The impeachment motion against Justice GR Swaminathan has opened a rare and combustible confrontation between India’s political class and its judiciary — one that tests the limits of constitutional morality, exposes deep ideological tensions in Tamil Nadu, and raises troubling questions about whether impeachment is being reimagined as a tool of political retaliation.

What should have remained a local, legal dispute over a small but symbolically charged ritual at the Thiruparankundram hill has now snowballed into a high-stakes national debate about judicial independence, political hypersensitivity, and the competing narratives around religious identity.

How a Local Ritual Became a National Political Flashpoint

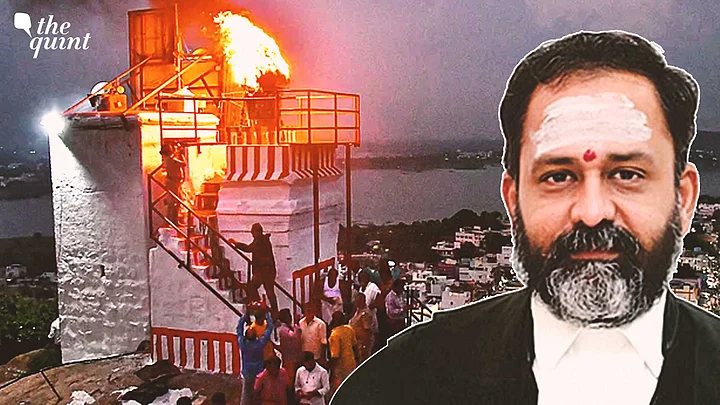

At the centre of the storm is Justice Swaminathan’s order from earlier this month, where he directed that a Hindu devotee be provided CISF protection to light a traditional lamp at the Deepathoon structure in Thiruparankundram, a hill revered both for the Subramaniya Swamy Temple and the Sikandar Badusha Dargah. For decades, the hill stood as a symbol of syncretic coexistence in Madurai’s cultural memory.

But recent years have turned it into a contested space, where competing religious claims, administrative ambiguities and political mobilisations have strained that delicate balance. Thus, when Justice Swaminathan ruled in favour of the petitioner, many in the DMK-led Tamil Nadu government saw it not as a straightforward legal question, but as an incendiary order that could inflame communal passions.

Following it, the government swiftly moved a division bench against it, only to face a sharp setback. The bench not only upheld the judge’s order but also criticised the state for filing the appeal merely to escape contempt proceedings.

Local Reality vs National Narrative

But in the foothills of Thiruparankundram, the narrative is far less dramatic than the one echoing in Delhi. Majority of the Temple priests across the State insist the ritual is routine, not inflammatory. N Mohammed Isbani, a resident of Madurai, who visits the Darga every year, argues that most of the local Muslims are not opposed to any lamp lighting. “What they oppose is the politicisation of the hill," he said.

According to Isbani, the residents of Tiruparankundram, beyond religious denominations, sees the annual Deepam lighting as a peaceful occassion, unless political leaders turn it into a flashpoint.

A retired police sub inspector, K Subramanian, who once handled the event, says the situation “needs sensitivity, not symbolism.”

“Thiruparankundram is not merely a location; it is a microcosm of Tamil Nadu’s complex religious landscape. The coexistence of the temple and the dargah atop the same hill has historically been held up as proof of the region’s syncretic ethos. But demographic changes, the increasing politicisation of religious spaces, and local administrative failures have turned the annual Deepam ritual into a tense affair.”K Subramanian

None of these voices saw impeachment coming. None imagined a local ritual dispute would travel from a hilltop in Madurai to the halls of Parliament. And none understand how this legal quarrel suddenly became a battleground for national political narratives.

Signatures That Lit the Fuse

On 9 December, the DMK and allied INDIA bloc MPs initiated an impeachment motion, accusing Justice Swaminathan of displaying ideological bias, undermining communal harmony, and violating the constitutional duty of neutrality.

At least 107 MPs, including all Lok Sabha members of DMK allies, General Secretary of AICC Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, National President of the Samajwadi Party Akhilesh Yadav, NCP-SP'S Supriya Sule, IUML's Asaduddin Owaisi, and others, have signed the petition to impeach the Madras High Court Judge.

Following this, constitutional experts, retired judges, and senior lawyers have since been warning that what is being projected as a defence of secularism may in fact be a dangerous assault on judicial independence, especially because the motion is built not on evidence of corruption or misconduct, the usual grounds for impeachment, but almost entirely on disagreement with the judge’s reasoning in specific cases.

Constitutional Roadblocks

To understand the gravity of what is unfolding, it is essential to revisit how impeachment functions within India’s constitutional architecture. Impeaching a High Court or Supreme Court judge is intentionally onerous: it requires signatures from 100 Lok Sabha MPs or 50 Rajya Sabha MPs, followed by an inquiry committee, followed by a two-thirds majority in both Houses for the removal to take effect. It has been invoked only a handful of times in the nation’s history. No High Court judge has ever been removed by this process.

