(The Quint has consistently given voice to those who have been wrongfully incarcerated. Help us do more such stories by supporting our special project.)

Trigger Warning: The interview includes references to torture.

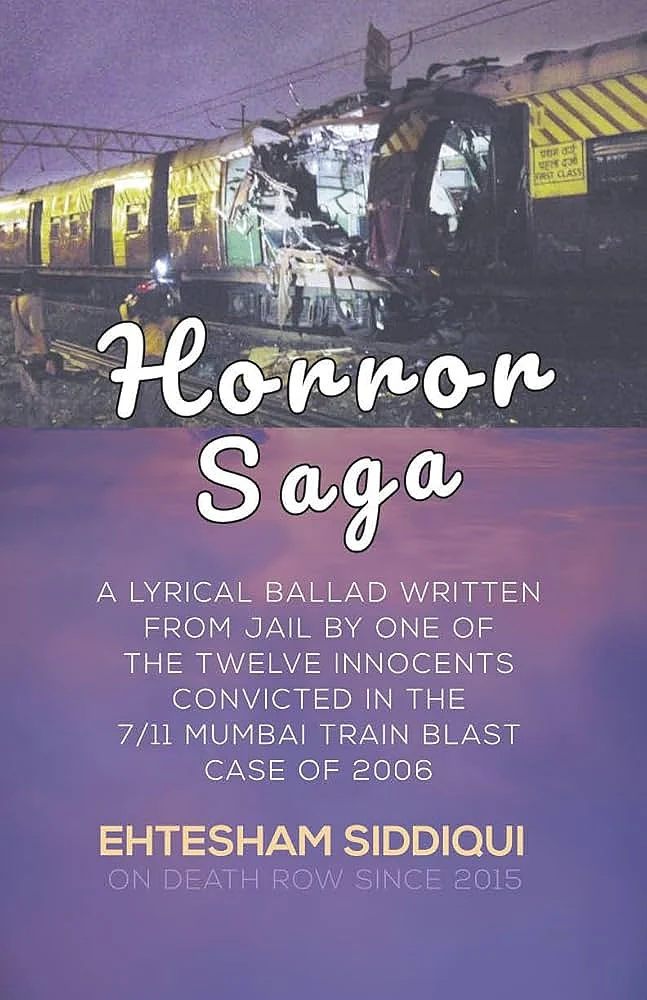

Ehtesham Siddique — one of the 12 men convicted in the 7/11 Mumbai train blasts and sentenced to death in 2015 by a special MCOCA court — has written Horror Saga, a book detailing how he was allegedly framed by the Maharashtra Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS), tortured in police custody, and witnessed corruption within the judiciary and prison system.

Though completed in 2018, the manuscript remained unpublished for six years due to bureaucratic delays but was finally published in 2024. After spending 19 years in prison, Siddique was acquitted by the Bombay High Court in July 2025.

In this interview, he talks about his life in custody through his book:

What prompted you to write a book documenting what you have alleged were fabrication of evidence, custodial torture, and systemic corruption in the judiciary and prison system during your case? After being sentenced to death in 2015, did you feel an added urgency to record your experiences and let the world know what you believe truly happened?

I genuinely believed the Sessions Court would acquit me but when I was convicted, a sense of fear set in. If the High Court upheld that verdict, the case could drag on for years— I wasn’t sure I would live long enough to see the truth come out and get my freedom. Everything I had gone through would remain buried, and no one would ever know my side of the story. That was one of the main reasons I felt compelled to write.

I initially wanted to narrate it in straightforward prose, but many others had already written similar accounts that way. I felt that presenting it in poetry would make the narrative more engaging and ensure people would actually read it.

Most people who go to jail describe their lives, everyday happiness and sadness. But in your book, there is almost no mention of your personal life or mundane things in jail itself. Instead, the book focuses entirely on the alleged fabrication of evidence, which you describe as "setting." Why so?

People often write about their day-to-day life in jail, and I have touched on those aspects too—but only in the context of exposing the corruption and the realities that exist inside. What I’ve tried to show is the gap between the state’s rhetoric and the reality on the ground. They claim one thing, but what actually happens is completely different.

Everything is interconnected—from the police to the jail system to the judiciary—and at the lower levels they operate in cahoots making it extremely difficult to get justice. In our case, it felt like everyone was determined to ensure we were all sentenced to death.The situation is different in the High Court and Supreme Court.

