For more than three decades, Acharya Satyendra Das conducted worship of Ram Lalla — first at the 'temple' under the central dome of the Babri Masjid, then at the makeshift temple built on the rubble of the mosque after its demolition by a mob on 6 December 1992, and finally at the new temple after the 2019 Supreme Court judgment that awarded the disputed site to Hindu parties, even while admitting that there was no evidence to suggest the existence or destruction of an ancient Ram Temple to erect the mosque.

Das remained an important voice from Ayodhya since he took over from Mahant Lal Das in March 1992. Lal Das, who was an opponent of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), was murdered in 1993.

Who Was Satyendra Das?

Born in a poor family in the neighbouring Basti district, Satyendra Das began his life in Ayodhya under the tutelage of his guru (teacher), Abhiram Das, during the period of great churning around India’s Independence in 1947.

His life would have taken a different, perhaps quieter trajectory, had it not been for Abhiram Das, who became the chief protagonist in the sordid affair of forcibly implanting the Ram Lalla idol inside the 16th-century mosque on the intervening night of 22-23 December 1949.

The idol's implanting was preceded by a nine-day Ramayana recital held at the Babri Masjid. Satyendra Das was a part of the group that met the then District Magistrate of Faizabad, KKK Nair (accused of 'dereliction of duty' leading to the illegal implanting and, by some, of even masterminding the entire effort to capture the mosque ahead of the 1951 Lok Sabha election).

Recounting those days, Das had said, “The sadhus in the meeting were of the opinion that the surreptitious planting of the idol of Rama Lalla would be much better than taking over the mosque through a mass action. Nair gave them the impression that he would provide all the possible help from behind the scenes if they planted the idol stealthily”.

Writing about this particular incident in their book, Ayodhya: The Dark Night, Dhirendra Jha and Krishna Jha write, “This assurance by Nair was crucial, for it changed the entire scenario. The locals as well as the section of vairagis (ascetics) working with them knew they did not have to worry about the consequences, and that the local administration would rather cooperate with them than take stern action against them. It was indeed a promise that Nair and his assistant fulfilled when required, and they did so with deliberation and precision. It was now just a question of finding a person suitable and willing to plant the Ram Lalla idol."

That Night in 1949

Abhiram Das, a burly fellow, took up the job and, along with a few other sadhus, scaled the mosque’s wall, beat up the muezzin, Abul Barkat, and planted the idol. They also wrote some religious graffiti inside the mosque and started singing the bhajan, “Bhaye prakat krupala, Deen dayala Kaushalya hitkari…”. Later, Barkat, fazed by the series of events and the partisan role of Nair, made up a miracle story to cover up his failure in guarding the mosque and also to provide a divine explanation for the appearance of Ram Lalla idol at the place that was alleged to be the exact birthplace of the deity.

Satyendra Das, though not himself involved in the act, was close enough to the protagonists to know what had transpired. He put paid to the miracle theory.

“Abhiram Das and others had taken the idol of Rama Lalla inside the mosque well before 12 o’clock that night when the shift at the gate changed, and Abul Barkat resumed his duty."Acharya Satyendra Das

This tendency to speak plainly and without fear was what marked Das out in Ayodhya, where the pressure to speak in one voice had made everybody fall in line. This is not to say that Das was not pro-Ram temple. That he was, as much as any other sadhu in Ayodhya. But he was against violence and the politicisation of the issue by 'outsiders'. This was an article of faith for him, and he maintained this non-political stance till nearly the very end of his life.

Outsiders' meddling in Ayodhya is something that united the locals of this small, sleepy town.

Speaking about the years preceding the demolition that saw widespread bloodletting, especially in the wake of the rath yatra taken out by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)'s LK Advani, Das had told me in an interview in 2016,

“What could we do? The whole country was talking about us; not only talking, Hindus and Muslims were killing each other in the name of Ayodhya. Nobody wanted to know what we thought."

Politics of Hanumangarhi

Mahant Satyendra Das lived in Shaheed Gali (martyr's lane) in an ashram called Satyadham Mandir, with his extended family. His living quarters were cramped but offered him a level of privacy and convenience. Das’ life followed a fixed pattern. Around 10.30 am every day, he reached the makeshift temple of Ram Lalla. The ritual of offering food to the deity was conducted under his supervision. "It is both a job and an honour for me to take care of Ram Lalla. It is the world’s best job," he told me.

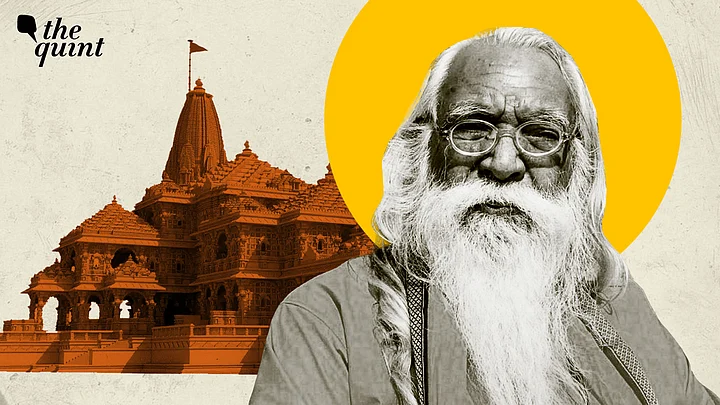

Bespectacled, with a flowing white beard, Satyendra Das was different from the other mahants (priests) in Ayodhya, with his mild manners and soft-spoken demeanour. Ayodhya’s mahants are usually animated and boisterous, but Das, who remained aloof from the colourful street life of Ayodhya, was more inclined towards spirituality. Till the end, he never tired of repeating his stated position — that ‘only the Supreme Court can decide the case, but Ram Lalla will not move from that spot’.

