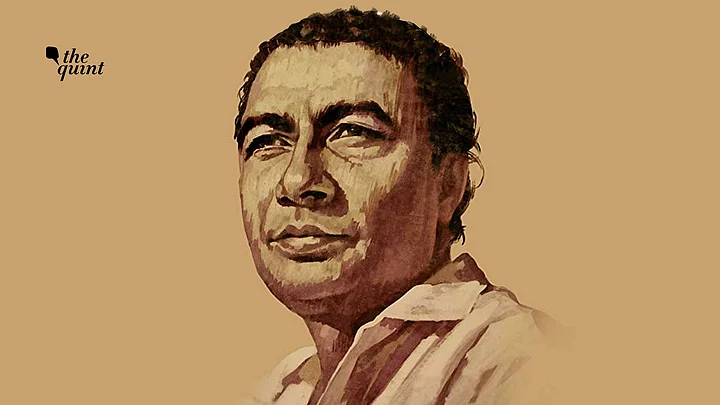

(This article was first published on 6 March 2021. It has been reposted from The Quint's archives to mark the birth anniversary of acclaimed poet and lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi.)

Film lyricists have generally been, and still are, second class citizens in the film music pecking order. Everyone knows the names of singers, most know the music directors, but most lyricists, save a few, remain in the shadows. The awe and respect are missing.

There have been a few though who have walked shoulder to shoulder with music directors like Shailendra. But there has only been one who was ranked above them all.

Shailendra wrote on truisms without recourse to sermonising. These were delivered gently with kid gloves.

The Unvarnished Truth

But only one person managed to take off these gloves and punch the listeners right in the face with unvarnished truth. He caught them by the scruff of their neck and held the mirror of society to them. He made them wince at the harsh truths, and forced them to reflect, to acknowledge, to act.

He lifted the carpet and threw the dust underneath at them. He was uncompromising and unafraid; he had integrity and he had talent — unimaginable amounts of it.

Sahir Ludhianvi was born Abdul Hayee to a decadent zamindar; his mother Sardar Begum being the eleventh wife out of twelve. His dissolute ways forced her to leave her husband with Abdul. But litigation and physical threats deprived Abdul of childhood. The father’s wanton ways, the ill-treatment of his mother, and the uncertainty of those years remained bitter memories.

“Duniya ne tajurbaat -o- havaadis ke shakl mein, Jo kuch mujhe diya hai, lauta raha hoon main”

Sardar Begum’s Influence on Sahir’s Poetry

Brave is the man who can bare his soul to the world and draw from his experiences to express himself. The memories of his childhood were funnelled to his writing. Poetry became a matter of cathartic release for him. He placed his mother on a high pedestal. If his poems and songs in later years eloquently expressed the plight of women, this was due to the challenges she faced.

In ‘Jinhe Naaz Hai Hind Par’ (Pyaasa, 1957) he wrote on the plight of women in the ‘badnaam bazaar’ in a hard-hitting way – “Yahaan peer bhi aa chukey hain, jawaan bhi/ Tan-o-mand bete bhi, abbaa miyan bhi/ Yeh biwi bhi hai aur behen bhi aur maa bhi / Jinhe naaz hai Hind par woh kahaan hain”. In Sadhana (1958) he wrote:

“Aurat ney janam diya mardon ko, mardon ne usey bazaar diya/ Jab jee chaahaa kuchlaa maslaa, jab jee chaahaa dutkaar diya”

In Trishul (1978), he did something totally unexpected. Opposing the traditional view that a mother’s duty is to offer shelter to her young son, he wrote:

“Main tujhe raham ke saaye mein na palne doongi/ Zindagaani ki kadi dhoop mein jalney doongi/ Taaki tap-tap ke tu faulad baney/ Maa ki aulad baney.”

Sahir would take a different angle, would think on a tangent, and make one introspect and marvel at his novel way of viewing things.

