The controversy around The Bengal Files isn’t really about cinema. It is about memory. Critics say the film distorts history. But the real unease perhaps lies deeper: it revives truths Bengal has chosen to forget.

George Santayana warned: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Bengal’s silence over 1946 proves his point. Forgetting may feel safer, but it leaves wounds unhealed and dangers unacknowledged.

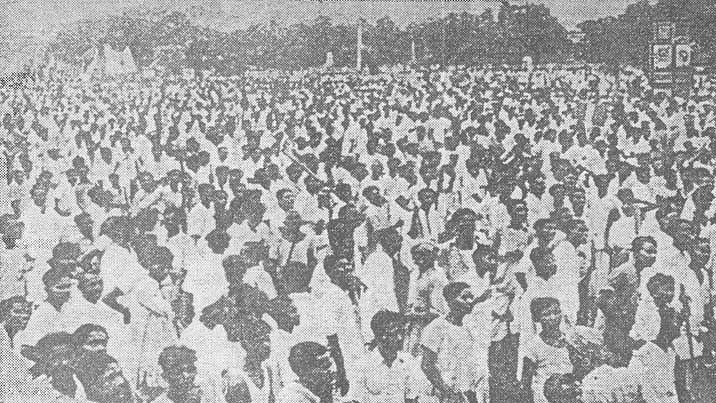

Noakhali: Gandhi as Witness

The “Great Calcutta Killings” of August 1946 weren’t merely class uprisings or caste feuds. They were essentially communal riots. The Statesman wrote on 17 August 1946: “The killings were on communal lines; mobs identified victims by religion before the sword fell.”

Governor Sir Frederick Burrows called it “communal rioting of a ferocity unparalleled in Calcutta’s recent history.”

Men were dragged off trams, forced to prove their faith by reciting prayers or baring their bodies. While spatial sociopolitics may give a background to understanding the complex matrix of the violence, on the ground during the 'Week of the Long Knives', caste and class matrix did not matter as much. It was mainly religion that decided who lived and who died.

In October that year, the violence spread east. In Noakhali, a shell shocked and thoroughly shaken Gandhi walked barefoot through the ruins: “I walk through villages that are desolate, with homes burnt, women violated, men killed or driven away. This is not politics; this is savagery," he said.

British reports confirm what survivors knew — this was no peasant revolt. It was communal violence aimed largely at the Hindu community.

Inconvenient Truths and Gopal 'Patha'

Amid the chaos, figures like Gopal “Patha” Mukherjee emerged. In a 25 April 1997 BBC interview with Andrew Whitehead , he admitted arming Hindu men to defend neighbourhoods after the wanton killing and mayhem of Direct Action Day on 16 August 46, starting a spiral of violence that lasted till 21 August in Calcutta when Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was Bengal’s Premier and the state administration failed to protect its Hindu citizenry. His words are inconvenient, but they cannot be erased.

Later reinterpretations overtly recast these events as “peasant struggles” or “class conflict.” Bengal had famine in 1943 and poverty, yes. But in 1946, the slaughter wasn’t about class or food. It was about religion. To deny that is to deny lived testimony.

Unlike Punjab, Bengal buried its scars. Refugee stories were told, but the communal killings before Partition were hushed up.

The price of silence is prolonged trauma, often transgenerational. Suppression isn’t healing; it’s denial.

Truth Is Not Collective Blame

Agnihotri's film references the controversial “30 percent theory,” popularised by Professor Rafael Israeli — the idea that when a minority nears a third of a population, separatist pressures rise.

It is a debated lens, not a universal truth. But it is a perspective and perspectives should be dismissed by debate, not censor.

Indian audiences are mature enough to handle a film on pre-Partition past and sift through truth from fiction. Suppression insults their maturity. And in today’s digital world, suppression only fuels wider circulation.

Recalling 1946 isn’t about blaming Muslims today. No community answers for its ancestors’ sins. Screening The Sabarmati Report — revisiting the 2002 Godhra train burning — didn’t spark violence. Why should this?

Historian Joya Chatterji notes how Bengal’s elite downplayed the 1946’s communal violence, favouring class or secular explanations to prevent retaliation. It may have worked then. But the amnesia was only temporary albeit a few decades long. Memory does come striking back.

Other nations have faced their past: South Africa through a Truth Commission, Germany through Holocaust memorials, Rwanda through open testimony. Bengal chose omission.

Reconciliation built on denial is fragile. Closure requires honesty. The greater danger isn’t remembering too vividly. It’s forgetting too conveniently.

Tagore dreamed of an India “where the mind is without fear and the head is held high… where words come out from the depth of truth.” We can bury our past out of fear or convenience, but then we betray that dream and Our nations collective belief in Satyameva Jayate.

(Manoj Mohanka is a businessman who serves on several corporate boards. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)