Like all regimes, the first NDA government led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee will be remembered in history for some remarkable successes and failures.

The IC-814 hijacking, the burning to death of Australian missionary Graham Staines and his two sons, the terror attacks on the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly and the Indian Parliament, and the 2002 Gujarat riots can be categorised as failures.

Facilitating the telecom revolution, getting rid of the white elephant public sector companies, massive investments in road infrastructure, and the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan can be categorised as successes.

During furious political debates, rival gladiators usually mention these while praising or slamming the Vajpayee legacy.

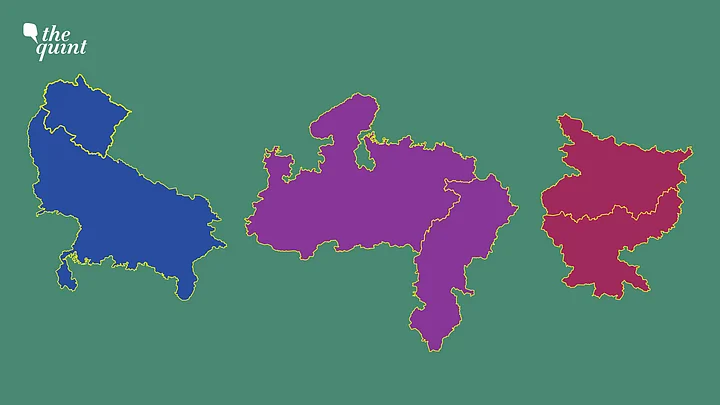

Yet, the authors think that one of the more important achievements of that regime was the smooth manner in which three large states were carved up to create three new and smaller states. It was 23 years ago, in november 2000, that Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, and Chhattisgarh were formally created.

The Economic Trajectory of the Three New States

The new states were created after decades of agitation and protests. The complaint was the same: the regions were neglected by both the political class and the bureaucracy, and the locals of these regions were denied their fair share of political power and economic opportunities.

As the chart above shows, the economic trajectory of the three new states has been quite different. Jharkhand remains a laggard, with a per capita income that is about 60 percent of the national average.

In terms of per capita income, Chhattisgarh was quite close to Jharkhand when both were created 23 years ago. But now, as you can see in the chart, Chhattisgarh has raced ahead of neighbouring Jharkhand.

Uttarakhand, of course, was a unique region blessed by both high-productivity agriculture and religious cum normal tourism.

Nevertheless, its economic performance has been more than impressive with a per capita income that is substantially higher than the national average. We will attempt an analysis of these differences later.

But even a cursory glance at the data suggests that the “new” states are better off than their parents. Of the three new states, Jharkhand is the worst performer with a per capita income of more than Rs 85,000. Yet, that is about 40 percent higher than that of its parent state Bihar which happens to be the poorest state of India now by a wide margin.

Chhattisgarh is neck and neck with its parent state Madhya Pradesh. The outlier is Uttarakhand whose per capita income is almost three times that of its parent state Uttar Pradesh.

Quite clearly, in their own ways, all three states have benefited from the “separation”.

The Gap Between Neighbouring Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh

While analysing the different economic trajectories of the three states created in November 2000, it would be better to look at Uttarakhand from a different lens. It was never a “basket case” the way Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh were.

In many ways, Uttarakhand is similar to another smaller state, Goa, with the latter having the additional advantage of access to the ocean and mineral reserves.

It is the gap between neighbouring Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh that seems surprising. Both were extremely poor states when they were born. Both have suffered the ravages of Maoist terror and violence. Like everywhere else in India, corruption is an indisputable reality in both, as it is in Uttarakhand.

Some analysts wrongly attribute political instability in Jharkhand as a major cause behind its laggard performance. Till 2013-14, there wasn’t much of a difference between the per capita incomes of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand which was wracked by instability between 2000 and 2014. It is 2014 onwards the gap between Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand has been widening by the year.

But it has been stable since then, with a BJP-led NDA government using for a full term of five years till 2019 and then a JMM-led UPA regime all set to complete a full term in 2014. The reason perhaps is something that is not easily measured by data: it is called the quality of governance.

