opening of the economy.

And Singh did precisely that. As finance minister, he broke down what was pejoratively called the “licence permit raj” and reduced state control of the economy.

As part of this process, Singh slashed import taxes, removed several obstacles to foreign investment, and began the process of privatising public sector companies.

In many ways this captured the beginning of India’s growth story.

An Underrated Politician

Even though PV Narasimha Rao was sidelined in the Congress party after his term ended, Singh’s fortunes continued to rise.

In 1998, he became the leader of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha, ahead of many others in the Congress who were senior to him.

Besides his participation in Parliamentary politics, one of his major political achievements in this period was how he helped seal the alliance between the Congress and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). The DMK was an ally of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at that time and very few expected that it would ever join hands with the Congress or vice versa. But Singh’s gentle persuasion helped convince DMK chief M Karunanidhi to switch sides.

This provided a glimpse of how Singh was actually an underrated politician.

A Tenure of Welfare and Growth

During the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, the face of the Congress-led Opposition was party president Sonia Gandhi. But when she ‘sacrificed’ the top job after the victory, she picked Singh as the Prime Minister.

Besides Gandhi’s backing, a good equation with M Karunanidhi and Communist Party of India (Marxist) general secretary Harkishen Singh Surjeet also worked in Singh’s favour.

In their first term, Singh, along with the former finance minister P Chidambaram, presided over a robust period of growth for the Indian economy. In 2007, India achieved its highest GDP growth rate of 9 percent and became the second fastest growing economy in the world.

Another landmark event in Singh’s first term was the 2008 Indo-US Nuclear Deal, which helped end the world community’s nuclear discrimination against India, besides addressing growing India’s energy needs. It was a personal battle for Singh as his government’s survival was in danger due to the withdrawal of support by the Left parties.

Dogged by Controversies

Riding high on the economic growth and welfare schemes of his first term, Singh led the UPA to a victory in the 2009 general elections, trumping the LK Advani-led NDA, and the Left and Bahujan Samaj Party’s Third Front.

However, his second term was dogged by a number of controversies – from allegations of corruption in the granting of 2G licences and coal blocks to the Commonwealth Games, to the Telangana agitation, protests in Kashmir and tensions with Pakistan.

The Anna Hazare-led Lokpal Bill agitation accused the government of high-level corruption, weakening its credibility.

The inability of Singh and Sonia Gandhi to politically counter these challenges eventually added to the UPA’s unpopularity, culminating in a massive defeat at the hands of the Narendra Modi-led NDA in the 2014 general elections.

He was probably right. At a time when India faces an economic slowdown, many would remember how Singh put India on the path to economic growth in 1991 and saved it from a global recession in 2008-09.

Singh was fiercely critical of the Narendra Modi government’s economic policies and had rightly predicted that demonetisation would adversely affect India’s economic growth.

He went to the extent of calling it an act of “organised loot and legalised plunder”.

Singh continued to work till the end and weeks before his death, he took up the responsibility of guiding the Punjab government on how to deal with the economic fallout of the COVID-19 crisis.

With his death, India has lost not just a former PM and politician, but one of its sharpest minds on matters of economics and governance.

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: 27 Dec 2024,07:00 AM IST