There is an officer who once served as Mumbai’s Police Commissioner. In press conferences, he spoke with complete confidence—projecting integrity, professionalism, and honesty. Whatever he said was accepted by the public as the truth. But the same man, when he met us privately during the period of custodial torture, was entirely different. What he said behind closed doors was the exact opposite of the image he presented in public.

This is the stark divide between rhetoric and reality. What is announced by the high command is one thing, but what actually happens on the ground depends on the officials implementing it. Only a handful truly follow the law with honesty, and even they are constrained by the system. Most simply follow the old, entrenched methods, especially during so-called “recoveries.” They don’t observe any legal procedure, yet on paper they claim to have followed everything by the book.

In India, if the police come to your house to conduct a search, who can really stop them? They will write within minutes that they visited, and the occupant “welcomed” them in. No one has the courage to refuse.

I once heard a story in jail: the police went to search an activist’s home. The activist asked for a written notice stating the reason for the search. The police responded, “Do you think this is a Bollywood movie?” That’s how due procedures are treated.

To what extent is it actually possible to implement the reforms, safeguards, and guidelines laid down by the Supreme Court, High Courts, and other higher authorities? Do you believe these directives ultimately make any real difference in the lives of ordinary people?

The Supreme Court, in the 2005 Prakash Singh vs. Union of India judgment, laid down a detailed roadmap for police reforms. Yet even after two decades, very little of it has been implemented. The reality is that those in power benefit from maintaining the existing structure. Allegations in cases like the Sachin Vaze episode—where investigations and media reports suggested he collected large sums of money from hotels at the behest of political leaders—illustrate the deep nexus between the police and the political class. They work in coordination, and in return, political leaders protect them.

Everyone in the system relies on the police, which is why reforms are resisted. You can see this clearly during elections: the Election Commission routinely transfers police officers so that this political–police nexus is disrupted and elections can be conducted fairly. That shows reforms are possible when there is genuine political will. If those in power truly want change, these guidelines can be implemented, and the police force can regain the trust of ordinary citizens.

Right now, the public perception of the police is largely negative—not because people inherently distrust law enforcement, but because the lived experience and the everyday conduct of the police has eroded confidence. If the reforms mandated by the higher courts were actually put into practice, the image of the police and the justice system could improve dramatically.

When it comes to the judiciary, people hesitate to speak openly because they fear contempt of court. Yet, despite everything, people still place their hope in the judicial system—because whenever the state overreaches, the judiciary is the institution you can ultimately turn to. In our case too, for every excess we faced, we had to keep going back to the courts.

The higher judiciary generally delivers justice, but what I have written about concerns the lower levels of the system, where most people’s cases actually remain stuck.

Once a matter reaches the High Court or Supreme Court, the quality of scrutiny improves—but getting there is the challenge. And in this long journey, the conduct of advocates and public prosecutors plays a huge role. You must have heard the phrase, “Adjournment is an argument.” It means that simply getting the next date becomes a tactic. A hearing scheduled after two months can be pushed again and again, dragging a case on for years.

Often, when you file a matter, your own advocate may advise you, “This judge won’t be favourable; let’s wait until he’s transferred.” How can an advocate say that? Similarly, public prosecutors may try to delay proceedings if the bench is perceived as less favourable to the state. But fairness demands that they argue the case regardless of who is on the bench. Judges too are expected to deliver justice without fear or bias—so why does the system operate on the assumption that one judge will do something and another will not?

This leads to what the Supreme Court itself has described as “bench hunting,” where different actors try to get their matters listed before judges who they believe will be favourable. The reality is that public prosecutors, police, judges, and judicial staff are all state officials, and the alignment of their interests can shape how benches are formed and how cases progress. Occasionally, a bench may rule against the government, but more often than not, the perception among litigants is that decisions tend to favour those in power.

Most people believe that if you’re a suspect, the police call you in, question you, and if they’re satisfied you’re innocent, they let you go. But in your book, you describe the opposite—you say you were called, questioned, and once they became convinced you were not involved, that’s when they arrested you. Do you think this was something unique to your case, or is this a more common attitude and practice within the police?

This is not something unique to my case. In my experience, what happened was based on certain beliefs the police had about us. They believed that because we were Muslims, and were critical of the existing system and sympathetic to an “Islamic system,” it was better to keep us behind bars.