No Art for Art’s Sake

The other major influence on Sahir was that of the Progressive Writers Movement (PWM). He subscribed to PWM’s view that literature could not exist in isolation, as art for art’s sake. It was to be used to bring about a social change. As a result of his childhood experiences, which nurtured a distaste for zamindars and capitalism, his interest in communism, and involvement in student politics in college, he was naturally drawn to the PWM. Unlike traditional Urdu poetry, which was centered on husn, saaqi and ulfat, progressive writers wrote on the mazdoor, the muflis and the jamhoor.

Sahir’s initial forays, because of his college romances, were directed at love. Ultimately, he began to raise crucial questions about the world around him. Love for the beloved transformed into love for the entire world. In Didi (1959), he wrote:

“Zindagi sirf mohabbat nahin kuchh aur bhi hai/ Zulf-o-rukhsar ki jannat nahin kuchh aur bhi hai/ Bhookh aur pyaas ki maari hui is duniya mein/ Ishq hi ek haqeeqat nahin kuchh aur bhi hai/ Tum agar aankh churao to yeh haq hai tumko/Maine tumse hi nahin sabse mohabbat ki hai.”

A Hopeful Cynic

If his poems and lyrics had a bitter tenor to them, it was because he was overwhelmed by the circumstances around him. It was this rare sensitivity towards the plight of the exploited sections that formed the cornerstone of his poetry. In his much-acclaimed poem ‘Talkhiyan’, he powerfully spoke of the structures of exploitation and their agents like the capitalist, the usurer, the priest, and others.

While he critiqued the nation, and was cynical of politics, he never lost faith in the collective power of people. He urged the masses to bear the injustices a little longer while giving them hope of the arrival of a better tomorrow. In Phir Subah Hogi (1958) he wrote:

“In kaali sadiyon ke sar se, jab raat ka aanchal dhalkega/ Jab dukh ke baadal pighlenge, jab sukh ka sagar chhalkega/ Jab ambar jhoom ke nachega, jab dharati naghmein gayegi / Woh subah kabhi toh aayegi”.

Defying the Vanity of an Emperor

One other example of Sahir jettisoning the conventional approach was seen in his poem ‘Taj Mahal’. Instead of seeing the monument as an ode to love, Sahir decried the vanity of an emperor in using the wealth at his disposal to create a structure that would forever mock the love of ordinary people. A shorter version of this poem was used as a song in the film Ghazal (1964):

“Ik shahanshah ne daulat ka sahara lekar/ Hum gareebon ki mohabbat ka udaayaa hai mazaak / Mere mehboob kahin aur mila kar mujhse”.

When he joined the film industry, the producers were not willing to risk a poet doing a lyricist’s job; they were apprehensive about introducing a literary element in a medium that otherwise catered to the masses. They were mistaken and his songs became hugely popular. He proved that film songs and good poetry were not contradictory. He gave film songs an intellectual quotient. His verses never lacked in virtuosity or depth. They had unmatched poetic quality, aesthetic finesse, refined language, and beautiful imagery. His words went beyond film situations and became larger statements regarding life and humanity.

Consider these stanzas from the song ‘Main Zindagi Ka Saath’ from Hum Dono (1961) – “Barbadiyon ka sog manana fizool tha / Barbadiyon ka jhashan manata chala gaya “; “Jo mil gaya usi ko muqaddar samajh liya /Jo kho gaya main usko bhulata chala gaya”; “Gham aur Khushi mein fark na mehsoos no jahaan/ Main dil ko us muqaam pey lata chala gaya.” The song goes way beyond the context of the film and becomes a philosophy of life.

Sahir wrote on a variety of themes — romance, despair, cabaret, freewheeling ditties, agony, human relationships, philosophy, catharsis, existential questions. They had a strong visual aspect to them. He took recourse to nature’s beauty for romantic themes, synthesising nature with love and using nature’s breathtaking splendour to draw a parallel with the emotions one experiences in love.

