Friction between gig economy workers and the platforms they engage with is not new anymore. By now, in 2026, there has been a pattern of struggle and back-and-forth on the matter. There continues to be a steady stream of discourse which centres the vulnerability of the gig workers, their precarity and low earning potential compared to the kind of labour they put in.

Such issues and related regulatory debates have also been subject to legislative discussion and policy, both at state and national levels. Hence, it was not unexpected that organised labour action would follow at a mass level on this issue.

On 25 December, a nationwide strike by platform-based gig workers began. Led by the Gig and Platform Services Workers Union (GIPSWU), the call for action expanded rapidly with multiple organisations representing gig workers’ rights joining in. The strike was extended till 31 December 2025, coinciding with one of the busiest periods for delivery-based services. This was meant to hit the companies hard during their busiest revenue spinning period.

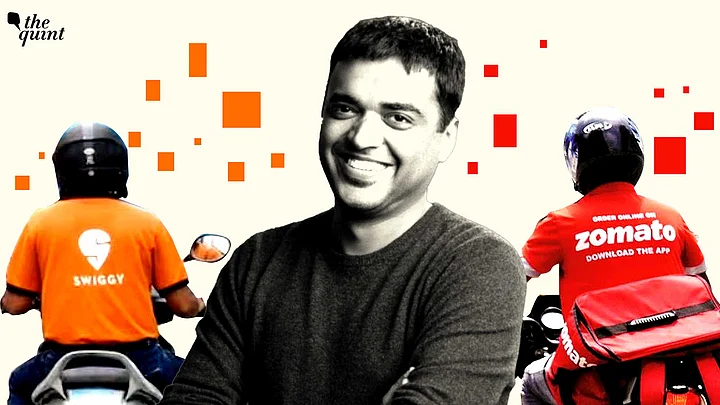

As the strike gathered momentum, social media commentary exploded. Critical commentators with big followings such as Kunal Kamra jumped in on the issue, putting direct pressure upon these companies. This led to a pushback by the companies, championed by Deepinder Goyal, the head of Zomato and Blinkit (originally Grofers, acquired by Goyal in 2022 and rebranded as Blinkit).

Reframing Labour as Elite Guilt

In a long post on X, Goyal explained his worldview with regards to the matter. In a reframing of the argument from an economic/labour bargaining dimension, to one debating social standpoint and guilt, Goyal tried to flip the argument back on his most vocal critics online.

He historicised labour and consumption, and correctly in one’s opinion to some extent, suggested that the consuming class was always shielded from the ones who toiled for its comfort. This distance is what he claims the gig work platforms have broken down. The one who orders (primarily food and grocery items in the case of Goyal’s companies) is forced to see the person delivering.

Often the delivery is a casual, impulse decision made while the delivery-person has braved harsh weather, traffic, and odd hours to get there. The moment and its contrast can be jarring. This is not wrong.

Goyal calls this an emotional reckoning and assumes the guilt it forces upon the receiver is what is being thrown back at the likes of him and the gig work ecosystem. He says ending or over-regulating gig work would not solve this jarring experience, it would just take away jobs and build back the distance which makes the consuming class ‘guilt-free’.

Erasing Workers, Centre-Stage Consumers

From his narrative, it would appear Goyal locates the upper class/upper caste elite guilt as a primary motivation behind the protests. This is strange since the social media outrage is a product of gig workers mobilising efforts which precede—and one could argue are fairly independent of—social media critiques which emerged later.

Goyal and ilk seem more focussed on their consumers’ tweets than their workers' issues. In this Goyal is not unique, it is a very savarna tendency to take labour for granted, so much so that it can be invisibilised and brushed off as a sideshow or a minor, unavoidable inconvenience.

He reduces the gig workers’ resilience and agency in organising at big risk as merely animated by elite guilt. The worker becomes just a vessel in this moral conflict centred around the guilt of the platform users and the ‘heroic struggle’ that Goyal sees himself part of.

The Savarna Tech-Bro Mythology

This sense of heroism is endemic within the unique savarna millennial tech/MBA ecosystem, which emerged as India Inc’s most visible business success stories around the 2010s.

Having read one too many puff pieces about their daring innovation and disruption, this class of mostly Bania adjacent savarna entrepreneurs have ended believing their own myth.

They are not just heads of profitable companies, they also see themselves as leading a charge against an archaic Indian ‘mindset’. They are the heralds of capitalism, the torchbearers of progress, the rockstars who are transforming India– one startup at a time. And because of this they are also targeted and hounded by ‘negative’ forces, something they must buckle down and fight like the ‘lionhearted warriors’ they are.

Hence, it was not a surprise that Goyal was cheered on by multiple entrepreneurship/startup influencers and their followers. Kunal Shah, founder of CRED, took to X and urged “all popular Indian podcasters” to debate the merits of capitalism. This bizarre internal self-validating and deeply flawed way of thinking, where every voice which is not appeasing or millionaire-founder adjacent, as illegitimate and without any merit to speak on the matter, would have been incredibly funny had it not had such structural implications.

What it shows is that India’s gig platform leaders and tech-entrepreneurs at large are too one dimensional and unimaginative to even process the problem. Gig economy jobs are not the solution that India’s labor market needs. It is at best a stop-gap. A vast underclass of under-employed youth may see these jobs as a pit stop in their twenties, but this is not a line of work that most of them can make a whole lifetime of living out of.

If Goyal and his kind felt otherwise, they would strongly consider extending to gig workers more of the workplace-securities and stable policies that they are asking for. A gig worker is still a worker who is still a person, who has to be treated as such until a robotics revolution arrives from overseas (it is definitely not happening in India given the dismal record of its supposedly ‘innovative’ techpreneurs).

Charity Instead of Rights

Instead, it is clear from the responses of this cohort and their supporters that they have completely misread the room. In their head, they should be celebrated but are instead criticised by people without the ‘talent or hard work ethic’ and so inherently, they end up framing every critique as a tantrum.

“What have you built that you are criticising Zomato?” is a typical response from their supporters. Validated by the appeasing cult following many of these fragile-egoed man-children desire so badly, they are likely to focus on incentivising and finding ways to wean away striking gig workers, instead of trying to create a business model that takes care of all its stakeholders in a sustainable way.

And as a final cunning thrust, they will shift the onus to the consumers to “tip” the delivery person if they are so worried about the gig worker. Individual charity over structural security is typical of savarna-welfarism. It is the traditional model of caste. Our ‘techbros’ have leaned on the classical, so I guess they are not so innovative after all.

(Ravikant Kisana is a professor of Cultural Studies and author of the book 'Meet the Savarnas'. He can be contacted on X/Instagram as 'Buffalo Intellectual'.The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not reflect or represent his institution.This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)