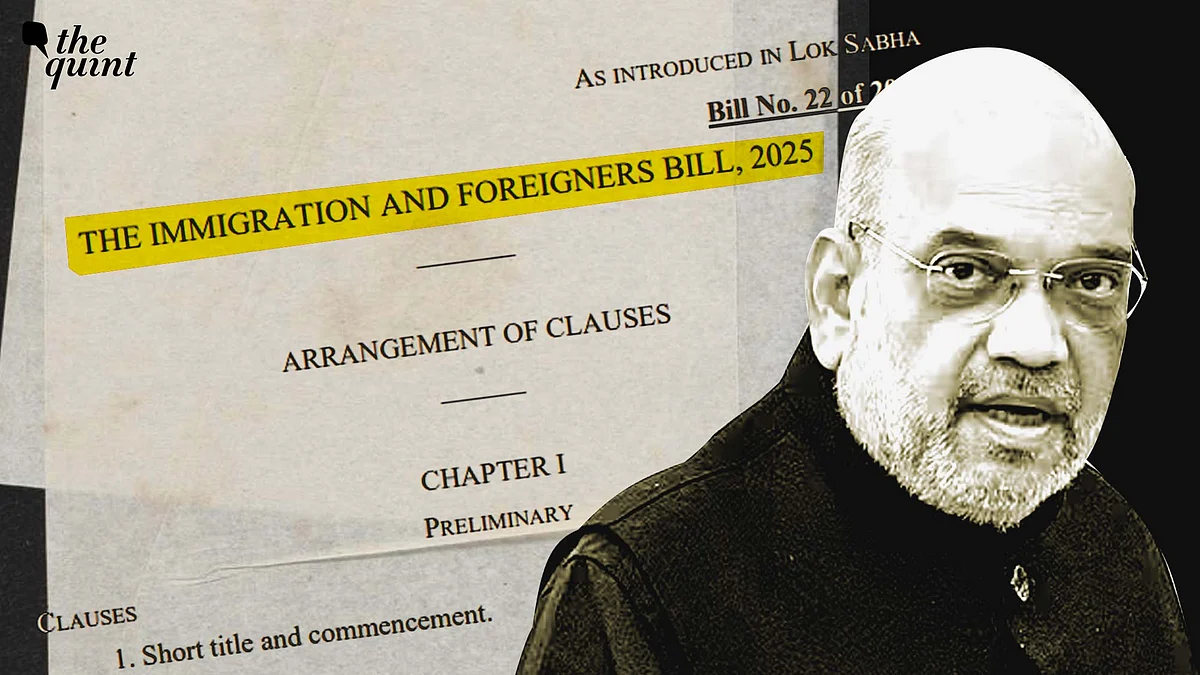

Immigration and Foreigners Bill: A Tool To Muzzle Dissent?

The Opposition alleges that the new Bill, passed in Lok Sabha on 27 March, provides absolutist powers to the Centre.

advertisement

"The ruling government works only for optics and acoustics," says senior Supreme Court advocate Sanjoy Ghose while speaking about The Immigration and Foreigners Bill, 2025 – a controversial legislation passed by the Lok Sabha on Thursday, 27 March.

The Bill, introduced by Minister of State for Home Nityanand Rai, spells out the guidelines that foreign nationals will have to adhere to and the penalties they will face for violating the norms that validate their stay in India.

However, several provisions in the Bill have drawn the ire of the Opposition, which alleges that it provides absolutist powers to the Centre to stem dissent by essentially "kicking out" any foreigner that criticises the government.

Does the Bill Provide Absolute Powers to the Centre?

To start with, there are already four legislations in place to administer the entry and exit of foreigners. These are:

1. Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920

2. Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939

3. Foreigners Act, 1946

4. Immigration (Carriers' Liability) Act, 2000

The Immigration and Foreigners Bill, 2025, includes several existing provisions delineated in these four acts, which raises the question: Why is a new Bill required?

"While the Bill is shaped as a compendium to replace four existing acts, the provisions of various regulations and orders under those acts have been incorporated into an architecture of command and control," senior Supreme Court advocate Sanjay Hegde tells The Quint.

