For several centuries, the devout Hindu headed to the Kumbh festival at Haridwar, Nasik, Ujjain and Prayagraj whenever it is held. But the Maha Kumbh this time was different.

The sacrality of the Ganga, Yamuna, and the imagined Saraswati rivers aside, the public relations campaign surrounding the festival ‘sold’ it as a frenzied phenomenon, inducing a FOMO (fear of missing out) among Hindu masses like never before.

It is another matter that the event – marketed as occurring every 144 years – was also held in 2013, as evidenced by a Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report published by the Uttar Pradesh government in 2014.

Devotion was spiked with unprecedented boasts of world-class facilities of travel and stay, religious greatness, and national pride. The blinding brightness of massive electronic screens and the 360-degree marketing blitz was engineered to overwhelm.

High-decibel speeches from the biggest mascots of the Hindu right-wing exhorted people to attend the Kumbh — or hang their heads in shame. Promises of Japanese-style sleeping pods, luxury tents, smooth crowd control, and every kind of arrangements for pilgrims were made. All one had to do was turn up to the confluence — and watch the magic unfold.

The media, fuelled by generous government advertisements that were integral to the marketing campaign, forgot to do the one job it had to.

It ignored the genuine concerns of overcrowding, kilometers-long traffic jams, and blatant VIP culture that caused immense hardship to lakhs of pilgrims — media coverage of which may potentially have averted future mishaps.

BJP’s Holy Revival Plan

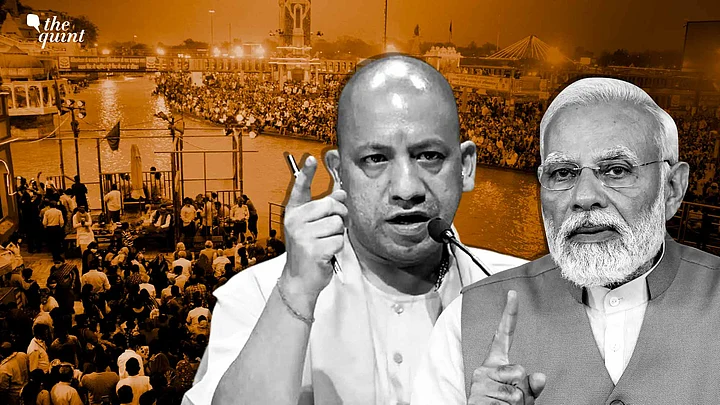

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has attempted to use the Kumbh as a means to recover political ground lost in the 2024 elections – where its Uttar Pradesh tally fell from 62 to 36 seats – and to firmly plant the Hindutva flag ahead of the upcoming Bihar elections later this year, and Assam in 2026.

The tone of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's post-Kumbh letter betrays an awareness of these electoral wounds — and a desire to repair them. Both Brand Modi and Yogi Adityanath took hits, and the Kumbh presented an irresistible opportunity to expatiate political follies.

Chief Minister Yogi, often touted as a potential challenger to Modi, ensured through his frequent visits to Prayagraj that when Uttar Pradesh goes to election in 2027, he would personally be identified with the organisation of the Kumbh. He seems determined that this reflected religious glory would ensure that he is able to hold the state, without which his national ambitions, if any, would not stand a chance.

Yogi's sense of urgency is not without cause.

The Samajwadi Party (SP), rejuvenated after the Lok Sabha elections, has been snapping at his government’s heels. The Congress, too, won more seats in the Lok Sabha than the last two elections combined, including Phulphur (Allahabad), which it reclaimed after 44 years.

SP president Akhilesh Yadav’s attacks over the stampedes at Prayagraj were focused on pointing out that the 2012 Kumbh, held when he was the CM, was much better managed. There is also strong buzz that the UP government might go for a cabinet expansion to address latent resentment, strengthen caste equations, and reward loyalists.

Uttar Pradesh is one state that the BJP cannot afford to take for granted, and while there may be a dissonance between the "double engine" government at the Centre and Lucknow, it is a united front that will ensure the success of the BJP in the next state elections, due in 2027.

Devotion Meets Disaster

In the days leading up to Mauni Amavasya, a particularly auspicious day for ritual bathing, citizens’ videos of mismanagement and administrative failure broke through the gatekeeping protocols of mainstream media. Those who proffered criticism were called anti-Hindu, and silenced. No lessons were learnt.

On 29 January, the gods too seemed helpless in protecting their devotees when the local administration allegedly blockaded roads to ensure that VIPs could ‘earn’ their religious merit undisturbed. The stampede that followed killed at least 35 people — most of them elderly, women, and children.

Denials and dismissals swiftly followed, and politics overtook humanity. The digital, tech-savvy Kumbh administration suddenly had no means, or perhaps no will, to enumerate the dead.

With the crucial Delhi elections around the corner, there was no room for decency or dignity for the dead. Politics is only about winning for those who live. Yogi Adityanath ascribed the tragedy to the huge number of pilgrims, and a gaggle of self-styled godmen spun it in the way they knew best, using religion.

“Dying at Kumbh leads to salvation," said Dhirendra Shastri from Madhya Pradesh, a young Turk among Hindu preachers. The dead were quickly forgotten.

The Prime Minister first appeared at the scene performing the Amrit Snan (rebranded from the Persian Shahi Snan) on 5 February, the day that Delhi voted. A few days later, the BJP returned to power in Delhi after 26 years. Salvation, particularly of the political kind, was undeniably attained.

Victory speeches followed and divine benedictions were evoked; but what remained conspicuously absent were visuals of ministers, even if performatively, visiting the houses of those who died in the stampede. The show must go on, and 140 crore Indians were told to unite in celebration.

On 8 February, the UP government proudly claimed that 40 crore people had already visited the Kumbh, achieving their target with more than three weeks to spare before the final day. The latest figure stands at 67 crore or 670 million. For a government capable of counting pilgrims so precisely, it is baffling that the Census appears to be an insurmountable challenge.

Meanwhile, other warning signs were studiously ignored: videos from different parts of North India that showed people turning on fellow travellers. Breaking windows of train compartments, mobs had a field day and the meek just prayed for their safety and dignity.

The Price of Spectacle Politics

Less than a month after the first stampede, on the cold night of 15 February, another tragedy struck — this time in the national capital’s busiest railway station, where carelessness and callousness by railway authorities cost at least 15 lives. Again, media blackouts were sought to be enforced, and social media companies were ordered to remove critical posts in the name of public order.

The Prime Minister issued a tweet expressing his grief and distress. As always, the consequent blame game drowned the cry for justice and sorrow. The old adage 'speak no ill of the dead' became 'speak not at all about the dead.'

The Kumbh had started out with the excitement of rediscovering a Bharat that loves all paths to salvation, be it that of the Vedas and Puranas, of Budhha, Kabir, Islam, and worships nature in its myriad forms: rivers, trees, plants and creatures.

For young India, it held the allure of romanticised connection to timeless mystics and their eccentricities. It held the promise of finding India’s soul again. And I am sure it met these expectations for many, despite the politics, name-calling, the commercialisation of religion, and the VIP culture.

But it also revealed that public life and political narrative has become almost irredeemably toxic, more than even the Ganga.

Speaking in the Uttar Pradesh Assembly, the Yogi Adityanath washed his hands of the deaths and the stampedes. Deploying philosophy to political use, he said, “Those who were vultures saw dead bodies… those who are pigs saw filth… and those who came with ill-thoughts met with misery."

I guess they didn’t attain salvation, then.

(Valay Singh is a senior journalist and the author of Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)