In Humraaz (1967), he wrote: “Shabnam key moti, phoolon pey bikhrey / Dono ki aas faley / Neele gagan ke taley, dharti ka pyaar paley”. In Jaal (1952), in the song ‘Yeh Raat Yeh Chandni Phir Kahaan’ he wrote – “Pedon ki shakhon pey soyee soyee chandni/ Tere khayalon mein khoyee khoyee chandni/ Aur thodi der mein thak ke laut jayegi/ Raat yeh bahaar ki phir kabhi na aayegi/ Do ek pal aur hai yeh samaa/ Sun ja dil ki daastaan.”

Sahir’s Relationship With Love

One of the most intriguing aspects of Sahir’s life was his relationship with Amrita Pritam – already married. Their relationship was defined largely by silence. She was deeply in love with him. When Sahir’s alleged affair with singer Sudha Malhotra came to light, a distraught Amrita wrote some of the most despondent poetry during that period. She separated from her husband and lived the rest of her forty odd years with Imroz. Sudha got married and that was the end of her supposed liaison with Sahir. Sahir’s failure to convert his relationships was his unwillingness to share himself with anybody else except his mother.

However, these romantic relationships yielded classic songs such as “Jaane woh kaise log thay jinke, pyaar ko pyaar mila” (Pyaasa, 1957) and the ultimate break-up song from Gumraah (1963) – “Chalo ek baar phir se, ajnabi ban jaayen hum dono” (published as a poem ‘Khubsoorat Modh’ earlier in ‘Talkhiyan’). He articulated everlasting romance in “Jo waada kiya woh nibhana padega” (Taj Mahal, 1963) and took a gentle jibe at cold-hearted women with – “Jo inki nazar se khele/ Dukh paaye, mussibat jheley/ Phirtey hain yeh sab albele/ Dil lekey mukar jaane ko” (Munimji, 1955).

Sahir believed in the present, in the now – “Aage bhi jaaney na tu, peechhe bhi jaaney na tu / Jo bhi hai bas yahi ik pal hai” (Waqt, 1965); “Zindagi hasney gaane ke liye hain pal do pal/ Ise khona nahin, kho ke rona nahin” (Zameer, 1975).

Sahir had a multi-faceted view of India. On the one hand, he lamented the decadence –“Yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaaye to kya hai” (Pyaasa, 1957) and “Cheen-o-Arab Hamara/ Rehne ko ghar nahin hai / Hindustan hamara” – a satirical take on Iqbal’s poems (Phir Subah Hogi,1958). But he was also a patriot – “Yeh desh hai veer jawaano ka” (Naya Daur, 1957), and showed optimism about the future of the country in “Jaagega insaan zamana dekhega” (Aadmi aur Insaan, 1969).

Sahir was an atheist. Having seen the communal riots in 1947, he scorned the custodians of religion in “Tu Hindu banega na Mussalmaan banega/Insaan ki aulad hai insaan banega” (Dhool ka Phool,1959) and “Sansar se bhagey phirtey ho/ Bhagwan ko tum kya paogey” (Chitralekha, 1964). He even scoffed at the Creator – “Aasmaan pey hai Khuda, aur zameen pey hum/ Aaj kal woh is taraf dekhta hai kum” (Phir Subah Hogi,1958). Yet that did not impact his song writing skills when religious fervor was called for – “Allah tero naam, Ishwar tero naam” (Hum Dono, 1961); “Hey rom rom mein basney waaley Ram” (Neel Kamal, 1968).

There is timelessness in Sahir’s songs. His work and its relevance are eternal. His songs have no shelf-life. As we celebrate his birth centenary today, this song from Kabhi Kabhie (1976) beautifully captures the eternal poet:

“Main pal do pal ka shaayar hoon, har ek pal meri kahaani hai, Har ek pal meri hasti hai, har ek pal meri jawaani hai”.

(Ajay Mankotia is a former IRS Officer and presently runs a Tax and Legal Advisory. This is a personal blog and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)