Measuring Governance Isn't Just About Per Capita Incoma

Even at its worst, Madhya Pradesh was far better governed than Bihar. The “hangover” or spillover effects can be seen in the performance of Chattisgarh and Jharkhand. Also, when you look at the trajectory of the three states, it becomes clear that which political party has been dominant is an irrelevant factor.

Uttarakhand routinely alternated between the Congress and the BJP till 2022. It was in 2022 that the BJP retained power.

Chattisgarh had a BJP government between 2003 and 2018 with the Congress as a strong opposition. The Congress has been ruling since 2018 and looks set to retain power in the assembly elections being held now.

Both the Congress and the BJP have been part of ruling regimes in Jharkhand. So, both can be praised and blamed for relative successes and failures.

Poor governance is “measured” or reflected not just through the trajectory of per capita incomes. Since the early 1990s, development economists have echoed that quality of life is more important than just per capita incomes which can be deceptive in countries, regions, or states that display a very high level of income and wealth inequality.

Quality of life takes into account important factors like health, education, and access to basic human needs. For some time, the Niti Ayog has been coming out with a report on multi-dimensional poverty for India and all its states and union territories. The MP Index takes into account 12 major parameters to estimate how many citizens in a given state are multi-dimensionally poor.

There is no doubt that it is a superior and more representative way of estimating and analysing the “economic” performance of various states. In the updated 2023 Report, Niti Ayog has estimated that about 14.7 percent of Indians are multidimensionally poor. The corresponding numbers for Uttarakhand, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand are 9.7 percent, 16.7 percent, and 28.8 percent.

Quite clearly, these broader and more representative numbers reinforce the perceptions created by per capita income estimates and lend them more credibility.

Many More Smaller States Need to Be Created

There is no space here to analyse all the 12 parameters and check how the three states born in November 2000 have performed in comparative terms. The chart above shows comparative performance over three parameters which are lack of access to nutrition, sanitation, and bank accounts.

It is evident from the chart above that all three states have done remarkably well in terms of access to bank accounts. But then, serious analysts know that state governments have not played a significant role in this.

The success is largely due to the phenomenal success of the “Jan Dhan” zero-balance bank account scheme that was launched by the Union government in 2014. Despite facing early skepticism, it has clearly done wonders with 50 crore Jan Dhan accounts and more than Rs 2 lakh crores in deposits.

Yet, even here, the performance of Uttarakhand is three times better than that of Jharkhand. Three adjectives come to mind when one looks at the numbers: Impressive, Average, and Poor. That sums up the trajectory of Uttarakhand, Chattisgarh, and Jharkhand respectively. It is a worrying sign that a quarter of the population is deprived of adequate nutrition and almost one-fifth is deprived of sanitation. These two, together threaten to perpetuate a vicious cycle of poverty.

But it could have been possibly worse if Bihar was still a region of Bihar rather than a state. About 29 percent of people in Jharkhand are multi-dimensionally poor; the figure is about 34 percent for Bihar. In virtually all the 12 parameters factored by the MPI Report, Bihar lags way behind even the second worst performer Jharkhand.

This is not to conclude that Uttarakhand has been an all-round success. It faces severe ecological challenges because of unbridled and illegal “infrastructure” construction.

Similarly, Jharkhand and Chattisgarh confront their own challenges. As do all Indian states. However, the authors are convinced that there is one powerful message that comes from that November 2000 moment when three new and smaller states were created.

The message: many more smaller states need to be created.

It is illogical and perhaps even foolish with massive states like Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, and West Bengal. Carving them and many other states into smaller entities would be a common-sense policy that would benefit all. Even a laggard like Jharkhand has demonstrated that smaller states do better than their larger parent states.

Besides, the creation of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana in 2014 demolished the argument that language must be the basis for a state. People in both Andhra and Telangana speak Telugu and both are doing well.

The problem is: does India have one or a group of political leaders who can launch a nationwide debate and forge a consensus on the creation of smaller states?

No one is visible on the horizon.

(Yashwant Deshmukh & Sutanu Guru work with CVoter Foundation. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)