Seeing Pakistan in a negative light, and often with presumed bad faith, has become second nature to many of us in India. To be fair to the Indian psyche, this instinct is the product of three-quarters of a century of lived and inherited experience. There is no doubt that such presumptions arise from a hardened mistrust accumulated over generations.

Yet it would, and should, contradict the Indian spirit to assume that a Pakistani is, merely by virtue of his or her nationality, a bad person. We conflate, far too often, a place and its political tendencies with the morals of its people. There are men, women, and children on both sides of the border who, if given a real choice, would choose peace over war, principles over perversion, and ideals over opportunism.

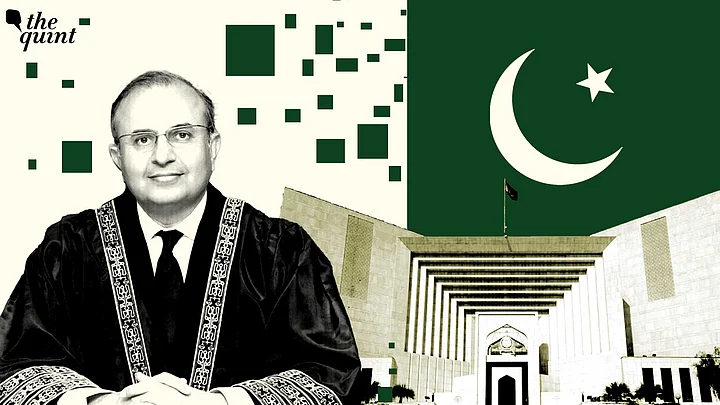

This piece is an ode to one such man—who today stands as a beacon of hope for those in Pakistan who continue to care for progressive values, for justice, and for a government of laws rather than one of kings.

A Jurist, Not a Nationality

At the outset, I must clarify that I know far too little about Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, the private individual. I do not claim to understand his personal life, his opinions outside court, his virtues, or his failings. I write not about Syed Mansoor, but about Justice Syed Mansoor — a jurist whose public identity is derived from his judgments and distilled from the values he articulated on the Bench.

Justice SMASH, as he is affectionately known, resigned from the Supreme Court of Pakistan on 13 November. His resignation followed the passage of the Twenty-Seventh Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan, approved by an overwhelming 234 votes to 4, which grants sweeping powers to the country’s Army Chief, Field Marshal Asim Munir.

Among other things, it demotes Pakistan’s Supreme Court, the constitutional sentinel, to what Justice SMASH described as a mere appellate court stripped of its power of judicial review. His resignation on the very same day comes as a principled repudiation against this legislative dilapidation of what remained as a semblance of constitutional order in Pakistan.

Indian legal education makes little effort to expose lawyers to comparative jurisprudence. At best, it glances at a few familiar common-law jurisdictions and, inevitably, the United States. What remains largely absent is any attempt to look towards Pakistan — a country that inherited a near-identical body of colonial legal instruments as we did.

Entrenched in this inherited indifference, I opened Abreem Akram v. Assad Ullah Khan, a judgment of the Supreme Court of Pakistan that I came across by sheer chance. With an internal, almost involuntary condescension, I must admit. Being a judgement on maintenance law, I assumed, this would only confirm my ill-educated priors: the usual cocktail of belittlement and contempt. Yet what awaited within was a judgement with quality indicative of a humbling intellect.

A Culture of Rigor, Gratitude, and Gender Justice

At the outset, the case credited the amici curiae — both domestic and foreign practitioners of law who had studied the particular question of Islamic law deeply. Even more surprising was a sincere note of gratitude, on the cover page, extended to the young law researchers who assisted Justice Syed J SMASH in crafting the opinion.

The judgement itself was structured in neat sections, with crisply framed questions, extensive footnotes, succinct answers, and a thorough engagement with arguments from both sides. Its conclusion drew these strands together in a manner that would make any jurist envious of the discipline, lucidity, and craft on display.

Justice SMASH appended a sternly worded paragraph admonishing the lower judiciary for its patriarchal reasoning and directing it to adopt gender-sensitive language: “[Judges] bear a constitutional and ethical duty to adopt gender sensitive, rights-based language that affirms equal legal status of women as full and autonomous persons. Judicial decisions must avoid stereotypes, promote tolerance and embody the principles of substantive justice.”

My scepticism and my ingrained disdain for the “other side” of the Indus struggled to stomach this. Surely this had to be an outlier, whispered the pseudo-statistician within me. So I checked. And, to my absolute surprise, I found that Justice SMASH’s judgments were, almost without exception, a delight to read — at least the ones I could locate.

Barely two months before Abreem Akram, in Federal Public Service Commission v. Dr Shumalia Naeem, he held that a married woman “retains the legal discretion, choice, or agency to either adopt her husband’s domicile or retain her own.” The judgment traversed English common-law history, compared the doctrine with Dutch law, and was, yet again, thoroughly researched and meticulously cited.