Their bigger problem was that they had been unable to trace the real perpetrators. They tried repeatedly, but they couldn’t find them, and in the middle of all this, the Malegaon blast also took place. The pressure on them from the top increased. Under that pressure, they created a narrative around the people they had already picked up as suspects

Their thinking seemed to be: these individuals are in front of us, they can be easily framed , their views don’t align with the system, so arrest them, keep them inside, and close the case. This relieved their pressure and allowed them to claim the case was solved.

Do you think this treatment was specifically meted out to you owing to your religious beliefs?

Many new constables were deputed there. When they were on duty, they used to read the book by Savarkar, because of which their mind was filled with anti-Muslim thoughts. The officers who presided over them, although, didn’t have any religious feelings. They would abuse a Hindu using the names of his God, and Muslims using Allah’s name, so they didn’t have any religion.

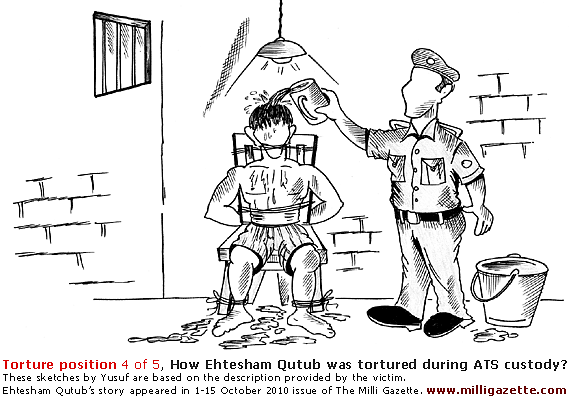

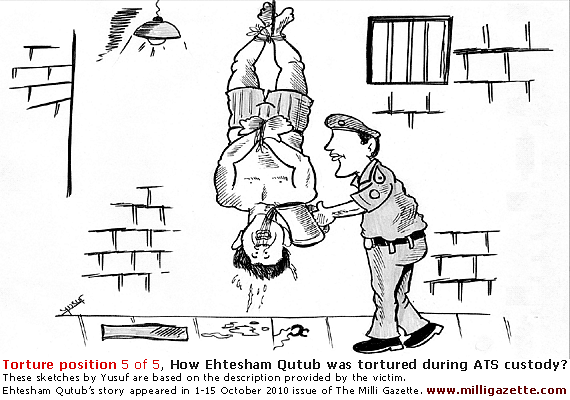

In your book, nearly 50 out of the 200 ballads are devoted to the torture you allegely faced in police custody. Could you describe the nature of that torture and what you had to endure during that period? Did this particular episode inspire the title of your book?

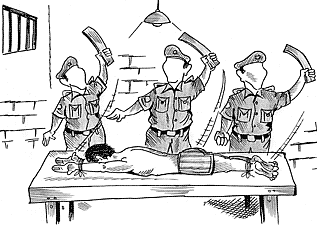

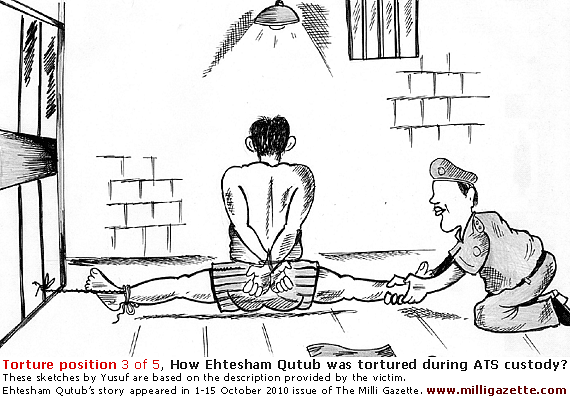

The torture began with the trampling of human dignity and the complete loss of control over oneself. It started with slaps and baton beatings, but soon escalated into far more brutal methods. A flour-mill belt was brought in, and one of the primary tortures was carried out using it. They would forcefully stretch our legs and make us lie down while one officer sat firmly on our shoulders, causing excruciating pain in the thighs and lower body. Then they would jump on our thighs, and when they suddenly released the pressure, the pain was so intense that veins would sometimes rupture.