"Those who pose a threat to national security will not be allowed to enter the nation. The nation is not a dharamshala. If someone comes to the nation to contribute to the development of the nation, they are always welcome," Home Minister Amit Shah had said while arguing in favour of the Bill in the Lok Sabha on Thursday, 27 March.

Secondly, the legislation states that immigration officers will have the authority to arrest foreigners, including Overseas Citizens of India (OCIs), without a warrant if they are suspected of having violated the country's immigration laws.

Hegde argues that such provisions tend to make the bureau of immigration "all powerful" and without appellate controls.

As the law currently stands, if a person's OCI card application gets rejected, they have the right to file a revision petition with the Centre within a period of 30 days or a review petition under Section 15 (A) of the Citizenship Act.

Similarly, if a foreigner's visa application is rejected, they have the right to appeal against the decision by writing to the consulate within 15-30 days, providing evidence that the visa rejection is erroneous.

However, the new Bill makes an immigration officer's decision final and binding, thus taking away a foreigner's right to appeal their decision.

"The government doesn't want any legal proceedings or appeals and their goal is to directly cancel an OCI card or visa," senior Supreme Court advocate Sanjoy Ghose tells The Quint, adding, "Through this Bill, the appeals process is essentially bypassed."

Further, speaking about the "umbrella" powers given to immigration officers to make arrests, Ghose says that the officials already had the power to arrest errant foreigners under the four existing laws that deal with such issues, further highlighting whether there was any necessity for a new Bill.

The government has, however, argued that the Bill was necessary to streamline the existing laws and simplify them by creating a single, modern framework. A few provisions have also been added in the new law, such as revised penalties for foreigners who come to India without valid documents or those who use forged documents. Imprisonment durations and fines have also been revised for those who stay beyond their visa durations.

Furthermore, the Bill requires educational institutions, hospitals, nursing homes, et al, to report the enrolment or admission of foreigners to immigration officials.

However, what is unclear is why these provisions couldn't be included in the existing four laws by introducing simple amendments in Parliament.

'PR Strategy to Brand Foreign Journalists as National Security Threat'

The Bill is also predicted to compound the woes of foreign journalists stationed in India – some of whom have faced cancellations of their work permits and OCI cards in the recent past.

Sébastien Farcis, a French journalist who had been living and working in India since 2011, left the country in June last year after the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) refused to renew his work permit in March, just ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections.

Farcis, a former OCI card holder, says that he had obtained all the necessary visas and accreditation to work as a journalist in the country. He also said that he never worked in restricted or protected areas without a permit, and always respected the regulations imposed on foreign journalists in India.

The MHA's decision had come in the backdrop of some of his articles that may have been viewed as being critical of the ruling establishment.

When asked whether he feels that The Immigration and Foreigners Bill, 2025 will make matters worse for people like him, Farcis, now living in France, said that the MHA didn't even need an excuse to remove him and others like him.

"I feel the Bill is a way to weaponise, to a greater extent, the visas for all the journalists and activists they want to throw out and brand them as a 'national security threat'. It's perhaps a PR strategy because the denial of visas is always possible without any justification," Farcis told The Quint.

Vanessa Dougnac, another French journalist, had claimed that she was forced to leave India in February last year after receiving a notice from the MHA. Dougnac said that the MHA's notice accused her reportage of being "malicious" and "harming the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India"

However, on Thursday, 27 March this year, she put out a statement saying that she had been provided a one-year permit to resume work in India.

“The Government of India has authorised me to resume my profession as a foreign correspondent based in New Delhi. A one-year work permit has been granted to me by the relevant authorities," the statement read.

Yet another journalist who claims she was "forced" to leave India is Avani Dias – the South Asia Bureau Chief for Australian broadcasting firm ABC News – after she was allegedly denied a visa extension.

Dias also claimed that a Spotify podcast she has been hosting, titled 'Looking for Modi' – which explored the state of Indian democracy and the Centre's alleged attempts at muzzling dissenting voices—was also not favourably looked upon by the government.

"I was told specifically by the MEA [Ministry of External Affairs] that I would not get my visa extension because my reporting 'crossed a line'," she had said while speaking to The Quint in April last year.