It is deeply troubling to see violence and unrest rip through the Ladakh region, which has always been strongly committed to the Indian Union. Indeed, a poll in an international survey had found, over around a quarter-century ago, that Muslim-dominated Kargil was the most pro-India part of the entire erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.

That should have been cherished, and used as an example to build bridges of understanding and cooperation across the various parts of the erstwhile state. The Autonomous Hill Development Councils, which had worked very well in both the Leh and Kargil districts, should have been further empowered and assisted.

Establishing a lieutenant-governor’s secretariat in Ladakh instead was bound to weaken the Development Councils, after those democratically elected bodies had taken root and had proved effective in that challenging and sensitive terrain.

Now, the place has become a hotbed of disappointment and unrest. Curfew has been in place in Leh for four days, and one must hope that lasting peace will be restored. It would be best to try and accommodate the aspirations of the people of this sensitive border area in an inclusive spirit.

One sincerely hopes there will be an amicable breakthrough at the talks slated for 6 October between the Home Ministry and ranking leaders from both Leh and Kargil. Perhaps a jobs programme could be put in place among other steps.

Inexplicable Division of J&K

It is tough to understand the logic of some elements of—and methods adopted for—the constitutional changes with regard to Jammu and Kashmir. But, of all the various things the Centre chose to do on 5 August 2019, perhaps the most dangerous was to divide the erstwhile state into two.

It thereby junked the state’s constitution, which unambiguously stated that Jammu and Kashmir “is and shall remain an integral part of India.” All the members of the state’s constituent assembly had signed on to that.

But that constitution also stipulated that the borders of the state as ruled by the maharaja could not be changed.

At one level, the separation of Ladakh could be viewed as a needless invitation to China, seemingly driven by political naivete and geopolitical blindness. Indeed, China promptly joined Pakistan to hotly take up the matter at the UN Security Council, reviving it there after decades. And Chinese troops invaded the edges of Ladakh seven months after.

The more predictable result of that change was that, instead of jousting with the state government, Ladakhis would henceforth take up their demands directly, and only, with New Delhi. That indeed happened.

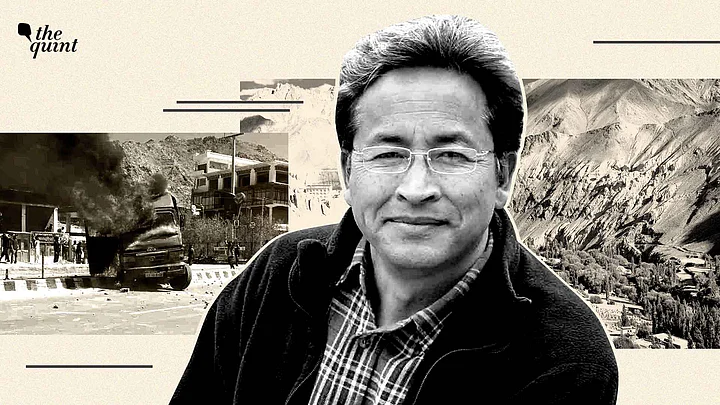

Educationist-environmentalist-activist Sonam Wangchuk, who has been given many international awards, emerged as a voice and symbol for Ladakhi aspirations, but was arrested on Friday under the provisions of the National Security Act.

Wangchuk has been pressing for the application of the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution to Ladakh, which would give Autonomous Councils there the right to legislate on certain matters, including resources—as is the case in four northeastern states.

I wish the government had included Wangchuk in talks instead of imposing the draconian National Security Act on him, which makes it very difficult for him to even get bail. One should appreciate the fact that he ended the latest in his series of hunger strikes (this one had been underway for a fortnight) when the agitation turned violent.

One should note further that, in recent years, he has couched his pleas for Ladakhi autonomy in fulsome praise for, and faith in, Prime Minister Modi.

The art of politics involves engaging in talks.

At the least, they can bring down temperatures—and bring activists off the streets. Talks should be a political option even if—and especially if—one thinks an agitation is backed by inimical powers. Those powers could be marginalised by drawing one’s citizens around a table for talks.

Wangchuk’s Record of Struggle

Wangchuk has a long record of struggle, and suppression, while attempting to make change. Around the time when the demand for separate union territory status for Ladakh was relatively new (the late 1980s), he and several other college students established the Students' Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL).

They revolutionised primary school education at the grassroots in the Leh region over the next decade, establishing committees of parents at the village level to oversee government schools. Government teachers, not to speak of bureaucrats, were so incensed that Wangchuk had to flee Ladakh to avoid possible criminal action.

However, he has never been easy to suppress. He was back a few years later, now an international celebrity focused as much on the environment as on education.

Perilous Perimetres

It is sad to see Ladakh on the edge of rebellious violence, directed at the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a party which many Ladakhis had come to view as a channel of their hopes—before disappointment turned to bitter anger.

The BJP had a great opportunity to undo the corruption and apathy of past governments when people turned to it in many border areas, even in the northeast. It could have realised the aspiration for national security and stability, especially around the borders.

Keeping in view the inimical international scenario, the government must go out of its way to ensure cohesive inclusion in areas like Ladakh. A cooling balm is the need of the hour.

(The writer is the author of ‘The Story of Kashmir’ and ‘The Generation of Rage in Kashmir’. He can be reached at @david_devadas. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)