A recent interview by former Chief Justice of India, DY Chandrachud, has brought back into spotlight the serious lack of diversity within the justice system, particularly the higher judiciary, and that it is dominated by elite Hindu upper caste men.

The judiciary is the chief custodian of the Constitution, but itself falls short of achieving the constitutional goal of equality. And so does the justice system as a whole.

As of January 2025, the average share of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe judges in lower judiciary is 19 percent. According to a recent answer in the Parliament, out of the nearly 700 judges appointed to High Courts since 2018, 15 belong to Scheduled Tribes, and 22 to Scheduled Castes. The representation of women is growing but at a languorous pace.

Beyond Numbers and Statistics

Concerns on the abysmal status of diversity are often sought to be assuaged by the ‘promising’ rise in the number of female judges in the district judiciary. This rise, last reported more than two years ago (December 2022) in a parliamentary answer, revealed that nationally 35 percent of the judicial officers in district courts were female.

As statistics often do, this average 35 percent share of women judges conceals the wide disparity across states.

In states like Uttar Pradesh (32 percent), Bihar, (24 percent), and Gujarat (19 percent), women judges are well below the halfway mark. It is in smaller states like Goa, Manipur, Mizoram, Sikkim and others that women judges’ share is more than 50 percent.

The situation is even more dire in the higher courts, where appointments are made via the collegium system that recommends names for elevation of judges from the lower courts or directly from the bar.

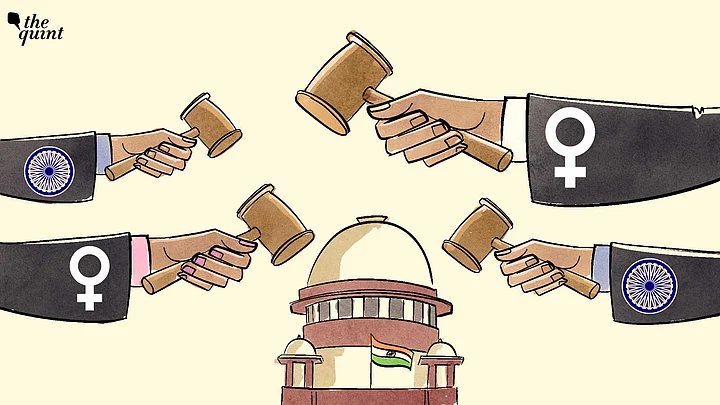

As of today, only 13 percent of High Court judges are women with only the Gujarat High Cour having a serving woman Chief Justice. Over 75 years since Independence, the Supreme Court has only had 11 female judges and not a single female Chief Justice. The first female CJI would be appointed in 2027, for a period of 36 days before she retires. Currently, out of 32 judges, there are only two females at the Supreme Court.

The collegium recommendations throw light on the lack of diversity in the recommended names themselves. In the two-year period between 2022 and 2024, out of 17 recommendations made for appointment to the Supreme Court, not a single female was recommended, and out of 168 judges being recommended for the High Court, only 27 were women.

The diminishing presence of female judges as we go up the ladder signifies a leaky pipeline and the glass ceiling — both attributable to systemic barriers and gender bias that women face in a profession that has historically been male dominant.

The exiguities of women in the higher echelons is often attributed to the inadequate pool of senior female judges and lawyers. Typifying patriarchy, women lawyers have been castigated for allegedly refusing judgeship citing domestic responsibilities. Such arguments betray deep-rooted discrimination against women who must jump through hoops of perception, opinion and judgement to prove themselves before laying claim to a place in the higher echelons.

The Making of a Diverse System

The same paradigm holds true for the police, the first interface between the people and the justice system. Across the country, there are too few women in the police, particularly among officer ranks. As of January 2023, nationally, the overall representation of women stood at only 12.3 percent. At the officer level, their share falls to just 8 percent. The performance of states in meeting their respective caste quotas belies the political rhetoric; Karnataka is the only state that has consistently met its SC/ST/OBC quotas in the police.

Making any system more diverse requires a structural response to the needs of diverse populations. For instance, in courts, diversity cannot increase with just a simplistic increase in the number of female law students and ultimately female lawyers and judges.

In fact, evidence suggests that over the last decade, the proportion of females in law schools has hardly increased from 32 percent to just 33 percent and female advocates account for a mere 15 percent of the total strength. The growth, thus, can never be imagined to be so linear.

In 2016, the 7th National Conference on Women in Police also noted how women police personnel continue to grapple with lack of basic amenities like toilets, uncomfortable duty gear, and want of privacy. In 2023, the State of the Judiciary report of the Supreme Court revealed that around 20 percent district courts do not have washrooms for females — and many that do have are also unhygienic and practically unusable.

A framework where right from the architecture to age limits in recruitment rules, transfers, and everything in between has been formulated around a normative understanding, the system whether it be the judiciary or the police, is bound to reflect it. Until there is a stronger institutional will and a cultural transformation, the promise of equality will remain just that.

(Valay Singh is Lead, India Justice Report. Sarab Lamba is a Research Associate, India Justice Report. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)