“What do you miss now?” a journalist from the US had once asked Phoolan Devi, years after she quit being a dacoit and became a Member of Parliament. "The power and authority," she had said. "When people betray me now, like those bastards at Channel Four, [the filmmakers]… if I were still a dacoit, I could have taught them a proper lesson."

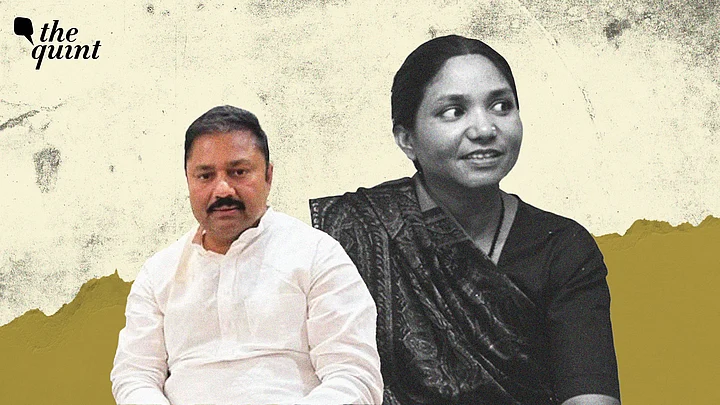

It isn’t hard to guess, then, what her reaction would have been today, had she tuned into the recent podcast by her convicted killer Sher Singh Rana with influencer Shubankar Mishra in which he talks with (caste) pride about why he killed her.

Over the two-and-a-half-hour-long podcast, the duo repeatedly debase Phoolan with casteist and sexist slurs. But it’s not just casual casteism and sexism. Rana peddles lies about Phoolan and distorts facts. Thus, it becomes important to counter some of his claims.

In his first salvo against the woman he killed 24 years ago (which the duo offensively refer to as ‘thokna’), Rana claimed that Phoolan and her team used the movie The Bandit Queen to peddle their false propaganda, and that they killed the Thakurs only to get her revenge for her own rape, not the rape of multiple women. He vehemently dismissed the mass rape allegations, brushing them aside as a “lie”. He said that any villain in history could be whitewashed through movies—and that his biopic is waiting to be released in a few days.

This cannot be more untrue. Phoolan had serious objections against the depiction of Mallah women in the film and the rape scenes. From 1994 to 1996, Phoolan Devi and her legal team filed various lawsuits to ban The Bandit Queen before its release and to delete the rape scenes.

They even filed a lawsuit at the Supreme Court after the film's release, despite the global acclaim it received. The High Courts ruled in favour of her but the SC dismissed her petition in the name of "cinematic freedom."

Her objections to the rape scenes were not due to shame. She did not like the way an oppressed woman’s body was exploited by upper caste directors for profitable gains. The film and its opposition by Phoolan sparked debates about the ethics of depicting real-life individuals, especially victims of trauma, in cinema in those days. She strongly campaigned for her bodily dignity in the 90s—way ahead of the times.

But this was one fight she lost, unlike her war at Bhemai, Uttar Pradesh, where she roared like a lion and oversaw the killing of her rapists and their enablers in 1981. At one point, Phoolan even threatened to immolate herself in front of a theatre which premiered the movie. From The New York Times to The Guardian, many international news media reported on her legal fight for dignity. Alleging that she used the film to whitewash her story is thus baseless.

Rising from Ashes: Victim to Gang Leader

Phoolan Devi doesn’t need any introduction. Everyone knows her. She was born as Phoolan in a remote lower-caste village in Uttar Pradesh. Devi was affixed to her name by the people who loved her and accepted her as the reincarnation of Goddess Durga who slaughtered her upper-caste perpetrators of gender violence.

Her life took a dramatic turn when she was abducted by a gang of dacoits headed by the upper-caste Babu Gujjar. What followed was a harrowing journey of survival, violence, and retribution. She was brutalised for three continuous days by Gujjar, who saw her as nothing more than a disposable body. But Phoolan Devi was not one to be broken. Instead, she channelled her rage into a fierce determination to fight back.

Born into the Mallah community, a marginalised caste in Uttar Pradesh, Phoolan Devi’s existence was shaped by the dual tyrannies of caste and gender. Yet, she rose from the ashes of her torment to become a symbol of defiance, a voice for the voiceless, and a thorn in the side of India’s oppressive power structures.

In the heart of India’s oppressive caste system, where the weight of centuries-old hierarchies crushes the spirits of millions, Phoolan Devi emerged blazing—a woman who refused to be extinguished. Her life was a saga of unimaginable suffering, unrelenting resistance, and an unquenchable thirst for justice.

Rana’s podcast is not just an insult to her memory; it is a calculated attempt to dehumanise her and delegitimise the struggles of oppressed communities.

Overall, it eulogises the “achievements” of Rana and his self-kidnapping, B-class cinematic jail break drama, passport and visa scams, impersonation fraud and so on. Mishra consistently points out that Rana ji is from Uttarakhand, “jahan ki mitti mein fauji ki khushboo hai”. He portrays Rana as a staunch nationalist who would do anything for his country.

The entire narrative is aimed at legitimising the murder of Phoolan Devi and portraying it as a “patriotic” and “nationalist” act. “Joh ek fauji karta hai woh sahi hi hota hai, nah?”

Rana says that he was falsely booked for her murder. But he was the one who had surrendered to Uttarakhand police, claiming to have killed Phoolan to avenge the killing of Thakurs at Bhemai. His confession was publicly recorded by the media at the Dehradun Press Club.

