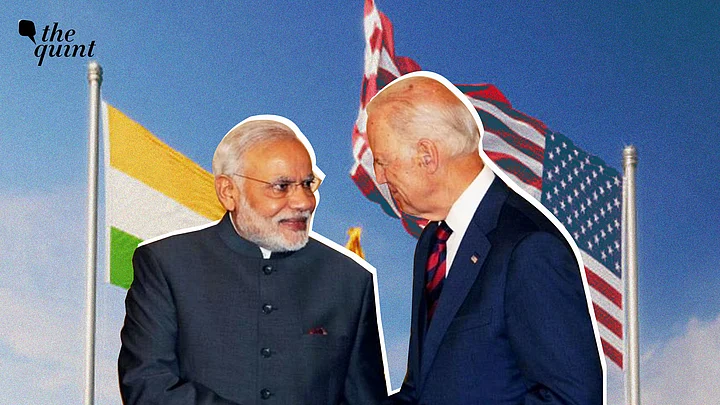

The Quad grouping will graduate from the last virtual meet of four leaders to the physical summit on September 24, when US President Joe Biden will be hosting Japanese outgoing Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in Washington DC.

But then Quad has been a doubters’ paradise ever since it was coined due to its slow and lackadaisical growth and the lack of an interactive matrix, or, for that matter, a commitment to the cause. This changed with the virtual summit in March. While for the US, especially under former President Donald Trump, the grouping had to be directed against the malignant growth of China, the other three wavered. Now, even the Biden administration appears to overtly decline it as being against any country and reiterate that it was not a security-focused anti-China group.

Semantics apart, the Chinese reaction to the upcoming summit and the Quad smacks of its continuing concerns, while dismissing it as a formation of “cliques” targeting other countries, and a group that “won’t be popular” and has “no future”.

Quad Is Yet to Find a Direction

The Chinese spokesman Zhao Lijian belaboured, “Relevant countries should discard the outdated zero-sum mentality and narrow-minded geopolitical perception, view China’s development correctly and respect people’s aspiration in the region and do more that is conducive to solidarity and cooperation of regional countries.”

Even at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping decried the recently formed AUKUS (Australia, the UK & the US security and defence partnership deal) and the Quad, urging member states “to resist external forces from interfering in our region at any excuse and hold the future of our countries’ development in our own hands”.

The Quad is yet to firmly chart out its contours except for the quest of a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific and calling for China’s adherence to international maritime law and for it to stop “bullying” regional countries and encroaching on their territorial integrity and sovereignty.

But the US appears to be sanguine in confronting China, knowing too well the hesitations and hiatuses in perceptions and approaches of the other three countries. Australia, Japan and India are indeed concerned about Chinese hegemonistic ambitions, but to what extent are they going to go, varies. The current Australian government is broadly in sync with US objectives, but political fortunes do change in democracies. What course the next government will follow is anybody’s guess.

A 'CRIPTAQ' In the Offing?

Meanwhile, Pakistan is also part of a different US-led Quad comprising Afghanistan and Uzbekistan and will continue to leverage US insecurity and the need for continued access to Taliban and Afghanistan. While it will have its iron-clad friendship with Beijing, it will not be an either-or with Washington. Prime Minister Imran Khan is also likely to secure a meeting with Biden finally. Eventually, we may be looking at the evolution of a new informal alliance structure — CRIPTAQ — comprising China, Russia, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, Afghanistan and Qatar.

Parallelly, only last week, the Biden administration entered into a highly charged territory even for its own allies, especially its transatlantic partners, when it signed a far-reaching security and defence partnership agreement, termed AUKUS, with Australia and the UK. It implied Canberra cancelling the $66-billion nuclear submarine project with Paris. France, one of the most prominent powers in the Indo-Pacific, is totally miffed, and called it a “stab in the back”. It recalled its ambassadors from Washington and Canberra.

