The year 2025 has brought two major setbacks for public transport users in Bengaluru, a 15 percent fare hike by the Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC) from 5 January and a 71 percent fare increase for Namma Metro, operated by the Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Limited (BMRCL), from 14 February. The commuters raised concern over increasing expenses on their essential modes of transport and mobility experts raised concerns over possible shift in mobility behaviour.

Shift to Private Vehicles

The price hikes in public transportation systems disproportionately affect the lower and middle-class populations, who together make up approximately 54 percent of Bengaluru’s population. People under these categories work as domestic workers, security guards, small-scale shopkeepers, food vendors, construction workers, delivery agents, and the like. The increased costs may force many commuters to seek alternative modes of transportation.

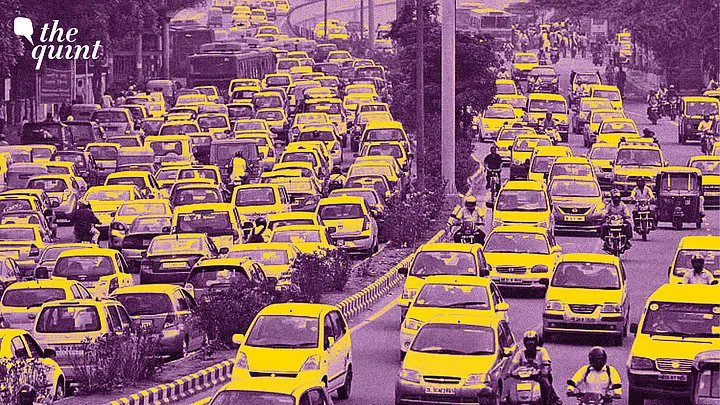

With rising public transport costs, many may turn to private vehicles, worsening an already pressing traffic issue. The stark difference between private vehicle registration and BMTC buses is a major concern.

With 10.21 million private vehicles (including only two-wheelers and cars) vastly outnumbering the 6,340 BMTC buses, this poses two significant challenges: the current bus fleet is inadequate for effective last-mile connectivity, and the surge in private vehicles leads to increased traffic congestion.The price hike in public transportation systems is detrimental to solving the city’s traffic woes as commuters may seek alternative modes of transportation, such as two-wheelers, bicycles, and cars.

Misplaced Priorities

Adding to the already mistaken step of rising fare prices of public transportation systems, the Karnataka government announced an allocation of slightly above Rs 1 lakh crore towards large-scale projects to ease the city’s traffic woes. This includes a 40-km-long twin tunnel (costs Rs 42,500 crore), a 41km double-decker corridor by integrating road and Metro rail (Rs 18,000 crore), a 110 km elevated corridor (Rs 15,000 crore), buffer roads (Rs 5,000 crores), a sky deck (Rs 500 crore), and a 74 km Bengaluru Business Corridor (Rs 27,000 crore).

Road expansion-based large-scale projects pose two major issues. Firstly, the simultaneous execution of such large-scale projects would lead to higher traffic as multiple streams of traffic would be forced to pass through one single stretch. In addition, delays in completion would worsen the situation. For example, the pending 58.19 km Blue Line that connects the airport to the existing Metro rail, the Hebbal flyover expansion, etc.

Secondly, the assumption that more roads would lead to unclogging of streets is flawed, because building more roads will lead to ‘induced traffic’.

There is no end to examples, for instance, the testimony to this argument are Tokyo, London, Jakarta, Bogota, and Los Angeles, among others. These projects highlight the government's misconceived notions of city planning. It is aiming to build cities for cars and traffic when they should be built for people and places instead.

Cities designed for people prioritise robust public transportation systems, ensuring accessibility, efficiency, and sustainability.

Public Transport System: Bogota

While Bengaluru struggles with traffic congestion, Bogota, a city shares similar demographics, has successfully tacked this issue by prioritising public transport. It has a population density of 4,310 people per square km (it's 4,370 per square km for Bengaluru), it is the economic hub of Columbia with high manufacturing industries (like the IT sector in Bengaluru), and both these cities are home to a large informal workforce. The stark difference lies in their approach to solving traffic congestion.

Bogota is a two-time recipient of the ‘Sustainable Transport Award’, in both 2005 and 2022. Its robust public transportation system prioritises people and places over building more roads. Bogotá’s public transport system comprises a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, feeder buses, and zonal buses, each serving distinct roles.

The BRT buses, known as TransMilenio include high-capacity articulated buses which operate on dedicated lanes for faster and efficient travel along major corridors of the city. Feeder buses connect TransMilenio bus stations to residential areas, ensuring first- and last-mile connectivity without dedicated lanes. Zonal buses function like a conventional bus network with standardised fares and routes.

This robust system working alongside other measures to solve traffic congestion is showing results.

As per the TomTom Traffic Index, which measures the average time taken to travel 10 km, Bogota was ranked third in 2021 and is ranked 40th in 2025. This is proof that solving traffic congestion by improving the public transportation system really works.

Along the same lines, Bengaluru is expected to receive 7,000 e-buses in the next three years under the PM E-Drive scheme. This may well be the need of the hour. A meticulously planned route map and dedicated lanes along major corridors with stronger enforcement are, nevertheless, prerequisites when the government of Karnataka acquires these buses. This move has a dual effect; electrification of public transport, and a higher possibility of first- and last-mile connectivity.

Solving traffic congestion is a long-term challenge that demands strong government commitment. On the spectrum of urban mobility evolution, Bengaluru’s car-centric approach remains in its infancy, while Bogotá’s public transport-first strategy has reached a more advanced stage, demonstrating the effectiveness of prioritising sustainable transit solutions.

Commuter behavior will change only with frequent buses and better first- and last-mile connectivity – a recent study byIndian Institute of Science (IISc) showed that 60 percent are willing to shift to public transport if buses are improved to meet their needs. Bengaluru needs to implement a people-first urban mobility model rather than perpetuating a cycle of congestion and inefficiency through road expansion.

(Ganesh R Kulkarni is a Political Science and Economics student at MAHE-Blr. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)