Das, in fact, symbolised the famed Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb (culture) of the erstwhile court of Awadh, specifically the unity of Ayodhya's people. In 2003, when Mahant Gyan Das of the powerful Hanumangarhi temple held an Iftar celebration in the temple's premises, some of the key attendees were Das and Hashim Ansari, the main litigant in the Ram Janmhaoomi dispute till his death in 2016. Satyendra Das also made it a point to greet and wish Muslims on Eid every year.

The day after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, he was quoted as saying, “They have broken our temple, not a mosque. For the last 40 years, Muslims didn’t even visit the mosque. It was a temple, and now Ram Lalla is sitting on the rubble, under the open sky, unprotected from the cold.”

Das had also recounted that the donation box, brass bells, and other items got buried under the debris. "Many of them started breaking the walls in the sanctum sanctorum and I feared for the idol itself, but managed to save it," he had told me.

Hindutva, Elections and Ayodhya

For more than a decade after the demolition, Hindutva politics remained on the fringes. In Uttar Pradesh, the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party remained in power for over 15 years. Meanwhile, the Ayodhya matter languished in courts, as multiple efforts at ‘peaceful resolution’ sprang up and disappeared.

After the massive BJP win in the general election of 2014, I met Satyendra Das. The head priest of the Ram Lalla shrine at the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid site, was not swayed by the BJP’s success. "I have seen so many elections where my Lord Ram has been used as a polling agent by the BJP and other parties. If the temple is built, it will be through the court’s order and not by any government. Of course, the prime minister [Modi] can try to create consensus between Hindus and Muslims, but will he?" Das had noted at the time.

Three years later, in 2017, when the UP Assembly elections were around the corner and all parties were trying to outdo each other in appeasing "Hindu sentiment", the BJP government at the Centre announced the setting up of a new Ramayana Museum. Not to be left behind, the SP government quickly offered to allocate land for it.

When I met him during Diwali in 2017, Das was busy supervising the preparations for the evening puja. While playing with his grandniece, who kept pulling his flowing white beard, Das weighed in on the political announcements and the renewed efforts for a ‘peaceful resolution’ of the dispute. Cradling the child in his arms, he said, "It is nothing more than a lollipop ahead of the elections."

Linking the choice of his metaphor to the presence of the child, I asked him what he thought about the revival of media interest in Ayodhya’s affairs. As the child toddled off, Das put on a serious face and said, “These things always happen, we are used to it; elections, calls for peaceful resolution, media stories, this goes on here. Those who are supporting these so-called 'mutual resolution' schemes know that they will fail but they do it for the free publicity”.

Das may not have been as rich and powerful as the other mahants in Ayodhya. As a government-appointed priest, he had little control over the donations received; he also couldn’t exert any other form of temporal power as the disputed shrine had been claimed by much bigger forces like the RSS and the VHP. However, that didn’t diminish Das’ importance, or his outspokenness.

After the Pulwama attack, which happened a few weeks before the 2019 Lok Sabha election, he gave statements anticipating that PM Modi would now put the Ram Temple issue on the back burner and play up the attack and India’s response to it to improve BJP’s chances. The same strategy played out — and the BJP again came back with a thumping majority.

The Judgment and After

The year 2019 marked a watershed moment for Ayodhya.

After the Supreme Court handed the site to VHP-linked parties, the Central government under Modi set out to make Ayodhya great again. This marked the beginning of the growing irrelevance of Satyendra Das. While the newly formed Ram Janmabhoomi Trust didn’t remove him, it reduced his role in subtler ways, leaving him bitter. However, he didn’t betray his resentment at being sidelined during both the temple’s foundation stone-laying ceremony in 2021 or its inauguration in 2024.

After the BJP lost the Faizabad seat in the last general election and the right-wing troll ecosystem began blaming Ayodhya’s Hindus for it, Das, quipped to me over the phone,

“They are shameless, those who blame us, the people of Ayodhya. Such people only remember Ayodhya and Ram for votes, today Lord Ram whom the BJP used as a polling agent, has shown them his power.”

With Das' death on 12 February, an important chapter of Ram Mandir's history and politics of the movement has ended. In the end, did Das get his due? Did he (and his ilk of sadhus) get the credit for the temple? Did he die content with the Ram Mandir? What would his legacy be?

His life would nevertheless remain a reminder that in Ayodhya, where myth and history intermingle to form an unending tapestry of real and imagined fact, saffron is not an all-encompassing colour but a shade of the multifaceted Hindutva movement that eventually culminated in the construction of Ram's temple.

(Valay Singh is a senior journalist and the author of Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)