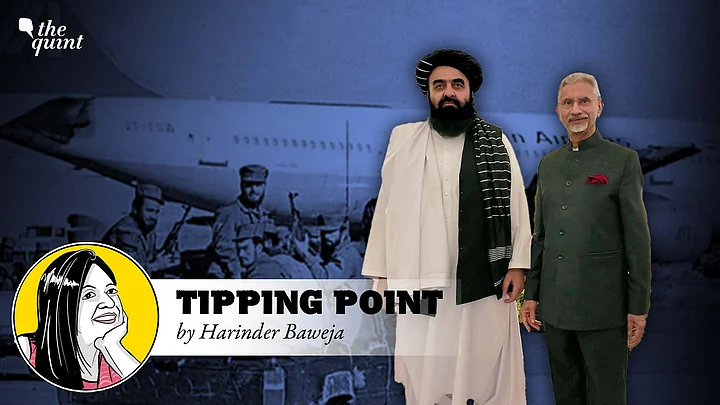

History often comes with forceful reminders. When the Taliban Foreign Minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, landed on Indian soil, for some it was a reminder of how the turbaned army had helped the hijackers of flight IC 814.

The wife of an Indian foreign service officer—who was killed in a horrific suicide bombing attack on the Indian embassy in Kabul in 2008—told The Quint that the sight of Muttaqi made her feel like she was nothing but a "pawn on a political, geo-strategic chessboard."

The irony of the Muttaqi visit is inescapable. To use the oft-voiced cliché, it is a reminder that there are no permanent enemies or friends, only permanent interests.

Here are some harsh truths: Muttaqi is on the sanctions list of the UN Security Council. The UN does not recognise the Taliban to be the rulers of Afghanistan, but was willing to give the foreign minister a travel waiver.

From Kandahar to Kabul

More ironies: the same Taliban that kept a watchful eye on the hijacked flight in 1999, were the ones that escorted Maulana Masood Azhar as soon as he landed in Kandahar, as part of an exchange deal that secured the safety of the passengers on board IC 814.

Azhar launched the Jaish-e-Mohammad soon after and became the father of suicidal bombing. His ‘army of the faithful’ has its eyes firmly set on India since then. And now, Muttaqi is being welcomed on Indian soil, a few months after Operation Sindoor. The Taliban has close links to the Lashkar-e-Taiba, which was rechristened as The Resistance Front. It is the very group that shot tourists at close range in Pahalgam on 22 April.

As I watched Muttaqi being feted by India, which officially still doesn’t recognise the Taliban to be the rulers of Afghanistan, I was reminded of my own tryst with the turbaned army. I was in Kabul for two weeks after they first took control of Afghanistan in 1996. They ruled through the force of the gun and through an extreme interpretation of the Quran, which allowed public executions of Afghans who didn’t pray five times a day or didn’t show up at mosques.

Women Behind Walls

The women—comprising fifty percent of Afghanistan’s population—were ordered indoors in 1996 and the same is true since 2021, when the Taliban strode back to power for the second time.

I got a good taste of how the Taliban treats women. The memory is etched in my head, for it is a powerful one. The then deputy foreign minister, Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai, was the only high-ranking Talib who deigned to speak to me in his office, on the condition that I would not look him in the eye.

That was a difficult ask. I believe in making eye contact, an essential tool, that helps ease the equation between the interviewer and the interviewee. The Stanekzai interview was the only ever interview I did while staring at a wall, as I’ve written in my recent book.

The edicts for women are far worse now than they were in 1996. The world capitals, New Delhi included, appear willing to sidestep the crucial fact that women are now not even allowed to pray loudly within their new homes. The Taliban, of who Muttaqi is an important part, has ordered new homes to be constructed without windows, so men don’t accidentally glance at women.

Afghanistan will soon be a country without female teachers, nurses, and doctors. They have been banned from seeking education and from being trained to even work in hospitals.

Why India Is Engaging With the Taliban Again

So why has India gradually upped its engagement with the Taliban, the very force it had initially shut its doors to in 1996 and in 2021?

The answer lies in the fact that India had lost a large part of its influence in Afghanistan after the Taliban's return to power in 2021. The advent of the Taliban had reversed two decades of gains India had made through diplomacy that focussed on development and strong people-to-people policies.

If India is willing to keep the door half open now, it is because the Taliban is no longer under the grip of Pakistan and its deep state, which helped train and arm it. The regional order is shifting and the Taliban’s relationship with its mentor, Pakistan, is more than just shaky. India sees this as an opportunity for what strategic experts call ‘cautious diplomacy’.

India is looking at stepping in—and stepping up—at a time when the Taliban and China are appointing high commissioners in each other’s countries. For the past few years, since the stand-off with China, India has had to face a threat on two important borders: the line of control with Pakistan and the line of actual control with China. India wants to seize some control over its rivals, but cosying up to the Taliban is fraught with risk.

The red-carpet treatment for a militia—that is unwilling to give up on its connections with terror groups like the Al-Qaeda—also come in the backdrop of US President Donald Trump’s punitive trade tariffs and his open-arm welcome of Pakistan Army Chief, General Asim Munir, in the aftermath of Operation Sindoor. Afghanistan was amongst the countries that condemned the Pahalgam attack.

New Delhi’s Tightrope Walk

Changing geopolitical landscapes often open doors and windows but New Delhi would do well to never forget that Muttawakil, who they are now feting, is a proscribed gun-wielder. Another colleague, Sirajuddin Haqqani, Afghanistan’s interior minister—also a proscribed terrorist—was the one responsible for the suicide bombing in 2008.

The Taliban is desperate for world recognition. India needs to weigh its options with a high degree of caution. As it tries to posit itself as a regional architect, it must never forget that in January this year, the International Criminal Court issued warrants against Taliban supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada on charges of gender-based persecution.

In the end, New Delhi has more to lose. The Taliban—which refuses to mend its medieval mindset—will only gain. The gain started the minute it received an invitation from the Indian government. It, in fact, has nothing to lose.

(Harinder Baweja is a senior journalist and author. She has been reporting on current affairs, with a particular emphasis on conflict, for the last four decades. She can be reached at @shammybaweja on Instagram and X. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)