If that still does not impress, one must go further down the rabbit hole of Dr Muhammad Asif v Dr Sana Sattar and Ors. on the rights of a child, or the District and Sessions Judge (Authority), Jhang v Ghulam Shabbir on the constitutional sanctity of proportionality; the District Education Officer (Female), Charsadda & Ors v Sonia Begum & Ors on the necessity to impose costs to deter frivolous claims in court and manage pendency, and Mohammad Din v Province of Punjab through Secretary, Population Welfare, Lahore where he expounds on protection of women from workplace harassment.

Judicial Activism and Personal Crusades

Over the past few days, Justice SMASH’s voice of dissent has only grown louder within Pakistan’s upper judiciary. Hanging his robes alongside him was his brother judge and former partner in practice, Justice Athar Minallah.

To his own credit, Justice Minallah has an enviable streak of judgments upholding civil liberties in the face of State excesses and using law to undercut efforts to stifle democratic dissent. Justice Shams Mirza of the Lahore High Court stepped down soon after.

The constitutional theatre now presents two stark extremes: on one hand, challenges to the Twenty-Seventh Amendment are piling up before the High Courts of Pakistan; on the other, judges are being sworn into the newly created Federal Constitutional Court.

Opinions will naturally diverge on what the right course for the Republic of Pakistan ought to be. I do not intend to comment on that. But in a world where the rule of law and civilian-led government remain the best democratic technologies humankind has devised — notwithstanding their innumerable imperfections — these judges and their acts of courage will only resound louder with each passing day.

The Basic Structure Gap in Pakistan’s Constitutional Order

Unlike Indian constitutional jurisprudence, Pakistan’s constitutional law does not contain a mature Basic Structure Doctrine that operates as a binding constraint on Parliament. This theory of implied restriction, though initially hinted at in Asma Jillani v The Government of Punjab was soon rejected in the State v Zia ul Rehman opinion.

The apex court declined to treat the Objectives Resolution as a supra-constitutional instrument capable of limiting constitutional amendments. A faint trace of the doctrine resurfaced in Pakistan Lawyers Forum v Federation of Pakistan, where the Court recognised that the Constitution does have a basic structure, but stressed that it is to be defended not by the judiciary, but by the “body politic”, the people of Pakistan themselves. A 2015 judgment swung the pendulum yet again.

In any case, this to and fro has not attained sufficient clarity or maturity enough, as would have prevented the 27th Amendment from happening. It is now law. Dejected, Justice SMASH has left the court. For an Indian reader familiar with the enduring legacy of Justice HR Khanna, the resonance is immediate.

At a moment in time when perverse power permeates all around oneself, speaking truth is, by itself, admirable. To step away from the scraps of power, pitifully left as alms by those who usurp the sceptre, is courage of the highest order.

Such courage is profoundly human and is part of what makes the dream of a land ruled by law a shimmering ideal that may be still far away, yet definitely worth its painful pursuit. It belongs equally to men, women and others, on both sides of the Indus.

(Statement of Gratitude: Pakistan’s Supreme Court website is not directly accessible from India. I stumbled upon Justice SMASH’s judgments through the profile of Mr Omar A Ranjha, a former judicial clerk to the Justice and a lawyer by training. I am grateful to him for making these judgments publicly accessible in full.)

Attached here under are a few selected paragraphs, from Justice Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah's resignation letter:

The Twenty-Seventh Constitutional Amendment stands as a grave assault on the Constitution of Pakistan. It dismantles the Supreme Court of Pakistan, subjugates the judiciary to executive control, and strikes at the very heart of our constitutional democracy – making justice more distant, more fragile, and more vulnerable to power. By fracturing the unity of the nation’s apex court, it has crippled judicial independence and integrity, pushing the country back by decades.

As history bears witness, such a disfigurement of the constitutional order is unsustainable and will, in time, be reversed – but not before leaving deep institutional scars. At this critical juncture, only two courses are open to me as a Judge of this Court: either to remain within an arrangement that undermines the very foundation of the institution one has sworn to protect, or to step aside in protest against its subjugation. Staying on would not only amount to silent acquiescence in constitutional wrong, but would also mean continuing to sit in a court whose constitutional voice has been muted. Unlike the Twenty-Sixth Amendment – when the Supreme Court of Pakistan still retained the jurisdiction to examine and answer the constitutional questions – the present amendment has stripped this Court of that fundamental and critical jurisdiction and authority. Serving in such a truncated and diminished court, I cannot protect the Constitution, nor can I even judicially examine the amendment that has disfigured it.

I am unable to uphold my oath sitting inside a court that has been deprived of its constitutional role; resignation therefore becomes the only honest and effective expression of honouring my oath. Continuing in such a version of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, would only suggest that I bartered my oath for titles, salaries, or privileges. Accordingly, for the reasons set out hereunder, and in terms of Article 206(1) of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, I hereby resign from the office of Judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, with immediate effect.

(Gokul K. Sunoj is a lawyer and legal researcher. His work focuses on legal systems, court performance, and strengthening the rule of law. This is an opinion piece. All views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)