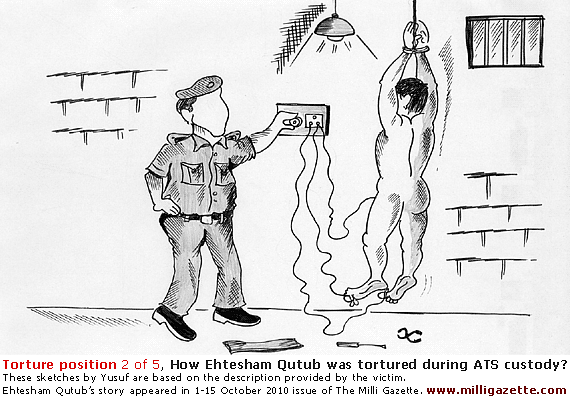

Stripping detainees naked was routine. If one tried to cover oneself out of instinctive shame, the officers thrashed his hands. They would even bring in family members while we were in that condition, humiliating us further and passing lewd remarks. Electric shocks were also administered as part of the torture.

They used Surya Prakash Oil, which caused severe burning sensations, and if we tried to wash them off with water, the pain only intensified. Waterboarding was another method: water was poured over our faces in a way that made it feel as if we were drowning.

They used to also burn our genitals and penis with lit cigarettes. They used to make us sit and bind us to the wall with our hands and feet firmly tied. The head is stuck to the wall with tapes so that you are unable to move your head at all. Then a bottle is tied over your head in a way that water drips on your head drop-by-drop for 8-10 hours. After sometime, you feel as if the water is drilling a hole in your head. It used to cause immense pain and psychological trauma.

Many other forms of torture were used—methods described not only in my book but also in another one, Innocent Prisoners, written by one of my co-accused. I witnessed the most horrifying experience of my life, and it was not a one-time incident. It seemed to us like a long night that would never end. It is after this reality that I have named the book Horror Saga.

Do you think that this book is a sign of a living conscience that you have written it?

Yes. When I was writing the book, I often asked myself whether this was an act of conscience. I knew that if the jail staff discovered what I was documenting, I could face pressure or harassment for exposing the realities inside the prison. I didn’t know for how many more years I would have to remain there, and that uncertainty created real fear.

But then I reminded myself that throughout my life—and even through this entire ordeal—I had not abandoned the path of truth. So I felt I should not stop now. I decided to take a principled stand and write exactly what I had experienced, without hiding anything.

That’s why, in the final paragraph, I say that this is the truth, and instead of taking offence, the system should focus on correcting what is wrong. In that sense, yes—the book is an expression of a living conscience.

In the opening paragraph of your book, you write that once the first arrest is made, the entire system gets involved in fabricating evidence—and that your own case rests completely on such fabrication. According to you, when did this fabrication begin, and what triggered it?

The first ballad refers to the 2001 Kurla case, which is where, in my view, the fabrication began. I was in the library at the time, along with several others. The SIMI office was located behind it. When the police arrived, they were supposed to come with 2-5 witnesses for a lawful search. Instead, a large force turned up, ordered all of us into their vehicle, and took us to the police station.

After that, they searched every corner of the library and the office, collected whatever they could, and brought everything back to the police station. It was there, seated inside, that they decided what would be turned into “evidence.” They began questioning each of us one by one: Which class do you study in? How old are you? If someone was very young, they let him go. Out of everyone present, they selected eight people they wanted to arrest.

To justify these arrests to the court, they needed to show that incriminating material had been “recovered.” At that time, an Urdu magazine called Nayi Duniya had a full-page photograph of Osama bin Laden on its last page because the issue had been published around the time of 9/11. The police brought that magazine in and wrote in the panchnama that this photograph had been found on us and that we were spreading his ideology.

Once they had written out the seizure memo, they called the witnesses and took their signatures. This document was then presented in court to create the impression that serious material had been recovered from us—so serious that we were real threats to the nation.

This, in my view, is how the fabrication started: evidence was created to convince the court, and the court trusted what the police had written.

In the final three lines of the ballad, you write that "because this was a setting, hence forget about telling anybody what had happened in custody." You and your co-accuseds have been maintaining since 2006 that all of you are innocent. In that context, what exactly do those lines mean?

In common language, “setting” means getting work done through corrupt or undue influence. If someone has a “setting” with the police, the police helps them; if they have a “setting” with a judge, the judge favours them. In my case, the situation was such that the police, judiciary, and prison system seemed to function as one. In theory, there is a division of power between executive, legislature and the judiciary. But it only exists in theory.

What I witnessed in police custody and in prison was deeply disturbing. There should be absolutely no police interference inside a jail, yet senior officers repeatedly visited the prison, pressurising us, trying to turn us into approvers, and attempting to lure us into agreements.