The European Union has also released its ‘Indo-Pacific Strategy’ which puts greater emphasis on partnership with India and Japan. As such, Europeans have been highly disillusioned by the US-Afghan strategy and its unilateral, chaotic exit from Afghanistan without consulting, coordinating, or caring for the European partners or their concerns. It looked more Trumpian and was not expected of Biden, who was claiming to be “Back to Business” in the international arena. Moreover, multiple Indo-Pacific strategies may act at cross purposes and to the advantage of China, which might find the crevice an effective leeway to exploit the fault lines in the Western camp, as it does with the ASEAN, who are considered central to all approaches.

A Slew of Alignments, Quartets

India is also invested in the Indo-Pacific project but its core concerns, approach and modus-operandi have remained broadly within the contours of Prime Minister Modi’s speech at the Shangri La Dialogue in 2018, which includes a much larger geographical and maritime space from the Middle East to Africa, and looks for an inclusive solution while propagating the “rule of law” in the Indo-pacific. It is the only Quad member country that has both land and maritime contestations with China but has preferred “dialogue over dispute” and “competition with cooperation”, while subtly warning Beijing and confronting where it must.

We are living in an era where multiple alignments, trilaterals, quartets and plurilateral arrangements are becoming the formats for collaboration and international discourse. India on its part has just finished chairing the 13th BRICS summit and participated right after in the SCO Summit, where Afghanistan was a major issue and point of concern and discussion. In addition, India, China and Russia also collaborate within the confines of the RIC, let alone the G20, among others.

India’s strategic relationship with Russia is an eyesore for Americans, who would prefer an alliance with India even if they continue to nurture and enrich their own hi-tech defence and strategic content in the bilateral context.

India has a big defence pie and a huge market in general to keep all stakeholders invested from their own national interest perspectives. How it will calibrate that advantage will be the key to its success.

During the last virtual summit of the Quad, a focus was made on harnessing critical technologies, minerals and rare earth as well collaboration on vaccines and in healthcare. These are critical subtexts for India’s ensuing economic journey and could provide a more beneficial and dependable framework of cooperation, including India developing a robust global value supply chain for vaccine production and healthcare. This could be of direct benefit to New Delhi.

The Significance of Realpolitik

The security dimension of Quad, in any case, will eventually depend on the realpolitik at a given time. The infrastructure initiative may be launched at the Washington meeting, which might prove to be another mega project broadly on the lines of G7’s B3W (Build Back better World), and if conceived and executed properly as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), it might provide newer opportunities to Indian businesses. The White House readout on the Quad summit spells out that it will “focus on deepening our ties and advancing practical cooperation areas such as combating COVID-19, addressing the climate crisis, partnering on emerging technologies and cyberspace”.

Afghanistan is being flagged as a point of major discussion. But for all practical purposes, the four Quad countries have a limited leeway in the evolving scenario in Kabul and in the Taliban ascendancy. The US is trying to keep the “Doha Agreement” and has asked the United Nations to extend the waiver on the travel of Taliban officials, which might have to be handled by India that chairs the UNSC 1267 Sanctions Committee. The US outreach to India by Secretary of State Antony Blinken on the “Over the Horizon” support might be complicated.

India's Options Are Limited. Quad Can't Change That

Practically, the most relevant organisation, whose members are directly impacted by the developments in Afghanistan, is the SCO, aiming at regional security, stability and counter-terrorism. PM Modi in his interventions very clearly reiterated the red lines for the Taliban’s international recognition and the need to counter radicalisation through a common template. India’s stance at the Washington meet will possibly be the same as articulated in Dushanbe quite succinctly.

Even in the Afghan context, quadrilaterals and Troikas are rampant, where India was not an integral part, be it a China-led, US-led or Russia-led initiative; India pitched for an Afghan-led peace process.

Another grouping was formed at Dushanbe, where foreign ministers of Iran (the newest SCO member), Russia, China and Pakistan agreed to stay connected.

No doubt, with the onset of Taliban, toxic complicity and the zero-sum game of Pakistan and China, India’s options are ideational and limited. And at the Quad summit, that won’t be any different.

(Anil Trigunayat is a former Indian Ambassador to Jordan, Libya and Malta and a regular contributor and commentator on foreign policy and security issues. He is associated with several think tanks and the Chambers of Commerce & Industry. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)