The hauntingly beautiful quote by Amir Khusrau, the 13th century Sufi poet, scholar, and musician, about the now-troubled Kashmir was, “If there is paradise on earth, it is here. But beneath its beauty lies the resilience of a people who carry diverse traditions with quiet dignity.”

Khusrau's Kashmir has now lost its syncretic soul as abandonment faces its Sufi shrines, ancient Shaivite temples, and its Buddhist stupas.

It is a relatively recent phenomenon of societal regression that can be attributed to unhinged politics, brazen partisanship, and the normalcy of majoritarianism—ably stoked by neighbouring Pakistan to create an us-versus-them narrative that disabled the spirit of Kashmir's resilient people as envisaged by Khusrau.

But, while the finger of blame has justifiably been pointed across the Line of Control (LoC), a certain blame must also accrue to all dispensations in New Delhi, since Independence, without any exception.

Wily local politicians in J&K have their own share to account for. But, in recent times, it is perhaps the redefinition of the pluralistic and inclusive “Idea of India” to the reframing of national politics towards majoritarian identities—as well as suppressing democratic dissent towards what Dr BR Ambedkar forewarned as the “tyranny of the majority”—that has fuelled a centrifugal emotion away from New Delhi.

The only Muslim-majority region of the J&K is naturally susceptible to getting caught in the crosswinds of polarising communalism—as that leads to electoral consolidation and harvest in the “rest of the country.”

Border Realities

Geography and history are instructive of the underlying threats to a land of unmatched diversities like India. Almost all religious and ethnic minorities (who may have commonalities of faith and ethnicities across the border) are predominantly present on the outlying regions of the map of India. Hence, they are vulnerable to centrifugal disillusionment—if not handled sensitively.

Some of the bloodiest insurgencies since Independence have entailed these border regions (populated by national minorities), as the emotional distance and dissonance from Delhi here is easier to imagine.

It is not just the Muslim-dominated Kashmir Valley, but also the Sikh-dominated state of Punjab, Christian-dominated state of Mizoram, or the more complex landscape of Manipur (where a belief of bias by Delhi on account of majoritarian consideration pits one community against the other).

There lurks a dangerous fear of detachment unless its people are deliberately co-opted, outreached, and included with dignity.

Similarly, the Gorkha tensions in the Darjeeling Hills (alongside Nepal border) or the border districts of Assam (alongside Bangladesh) are a tinderbox that needs to be handled with firmness but care, without demonising or “othering” our own.

A New Frontier of Dissent

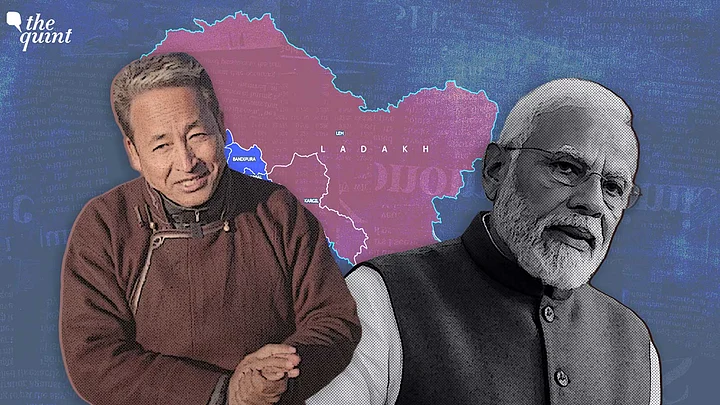

The latest national flashpoint with similar underpinnings of a border region given to ethnic and religious minorities is Ladakh.

The roots of this unrest lie in the same kind of overlooked socio-economic grievances that Delhi has historically chosen to sideline or suppress. A similar dynamic once fuelled the discontent in Punjab when the Centre dismissed the Anandpur Sahib Resolution instead of engaging with it. Later efforts to control Punjab’s politics by “out-muscling” regional parties only deepened the alienation, eventually triggering an armed insurgency that took decades to quell.

In Ladakh, the once-feted activist Sonam Wangchuk led a peaceful hunger strike, seeking redressal of constitutional guarantees, greater autonomy, statehood, and the Sixth Schedule status for Ladakh. But the same-old partisanship, demonising, and intolerant (of democratic dissent) instinct of Delhi that contributed to the ham-handed handling of Manipur recently created a similar unrest, this time in the historically peaceful region of Ladakh.

The curse of lazy promises made by Delhi, only to retract from the same subsequently, and automatically label all those who dissent as “anti-nationals” (read, Pakistani connection), besets the Ladakh reality, too.

Neighbouring J&K Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, who is smarting from the forgotten promises of J&K’s statehood, lamented, “When he (Wangchuk) praised the Prime Minister as an environmental warrior, nobody found fault with him. And when he celebrated in 2019, profusely, for fulfilling the dreams of Ladakhis by granting them UT status, nobody objected either. Today, suddenly, we are told there is a Pakistani connection.”

Even Sonam Wangchuk’s wife, who insisted on his “Gandhian ways” of protest, wondered,

“How can you portray a person as 'anti-national' who has been talking about making shelters for the Indian Army, and boycotting Chinese goods?”

A Dangerous Pattern

Obviously, Sonam’s arrest (that too under the National Security Act) cannot possibly endear the local emotion or bridge the topical “distance” with Delhi.

Even though Sonam’s wife repeated, “We are with India and the truth and whoever allies with it,” Delhi's unreciprocated reaction is rife with portents.

India simply cannot afford alienating yet another border region and its simple people—especially those who have stood resolutely, proudly, and patriotically through the ravages of multiple wars with the contiguous regions held by Pakistan and China.

Proposed talks between the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) officials with representatives from Ladakh have now been called off too, with the Leh Apex Body (LAB) and the Kargil Democratic Alliance (KDA) saying that “talks cannot be held at gunpoint.”

Just about five years back, during the violent Indo-China standoff, Sonam Wangchuk and his band of Ladakhis had led the chorus of boycotting Chinese wares and upholding the Tiranga. But his recent protest—to ask Delhi to keep its promises made—has led to a now familiar barrage of insinuations and blame-game that goes as far as “Pakistani hand” or “Chinese hand.”

Sadly, majoritarian politics has a way of suddenly dispensing the “other” (never mind their patriotic past) and rationalising strong-arm tactics as a legitimate and nationalistic move.

That it alienates a strategic region given to ethnic or religious minority is regrettably calculated as a small price to pay in the short term as this region only affords one seat in the Lok Sabha, in a house of 543 seats.

The electoral stakes are simply not enough to resist the temptation of “muscular” governance, which galvanises the mood in other parts of the country. It is a pattern seen before—and there are enough pointers to suggest a more engaging and restorative approach may have avoided ensuing tension, but the question is, could Delhi have overcome its own natural instinct?

A Call to Remember Khusrau’s India

It is unsurprising that a mystic, pluralistic, and inclusive poet like Khusrau would no longer find favour in the majoritarian heartland of India or even in Kashmir, for he would either be considered an “other” or a “kufr” (non-adherent), respectively.

His beautiful lines “Har qawmi zaban-e khud o man zaban-e hameh” (Each community has its own language, but I speak the language of all) is unfashionably inclusive and too secular, for today’s liking. The situation in Ladakh ought to concern all right-thinking patriots and democrats as the neighbours would be reveling in yet another potential self-goal by Delhi.

Ladakh, and its historically patriotic Ladakhis, deserve better.

(The author is a former Lt Governor of Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Puducherry. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)