Even in court, conversations about our case happened behind closed doors. Judges spoke privately with police officers in chambers. Any discussion affecting an accused person should take place openly in court, yet the process was anything but transparent. A police officer who had been stationed in court for years was praised in our judgment for “assisting” the court. But in reality, his assistance consisted of influencing the judge to convict us despite the absence of evidence. This is what I refer to as “setting.”

Another pattern I saw was the exchange of favours. Judges transferred from other cities sometimes needed logistical help, such as retrieving their belongings or arranging their children’s school admissions. When police officers facilitate these personal matters, it creates an informal network of obligation. There may be no direct exchange of money, but such favors constitute a subtler form of corruption that compromises judicial independence.

The third layer is actual monetary corruption. Everyone knows corruption exists in the jail system, but very few understand how it functions in the judiciary. For example, something as simple as obtaining a certified copy in a Sessions Court becomes a chain of informal payments. If you file the application yourself, it may not be accepted. You are told to go through an advocate, and then you are told there are “expenses” at every level—from the peon who searches for your file, to the clerk who photocopies it, to the staff who verify it, and finally the registrar who signs it. Without these payments, your copy may be delayed for months.

Most judges do not take money directly, but the ecosystem around them—staff, clerks, intermediaries—is deeply compromised. Judges, too, often operate through favours rather than cash. At the higher levels, especially in constitutional courts, we are told that neither money nor strong legal arguments matter as much as personal familiarity with the judge. This, too, is a form of corruption.

As for my purpose in repeating those lines again and again was simple: I wanted to shout from the rooftops that this happened to me. But no matter how loudly I shouted, or how much noise I made, nothing changed. People find it impossible to believe that such things can happen, and that disbelief itself becomes a barrier. That is why I kept repeating it — to force people to confront the reality that they refuse to see.

I wanted to highlight the nexus — the system of influence and favours — even more than I wanted to proclaim my innocence. Because unless people understand how the nexus works, they will never understand how easily a person can be trapped. The repetition reflects the helplessness of an individual who realises that the only way to make sense of his suffering is to recognise this system, this machinery, that operates beyond his control.

A normal person in India knows that you need "setting" especially if the police are involved, even if the work is trivial. If you want to get a passport made and need police verification — it is the job of the police, they need to verify it, it is the law — but what do they do? Everyone knows. If you want to get a document made, you need to get the "setting" done else you won’t be able to get it made. The public knows that everywhere you need some "setting", and the judiciary is not separate from that.

In the last ballad I wrote, I finally said what I had carried within me for years. I have stated it openly: this is what happened to us. I am informing everyone, not because I expect relief or benefit, but because the truth deserves to be heard.

In your book, when you describe how the police built a case against you, you use words like “cooking” or “fabricating.” These are strong allegations against the police. When you look back at it today, has your perspective changed?

There is no change. Even today, the situation remains the same. Even when the police are able to solve a case and identify the real perpetrators, they still fabricate. Why? Because they themselves don’t trust that the case will hold up in court on the strength of the evidence they actually have. So instead of presenting what is genuine, they add layers of fabrication to make the case appear stronger.

In their view, the case has to “stand,” and to ensure that, they construct or exaggerate parts of the narrative. This attitude has not changed at all.

Whatever you have written, an ordinary reader will struggle to believe it. People know, in a general sense, that corruption exists in the police. But they don’t imagine it operating at this scale. It is not part of the common perception that the police would go as far as falsely accusing someone in a case where so many lives were lost. Do you feel that the government can go to any extent to protect its own legitimacy — even if it means sacrificing the life of its own innocent citizens?

In my view, this is true. People who rise to certain positions in the state machinery — not just elected officials, but senior officers and institutions — develop a strong instinct for self-protection. Once someone reaches that level, their priority becomes safeguarding themselves, their reputation, and their department. And when that instinct kicks in, they are capable of going to any extent.

After the blasts, the entire population was in shock and anger. Protests were happening everywhere, and the public was demanding immediate arrests. Under that pressure, the government pushed the police for quick results. Officers were told that if they failed to find the culprits quickly, they could lose their postings or face transfers from their prestigious postings in Mumbai.

So while the police may initially try to trace the real culprits, when they fail, the pressure leads to shortcuts. That is when innocent people get rounded up. This is especially common in blast cases. These are extremely serious offences, but in many such cases across the country, courts have later ruled that people initially arrested were not the actual perpetrators.

