The year was 1991 when I landed in the national capital to pursue my graduation at Kirori Mal College (KMC), Delhi University.

Tarun (Bhartiya) was already famous in the college. He was my senior by a year – and had dropped out from Mathematics (Honours) to join afresh and pursue Economics. It was a talking point at KMC as many marvelled at how easily he could drop out of a coveted course like Mathematics.

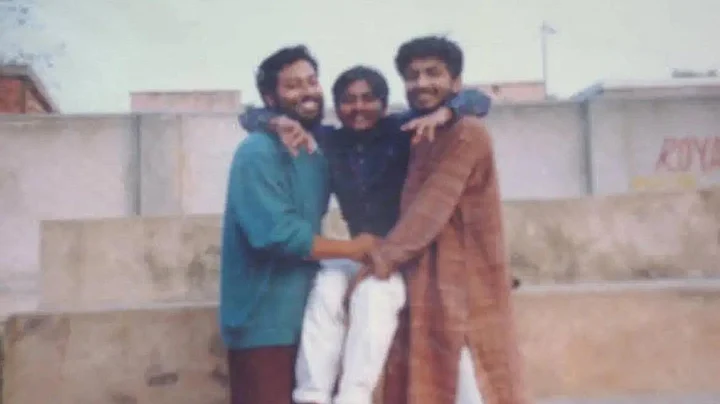

Tarun was the first to approach me and a few of my friends. By then, he had started being known by that moniker he loved in college – ‘Commy’, a slang for Communist. He had an easy way with making friends, striking rapport, and forging conversations.

A Polymath

As a true-blue polymath, Tarun was good at everything – from mathematics, political theory, and theatre to writing poetry in Hindi and publishing in leading journals like Hans. He was also active in quizzing, debating, and was the student president of The Players, the still active theatre society at KMC.

He was a generous lender of his books, patiently explaining and introducing us to thinkers (like French Marxist scholar Louis Althusser and others) and ideas. It was by no means easy to be living in a hostel, but he was zestful and witty and loved cooking for his friends. He was at ease cracking self-deprecating jokes and was fond of ‘shocking’ us with his bizarre tales, quite a few of which, we now realise, he made up, simply to poke fun at our protected upbringing and the perceivable lack of ease in our cosmopolitan ways.

He once narrated an incident about running away from home, before joining college. He said he had not informed his family and had gone off to pull a rickshaw and live among the rickshaw pullers.

When I asked him about the difficulties of living such a life, he would offer details and remarkable insights. Like how their work took a toll on their sexual lives. Some of these stories jolted us out of our comfort zone and compelled us to think – 'Why would somebody do such a thing?'

Tarun would also take great pleasure in telling us how upset his father was but how his mother had always attempted to understand his brewing anarchist ideologies. He always loved to tilt the balance out of the ordinary.

Being with him, one would often realise that his personality was not just a result of conscious, premediated curation. Much of it came to him naturally – as part of his very being.

He was simply not happy or satiated with the mundane, and had the courage of conviction to not only argue for but also live the very life he fought for. He would experiment with himself in ways that others would defer from.

He would invite us to his room, to regale us with stories of his unrequited loves, and how he was chased away from girls’ hostels. He would then cook for us, and drink to glory.

Art of Compassion

I remember him directing the play The Vagina Monologues. It was a play about experiencing sex, sensuality, reproduction, vaginal care, menstruation, through the lens of women.

He conducted a workshop for many of us to prepare us for the play, but we struggled to make sense of what it meant or why he wanted to experiment with such ‘out there’ topics.

In fact, most students never could make any sense of it and, if memory serves me, he even ran into problems with the college administration over it. He would later laugh at how irked the administration was at the themes he picked while wondering how parents of the girls involved in the play would respond to it.

Tarun also made great posters. After the demolition of Babri Masjid, he spent all night making posters on communal harmony, which we went and put up across the walls of Delhi University. His sense of aesthetics came from his compassion. He was almost always the first one to respond to terrible incidents – no matter where in the world.

Tarun was a spendthrift and generous with sharing his money and resources with friends. Even as an undergrad student, he had a large collection of books. When he later shifted to the hostel, he would often come to my room when he was pensive. He wouldn’t say much but would ask for music, smoke a cigarette (in fact quite a few), and immerse himself in a book.

A Lone Ranger

I often asked him if anarchists also thought of their health and body as something to defy and bring down! On rare occasions, Tarun would speak about himself. I don’t know if it was the anarchist in him or some other aspect of his being but, despite his outgoing nature, in his heart of hearts, I knew he remained a loner.

He had his struggles with the world. One does not know if that sense of being a loner resulted from his rebellious attitudes, or if he took to rebellious ways to cope and overcome that inner loneliness. Since many of us would often idolise him, I was struck by this vulnerable inner self.

Once, while walking back from Kamla Nagar Market near North Campus, we had to part ways, but he asked me to come up to his room. He said in colloquial Hindi, “I would be broken, if I were to walk back alone.”

Is it perhaps this sensitivity that made even his detractors respect him in college. There was nothing mediocre about him that could be despised. Tarun overcame all of his prejudices and saw life for its “big picture”. That is why he could easily accommodate a large array of students from varying backgrounds.

He always shied away from praise and accolades. I suspect he saw power and privilege in it.

In keeping with his ways, Tarun moved to doing film and television, worked for a while with NDTV, and moved out of Delhi. He went back to Shillong where he'd spent his childhood. He chose to be away from the mainstream gaze and went on to make documentary films on local knowledge systems, culture, and everyday life of the Northeast.

I kept in touch – and would meet him whenever I had an occasion to visit Shillong. When I shared with him that I was looking for a cover photo for my book on emotions, he readily shared his photos and promised to send high resolution versions once I selected one of them.

Tarun was not just brilliant; he made it a point not to flash it and went the and extra mile not to stand out. Alas, in this, he seems to have failed, given the volume and intimate nature of the tributes that have been pouring in on social media since the news broke.

The beauty of these tributes is that many come from people who never even met Tarun personally – and only knew him through his posts, and comments on social media. But they felt it as a personal loss.

I wonder if history has the time and place to record these intimate lives that hid behind the pale of the ordinary.

Tarun Bhartiya passed away in Shillong on 25 January following a heart attack. He was 54.

(Ajay Gudavarthy is a political theorist, analyst, and columnist in India. He is associate professor in political science at Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. This is an opinion piece. All views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)