The framers envisioned impeachment as a last resort for addressing corruption, ethical failure, grave misconduct, or actions that fundamentally violate the dignity of judicial office.

What impeachment was never meant for is punishing a judge for a judgment.

If impeachment becomes a response to a judgment, constitutional jurists warn, the judiciary will enter a danger zone from which return is nearly impossible.

Senior Jurist Warns of Deepening Crisis

Speaking about this, a former Supreme Court judge, who hails from Tamil Nadu, said on the condition of anonymity, “If this motion is admitted even symbolically, the message to judges is clear: don’t upset the government. That is the death of judicial independence.”

“Judges handling sensitive religious, caste, or minority-rights cases will have to calculate not just constitutional principles but political retaliation. The chilling effect may be subtle at first narrower interpretations, greater deference to the executive, more conservative rulings in religious disputes. But the long-term erosion will be profound.”Former Supreme Court judge

He further stated that if judicial reasoning becomes grounds for impeachment, the bench’s independence collapses. “The moment a judgment becomes impeachable, the Constitution stops protecting the judiciary. This is a cliff we should never approach,” he said.

DMK Frames It Differently

Arguing that DMK does not interfere in judicial freedom, the Deputy General Secretary of DMK and Rajaya Sabha MP Tiruchi N Siva, while speaking to The Quint, said that it is incorrect to claim that the INDIA bloc MPs initiated impeachment proceedings against Justice GR Swaminathan solely because of the Tirupparankundram case.

“In fact, the impeachment notice does not contain even a single reference to Tiruparankundram case. Back in August 2025, nearly 50 MPs from both Houses submitted around 13 detailed complaints to the President of India and the Chief Justice of India, alleging that Justice Swaminathan had failed to uphold his constitutional duties and had contributed to communal tensions through his actions and observations. While both constitutional authorities can receive such complaints, they cannot act on them. Only Parliament has the power to take action, which is why we have served the impeachment notice strictly on the basis of these 13 complaints, and not in any way connected to the Tirupparankundram matter."Tiruchi N Siva

The DMK’s concern is not merely legal; it is deeply political, rooted in its long-standing project of Dravidian secularism and its hyper-sensitivity to any gesture that could appear to validate the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP’s) Hindutva line.

Congress on the Backfoot

The Congress, which is part of the INDIA bloc, has tentatively backed the motion but finds itself in an uncomfortable ideological trap. Nationally, the BJP has already seized on the impeachment attempt to sharpen its narrative that the Congress alliance is “anti-Hindu,” accusing it of targeting a judge simply because he ruled favourably towards a Hindu devotee.

For a party already struggling with the perception of minority appeasement, the optics here are deeply unfavourable.

Indeed, the BJP appears to be the biggest political beneficiary of the crisis. In a state where the party is desperately trying to expand its ideological footprint, the impeachment motion offers it a potent narrative weapon. BJP leaders argue that the DMK is “intimidating the judiciary,” “punishing a judge for a religiously sensitive order,” and “playing with Hindu pride to strengthen its secular optics.”

Commenting on the issue, BJP Spokesperson Narayanan Tirupathy, told The Quint that the issue is being politicised by the DMK and its allies, and it appears to be driven by electoral calculations ahead of the Assembly elections.

“Their approach amounts to appeasement politics, aimed at securing minority vote banks by projecting the matter through a communal and emotional lens. The core issue, however, is the failure of the local administration and the police to comply with the High Court’s directions. This administrative lapse is the primary reason the situation escalated. It is the fundamental responsibility of the government and its officials to honour and implement the orders of the judiciary without any deviation.”Narayanan Tirupathy

A Narrative Battle with High Electoral Stakes

In Tamil Nadu, a state where the BJP has historically struggled to make inroads, a controversy of this kind offers a rare wedge issue. By positioning itself as the defender of devotees against an “anti-Hindu” political order, it hopes to push its narrative deeper into urban and semi-urban sections, especially among younger Hindu voters increasingly exposed to national Hindutva discourse.

For the DMK, therefore, the impeachment motion is politically high-risk. While it may consolidate minority support, it opens the door for the BJP and its allies to recast a local administrative dispute as a cultural war.

Whether or not the motion actually passes, and the arithmetic of Parliament makes that unlikely, the political messaging is clear, emotive, and easy to amplify. The BJP has found in this controversy an opportunity to revive its favourite allegation: that the INDIA bloc, and particularly the Congress and DMK, are hostile to Hindu concerns.

Substantiating it, whistleblower and journalist Savukku Shankar said that with Home Minister Amit Shah openly rejecting the impeachment move, the motion is almost certain to be buried by the Speaker, just like Deepak Misra episode

“Legally, it will amount to little. Politically, it may prove costlier than the DMK realises. The party has managed to antagonise large sections of the judiciary, inviting the risk of judicial setbacks on multiple fronts and in its zeal to signal that it will go to any extent to champion Muslim interests, the DMK and Congress has effectively written off the majority Hindu vote bank, walking straight into the BJP’s trap,” he said.