Examples often cited include the Mulund and Ghatkopar blast cases in Mumbai, the Malegaon 2006 case, and the Mecca Masjid blast case in Hyderabad — where those arrested were later found not to be involved.

Based on everything I have seen and experienced, my belief is that in a significant number of such cases — perhaps 70 to 75 percent — the real perpetrators escape, while others get arrested under pressure, panic, or the desire to quickly close the case.

We see stock witnesses like Vishal Parmar coming up repeatedly. Some people say that just as the police have stock witnesses, they also have stock suspects. What is your view on this? Do the police maintain a list of recurring suspects for different kinds of cases, such as murder or dacoity, so that if they can’t find the real culprits, they can arrest these individuals?

Yes, I have noticed this pattern in many cases. For example, consider a minor case like mobile phone theft. You go to the police station, register a complaint, and they write an NC. The case is officially registered, but if the accused cannot be found, the case remains pending.

Now, suppose 50 other people register similar complaints about theft. All those cases stay pending as well. If the 51st complainant comes in and the police manage to find someone they can blame, they often charge him with all the previous cases. Once someone enters the police records in this way, they become a “stock suspect.”

From that point, the police call him frequently, interrogate him, and check whether he can be implicated in new cases. If they conclude that arresting him will not create major problems or that he won’t give evidence that could harm their service record, they proceed to arrest him. Over time, this creates a pool of individuals who can be repeatedly used as convenient suspects whenever the police need a quick solution.

You write that "human rights is a bluff.” We have the ICCPR, we have fundamental rights, and we have an entire constitutional framework that promises dignity and protection to an arrested person. Yet the police often act with complete impunity.

Given this contradiction, how do you understand the gap between the human rights discourse and the reality on the ground?

Whether it is police custody or jail, there are clear rules about how a detainee should be kept and how their rights must be protected. These laws exist in the Police Manual, the Prison Manual, and in every human rights guideline. On paper, everything looks perfect.

But the moment a person actually enters police custody or jail, they realise that none of these rules matter. Nothing is followed. Everything depends on the whims and wishes of the officers in charge. The law is written in books, but reality is governed by those who hold power inside the lockup.

When we were taken in, the way we were treated had no connection with the rules. We were denied proper clothing, kept only in underwear at times, and often kept awake continuously — not just for hours, but for more than three days at a stretch. Sleep deprivation, humiliation, and torture were routine. The lockup conditions were inhumane.

So then the question is: Where are the human rights people? Where are the laws? Where are the protections we keep hearing about?

In Ballad No. 9 you write about “torture chambers.” Most people think police torture simply means being beaten, but what you describe goes far beyond that. It shows how torture has been systematised and almost legitimized through dedicated spaces and established methods.

Besides, everyone knows that custodial torture happens — from ordinary citizens to the judiciary. It is almost an open secret. So, in that context, how do you understand the idea of “setting”?

In my experience, when the police torture someone, there is a very clear pattern. In Mumbai — because it is a big city, and the media is alert — the police usually avoid leaving visible marks. But in the districts, they beat people brutally, without restraint. Even if someone is dragged into court limping or injured, and even if they openly tell the judge they were tortured, nothing happens. The judge doesn’t even look up.

In Mumbai, at least the Sessions Court judges record some complaints. Not everything we said was recorded, but a few things were. But in the lower court — in Mazgaon — they didn’t even acknowledge us. It was as if we were speaking to the walls.

Legally, every detainee must be examined by a doctor every 48 hours to check for injuries. The doctor is supposed to conduct a thorough medical check-up. But in our case, it was just a formality. We repeatedly told the doctor that we were in pain. Sometimes he would send us for an X-ray, but after receiving the report, the police would whisper into the doctor’s ear: “These are blast accused.” Immediately the doctor’s attitude changed: “Why have you brought such hardened criminals to me? What am I supposed to do?” Then he would simply sign the register without examining us.

This is where the “setting” becomes visible in the realm of nexus of medical professionals with police. And later, when these doctors come to testify in court, they say exactly what the police instruct them to say.

In our case, something unusual happened. The regular doctor — who usually cooperated with the police — was on leave. The substitute doctor honestly wrote down our injuries. Later, when we asked for the medical register in court, the police did not produce the reports which had documented our injuries; they selectively hid the entries.

We insisted. When we examined it, we found the injury entries right there. This should have shocked the judiciary. The moment such concealment comes to light, the court should take immediate cognisance and question the officers: “Why were these medical records hidden?”