Rana claimed in the podcast that most of the dacoits in Phoolan Devi’s group belonged to lower castes and that the slain Thakurs were “poor, innocent farmers”. This is far from the truth. The group was initially led by Babu Gujjar, an upper caste man. He was killed by his right-hand man, Vikram Mallah from the Scheduled Mallah caste, who then became the head of the largely upper caste dacoits' group.

Mallah was killed by Lala Ram and Sri Ram, the two Thakur men who were also part of the same gang and in whose absence Vikram had killed Babu Gujjar. They could not accept the fact that a lower caste man became their leader. Also, most upper caste gangs didn’t allow women in their groups. They despised Phoolan, the young lower caste girl getting prominence in the gang.

Deputy Commandant Raghunandan Sharma, who had hunted down 365 dacoits in the Champa valley, said in an interview to The Atlantic in 1996 that every upper caste village wants one of its members to join a gang, so that the village is protected.

“It's often said in the ravines that if a man is blessed enough to have three sons, one will join the uniformed service, the armed forces or the police; one will stay at home and till the land, and the third will become a dacoit. The first will thus give the family legal authority, the second the assurance that the land will not go to waste, and the third will guarantee the social prestige of the family. And there is a second set of dacoits who become such to fight for land rights.”Deputy Commandant Raghunandan Sharma

After dismissing her rape, the infamous jail breaker and passport forger, the “patriotic” Rana, changes his stand in the middle of the podcast and claims that Phoolan was raped but not by the villagers who are Thakurs but by her own gang men who were lower castes.

But her oppressors were her own upper caste gang members Sri Ram and Lala Ram, the Thakurs who blindfolded her and kidnapped her to Bhemai and kept her in a dark hut and raped her for three weeks. Bhemai was a Rajput village with an all Thakur population of around 400. It was really small and people knew each other and protected the dacoits. They enabled the rape and also took turns to rape her for three weeks.

She was not even 18 at that time. Even minor boys were motivated to rape her and they did. It can be said that caste solidarity prevailed over the village’s collective sense of morality. Phoolan remembered every one of them that touched her or mocked at her while she was paraded naked in the village. It’s a curse for both, Phoolan and the Thakurs. But that’s what makes the Bhemai “kaand“ interesting, in the infamous terminology used by Shubankar Mishra.

Phoolan Devi’s most infamous act of retribution—the Behmai massacre—was a direct response to the violence inflicted upon her. It cannot be understood without acknowledging the systemic violence that shaped her life. Phoolan Devi was not just a bandit; she was a rebel who dared to challenge the entrenched hierarchies of caste and gender.

Both Rana aka Sanjiv Gupta and Mishra are Savarna and do not understand what systemic caste violence means. They belong to the groups that (directly or indirectly) wield power over the oppressed.

The Weaponisation of Disinformation

The rise of right-wing propaganda in India has created a dangerous environment where disinformation is weaponised to distort history and silence marginalised voices. Influencers like Mishra, with their large followings, have become conduits for this propaganda. Their podcasts and videos often feature individuals who perpetuate casteist, sexist, and communal narratives, all under the guise of “free speech.”

This is not just an attack on Phoolan Devi; it is an attack on the millions of Dalits, lower-caste individuals, and women who continue to fight for their rights in India. It is important to note that Phoolan Devi was anti-right wing and anti-caste.

Her rise as a bandit queen and her killing of her rapists had created a sense of fear in the North Indian Hindi belt. They could not accept the existence of Phoolan Devi nor could they see her thriving as an MP and helping Bahujan and Dalit women.

Had she been alive today, she would have been a strong symbol of justice and equality and an icon of gender liberation. This thought bothered the upper caste men and became the main reason for her death. Even today, it is the same thought that urges men like Rana and Mishra to desecrate Phoolan’s legacy and her memory.

Despite her extraordinary life and contributions, Phoolan Devi’s legacy is often overshadowed by sensationalised narratives that reduce her to a mere bandit or a figure of controversy. This erasure is not accidental.

We should also keenly note that even though Phoolan Devi died 24 years ago, she lives in the memory of the people of India and across the globe, as a symbol of resistance against caste-based gender violence.

Phoolan’s story can motivate any woman in India to fight against systemic oppression. The right-wing is aware that even though Phoolan Devi is no more, her legacy remains powerful, vibrant and nurturing—and they want to erase this legacy through lies and propaganda.

The podcast is part of a larger trend of right-wing influencers using their platforms to spread disinformation and perpetuate casteist and patriarchal ideologies. By giving a voice to Phoolan Devi’s killer while silencing her own story, Mishra and others like him are complicit in the erasure of her legacy. This is not just an insult to Phoolan Devi’s memory; it is an attack on the very idea of justice and equality.

Why Phoolan Devi Matters Today

In a country where caste and gender-based violence continue to plague millions, Phoolan Devi’s story is more relevant than ever. She was a woman who refused to be a victim, who fought back against her oppressors, and who sought to create a more just and equitable society.

Her legacy teaches us that no matter how oppressive the system, it is possible to rise above it and fight for a better future. It also reminds us of the importance of telling our own stories, of reclaiming our narratives from those who seek to distort and erase them.

Phoolan Devi was not just a woman; she was a movement. Her life and legacy are a testament to the power of resistance and the enduring struggle for justice.

As we remember her, we must also confront the forces that seek to diminish her legacy. Phoolan Devi was, and always will be, The Bandit Queen—not because she was a criminal, but because she dared to defy a criminal system. And for that, she will forever be a legend.

(Shalin Maria Lawrence is a writer, social activist and columnist based in Chennai. She is an intersectional feminist and anti-caste activist. This is an opinion article and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)