“Khishat nahi aana, aani Bajirao mhana” (not a penny in your pocket, but think of yourself as the king) is a phrase widely used in Marathi political and social discourse.

In the run-up to the recently concluded municipal corporation elections, it was used by Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadnavis to target Maharashtra Deputy CM and Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) leader Ajit Pawar, after the latter released the party’s manifesto, outlining a slew of promises for the Pune and Pimpri-Chinchwad municipal corporations.

Standing beside him were senior leaders of Nationalist Congress Party–Sharadchandra Pawar (NCP-SP), Supriya Sule and Jayant Patil, as the two factions decided to join hands in an attempt to reclaim what were once their unquestioned bastions from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Both Pune and Pimpri-Chinchwad—long dominated by the rashtravaadis until 2017—had slipped out of NCP control when the BJP swept the civic bodies that year.

Politically, Pune and Pimpri-Chinchwad occupy for the Pawars the same symbolic space that Mumbai does for the Thackerays. These were once power centres that shaped the NCP’s organisational strength, leadership pipeline, and financial clout for decades.

Against that backdrop, the decision of the two NCP factions to reunite for the civic polls appeared logical, if not inevitable. Yet, the outcome of the municipal corporation results paint a grim picture for both.

Looking at Maharashtra’s last three electoral contests, a striking pattern emerges. Sharad Pawar’s faction outperformed rivals in the Lok Sabha elections, Ajit Pawar’s faction fared better in the Vidhan Sabha polls, but neither managed to assert dominance in the municipal corporation elections — arguably the arena where cadre strength and grassroots control matter most.

This raises a set of uncomfortable but unavoidable questions for the two parties:

Did the reunion actually help?

Are the Pawars electorally stronger together, or does the alliance dilute their individual strengths?

And crucially, where does Sharad Pawar’s NCP go from here in Maharashtra?

To answer these questions, it is first important to examine what unfolded on 17 January.

Overall Numbers Paint a Grim Picture For the Pawars

Out of the 2,800-plus seats across 29 municipal corporations in Maharashtra, Sharad Pawar’s faction of the NCP emerged as the worst performer, winning just 36 seats.

In the Pune Municipal Corporation elections, the BJP secured a clear majority, winning 119 of the 165 seats, a sharp rise from the 97 seats it had won in 2017. While Ajit Pawar’s NCP won 16 seats in Pune and 36 in Pimpri-Chinchwad, the Sharad Pawar-led NCP managed just three seats in Pune and failed to open its account in Pimpri-Chinchwad.

In Mumbai, the NCPSP won just one of the 10 seats it contested. Its limited successes elsewhere were confined to Kalyan-Dombivli (1 seat), Sangli-Miraj-Kupwad (3), Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar (1), and Akola (3).

The party’s best performances came in Thane and Bhiwandi-Nizampur, where it won 12 seats each. However, these results are largely being attributed to the individual clout of the candidates and the direct involvement of senior leaders such as Jayant Patil in Thane and Suresh Mhatre in Bhiwandi-Nizampur, rather than to the party’s organisational strength.

Ajit Pawar’s NCP has secured 167 of the 2,869 seats across the state.

What Exactly Went Down in Pune and Pimpri-Chinchwad

Despite Ajit Pawar’s NCP being part of the ruling Mahayuti alliance at the state level, local BJP units in Pune were keen on contesting the municipal elections independently. That decision, seen as a calculated risk, ultimately paid off.

The Pawars had come together primarily to prevent a split in the traditional NCP vote base in what were once their strongest urban bastions. Instead, the consolidation did not translate into electoral gains and, by most measures, resulted in a deeper setback.

Ajit Pawar ran an aggressive campaign with a clear and repetitive message: that funds allocated by the Centre and the state for local development were not reaching the ground or benefiting ordinary citizens. However, political analysts point to two overriding factors that shaped the outcome—the sustained popularity of Devendra Fadnavis and the BJP in the Pune region, and the party’s ability to showcase nearly a decade of visible development work.

The BJP’s organisational machinery in Pune also remains formidable, drawing strong support from sections of the upper castes, migrant communities, and long-settled urban voters, giving it an edge in ward-level mobilisation.