Is Judiciary Under Real Pressure?

But the political theatre around the impeachment motion obscures a more fundamental concern: what this moment means for India’s judicial future. If impeachment becomes a tool for punishing judicial reasoning, it threatens to chill judicial courage in sensitive areas.

Already, legal scholars point to an emerging pattern that the courts facing intense criticism or political backlash over decisions related to temples, festivals, caste-based reservations, and communal flare-ups. In such an environment, the fear of institutional retaliation through impeachment, transfer, or coordinated media campaigns can lead to a judiciary that is cautious, deferential and unwilling to confront the executive or assert minority rights.

When asked whether the BJP is dragging judiciary for its political benefits, Narayan Tirupathy denied it, saying “The matter is being unnecessarily politicised only by the DMK and its allies, creating divisions instead of ensuring lawful compliance. Any attempt to undermine a judge or the judiciary on grounds unrelated to judicial conduct threatens the principles of judicial independence. Such actions amount to an intrusion into judicial freedom and weaken the delicate balance between the branches of government.”

Countering it, DMK MP Tiruchi Siva said, “Our Constitution rests on three pillars: the Executive, the Legislature, and the Judiciary. When one of these pillars malfunctions, it becomes the responsibility of the others to intervene and correct the course.”

“The Judiciary has always been considered the last resort for ordinary citizens. A judge is expected to remain impartial and uphold the Constitution at all times. When a judge fails to perform his duties, or when his actions exceed acceptable limits, it becomes necessary for the Legislature to step in. It is only after witnessing a sustained pattern of conduct that we were compelled to initiate impeachment proceedings against him.”Tiruchi Siva

Legal Community Rallies Behind the Judge

Speaking on the legal perspective to The Quint, senior advocate Srinivasaragavan, who practices at the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court, said “Judicial independence is not a theoretical concept. It is a practical safeguard against the misuse of power. When a judge issues an order that displeases the government, the Constitution is meant to shield him or her from retaliation. But if that shield weakens even symbolically, the balance of power shifts decisively towards the political executive.”

“This is why the impeachment motion against Justice G.R. Swaminathan is not just a Tamil Nadu story. It is a national story with deep ramifications. It tests whether constitutional mechanisms will be used with restraint or repurposed for partisan battles. It tests whether judicial accountability will be conflated with ideological conformity. And it tests whether India’s democracy can still distinguish between disagreeing with a judgment and punishing a judge. It is doubtful whether the INDIA bloc MPs who signed the impeachment petition had read the said judgements of Justice Swaminathan pointed out in the notices.”Srinivasaragavan

Meanwhile, a section of senior advocates practising in the Madras High Court and its Bench at Madurai coming in rescue of Justice Swaminathan had submitted a memorandum to the Lok Sabha speaker Om Birla, on 12 December.

In the memorandum, pointing out the number of cases disposed of by Justice Swaminathan from taking oath as High Court judge, totalling 1,26,426 cases, including 73,505 main cases in eight years, they stated that the Motion of Impeachment as a direct attempt to destabilise the Judiciary in India through high-handed application of one of the most extraordinary provisions of the Constitution of India.

They sought to reject the Motion of Impeachment in limine by applying the principles of Articles 124(4) and 217 of the Constitution of India read with the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968.

In a recently released statement in solidarity with Justice Swaminathan, 56 signatories consisting of two former Supreme Court judges, five High Court Chief Justices and 49 High Court Judges have given a call to "Protect the Independece of the Judiciary."

The Precedent Will Remain

Even if the motion fails, as most legal experts expect it will, the damage may already be done. A precedent has been set: that impeachment can be invoked over a judicial order. That alone is enough to reshape how judges approach politically sensitive cases in the future. For India, a country grappling with deepening polarisation and increasingly frequent conflicts over religious identity, the consequences of suh a shift could be long-lasting.

In the days to come, as political parties sharpen their narratives and constitutional scholars debate the boundaries of “misbehaviour,” the real question is whether Parliament will treat impeachment as a solemn constitutional remedy or a political instrument. If it becomes the latter, the line between independent justice and political expectation may begin to blur and once blurred, it is exceedingly difficult to restore.

This impeachment motion may well fade away as a legislative footnote. But the warning it carries that judicial independence must be guarded from majoritarian and governmental pressure, will linger. At a time when India’s social fabric is already strained, the last thing the Constitution can afford is to let its judiciary become another battleground for political signalling.

(Vinodh Arulappan is an independent journalist with over 15 years of experience covering Tamil Nadu politics, socio-culture issues, courts, and crime in newspapers, television, and digital platforms.)