For the Pawars, candidate selection proved to be a double-edged sword, particularly in Pune. The decision to field Sonali and Laxmi Andekar, daughter-in-law and sister-in-law of gangster Bandu Andekar, drew criticism. Both won their seats even while lodged in jail. At the same time, other controversial candidates—Jayashree Marne, wife of gangster Gajanan Marne, and gangster Bapu Nayar—were defeated, suggesting mixed voter responses to such nominations.

That said, the Pawars managed to limit losses compared to their 2017 performance across both corporations. One factor that worked in their favour was the deliberate induction of new faces and first-time candidates, many of whom were instructed to focus intensely on hyper-local campaigning within their wards.

Throughout the campaign, Ajit Pawar consistently trained his fire on the BJP, levelling corruption allegations and questioning the party’s claims of development. He took on prominent BJP leaders tasked with working in Pune sucah as Muralidhar Mohor and Mahesh Landge. In the absence of a strong third alternative in in these regions, his sustained campaigning positioned him as the principal non-BJP option for voters, even if that did not ultimately translate into seats.

Ajit is Pushing Through, But What About Sharad Pawar?

Ajit Pawar currently holds an advantage in Maharashtra politics by being part of the ruling Mahayuti government and 35 MLAs in the state Assembly. Sharad Pawar’s strength, on the other hand, lies in Parliament: his faction has eight MPs in the Lok Sabha, compared to one from Ajit Pawar’s NCP.

Both factions, therefore, have different strengths. Leaders and workers across the two sides have often said that staying divided serves little purpose, given that neither faction is strong across all levels of elections.

The decision to come together for the Pune and Pimpri-Chinchwad municipal elections did not result in electoral victories, but it was not a complete failure either. The alliance appears to have helped consolidate the Pawars’ core voters in these regions and prevented a sharper decline in their seat share.

Individually, both factions have an average vote share of around 10%. But Ajit Pawar’s performance in the 2024 Assembly elections was also aided by support from NDA voters, a factor that continues to shape his position within the state.

The bigger challenge lies before Sharad Pawar’s NCP (SP). Even within the Maha Vikas Aghadi's (MVA) dwindling supporters, Uddhav Thackeray remains the most popular face. But recent municipal results suggest that the Shiv Sena (UBT)’s influence is largely limited to Mumbai.

Thackeray’s decision to not ally with the Congress and instead reunite with Raj Thackeray helped both Sena and Congress parties electorally, but it also showed that their core voter bases remain distinct.

The Congress, meanwhile, secured 324 seats across Maharashtra in the municipal elections and performed better than expected in Mumbai, winning 24 seats. While these numbers may not appear significant on their own, the party emerged as the single largest party in four municipal corporations and finished second in five others, indicating steady gains.

The municipal elections have clarified and reiterated a few hard facts:

Sharad Pawar’s NCP (SP) currently appears to be the weakest partner within the MVA.

The Congress is a more natural ally for the NCP (SP) than the Shiv Sena (UBT).

A Congress–Sena (UBT) alliance is not suatainable in the long run

A reunion of the two NCP factions may be necessary for organisational stability, though its long-term political impact remains uncertain.

For now, the two NCP factions are in talks about contesting the upcoming nagar panchayat and local body elections together. A joint meeting was held a day after the municipal results to assess the outcome. Ajit Pawar, however, said there were no talks about a merger.

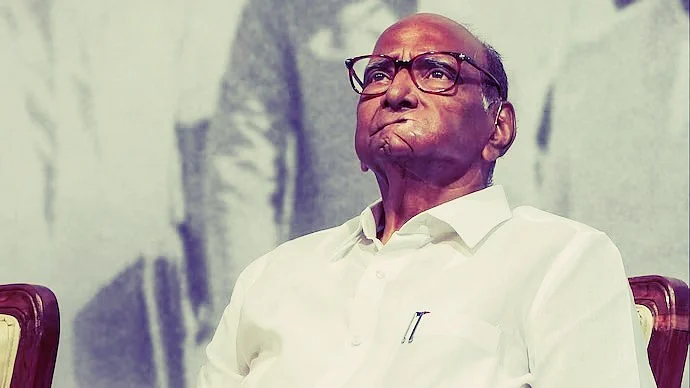

As far as Sharad Pawar is concerned - he was hailed as the youngest chief minister, a mass leader, a master strategist, and the kingmaker. But the outcome of the municipal corporatin results on 17 January indicate that the space available to his party in the state's political landscape has clearly narrowed.