But the court did nothing. Even recording such things was treated hesitantly.

In your view, why does the judiciary not act against the police in such cases? We understand there is a “setting,” but beyond that, what explains this silence? In many situations, the role of the police is evident — the patterns of torture are well documented, the violations are visible and proven through medical records, eyewitness accounts, and procedural lapses.

Yet, the judiciary still does not intervene or hold the police accountable. Why do you think this happens?

The question of “why the judiciary doesn’t act” has a very simple answer: who will act against oneself? The institutions are interconnected. There is a chain of relationships and dependencies between the police, the prosecution, and different levels of the judiciary. When one part of the system fails, the others rarely step in to correct it.

Take the Malegaon case as an example. The NIA’s investigation concluded that the earlier accused had been falsely implicated — that their confessions were coerced and that the evidence against them could not be relied upon. The Sessions Court discharged them.

But even then, the Sessions Court added that their discharge does not automatically mean the police will be prosecuted. That raises a very basic question: why should the role of the police not be examined? Lives were destroyed, families suffered, careers ended. If people were wrongly accused, the process that led to that should be scrutinised. Otherwise, how will trust in justice survive?

In my view, the state should have ordered an inquiry into the false implication of innocent people. Instead, what happened? As soon as the discharge order came, the state immediately filed an appeal in the High Court. That appeal has now been pending for twelve years. Why is it not being heard? Why is there no urgency?

One more problem is that unless someone personally goes to court and pushes the case, it simply doesn’t move. This happened in our matter as well. My advocate had to file a petition in July 2024, saying that the case had been pending for ten years and that a bench needed to be constituted. Only after that the court formed a special bench and began hearing the matter.

You have written the book in the format of a ballad. Each ballad has 14 lines, and the last three lines are repeated across all the ballads. The 12th line—“because this was a setting”—is sharp and direct. How did you arrive at this particular format? Why 14 lines, and why this structure?

The 14-line structure actually comes from the sonnet form. When I read about sonnets, I noticed that most of them use 14 lines, and that gave me a framework. Initially I tried writing the ballads in 8 or 10 lines, but I realised I couldn’t fit an entire incident into such a small space—especially because the last three lines were essential and had to repeat across all the ballads. Without those three, I was left with only 6 or 7 lines, which wasn’t enough to convey the full context or gravity of an event.

So I chose 14 lines. The first ten let me describe the incident fully. The 11th line acts like a pivot—it summarises the contradiction between what the state says and what it actually does and tries to give a sharp comment on the incident mentioned above. And the last three lines repeat in every ballad to hammer the central question and the central problem. That repetition is deliberate: it forces attention and asks the state to take cognizance. The 12th line—“because it was a setting”—carries that stark reality, that we were not thrown into jail for any of our deeds but because of a "setting" and anyone can fall victim to that "setting."

And is there a specific reason that you wrote 200 ballads?

When I first began writing, I completed around 70–80 ballads and set myself a target of 100. But then I realised that if I stopped at 100, the book would be too thin and I wouldn’t be able to cover the full story. Entire aspects—especially the part about the court—would have to be left out. Once I began writing about the court, the material kept expanding, and I understood that 100 ballads wouldn’t do justice to the scope of the case.

That’s when I decided on 200. This case has 200 victims: 187 who died and 13 who were arrested and had their lives destroyed. The number itself carries meaning. Writing 200 ballads allowed me to cover everything—from the beginning to the end—and to ensure that each victim’s place in the narrative was acknowledged.

Where will this impunity take the discourse on ‘justice’?

It will ultimately lead to disastrous consequences. What these policemen are doing may benefit them temporarily, but it harms the entire country in the long run. When such abuse happens to only a few people, the rest of society may believe they are safe. But when it begins to happen to anyone and everyone—when every family suddenly finds itself targeted—it shakes the entire foundation of the system.

A state cannot survive if its people lose all trust in its institutions. If this pattern continues, it risks pushing the public towards anger, instability, and a complete breakdown of confidence in the established order.

What in your view could ensure that nobody undergoes what you had to go through? How can it be better?

The political leaders hold the reins of the country; they represent the nation. They first need to set themselves right. Yet, why is it that when a political party loses power, cases are often registered against the losing party? And these cases frequently involve crores of rupees, not just lakhs. Doesn’t this suggest that unless honest people reach the top levels, the system below can never be repaired? After all, if the foundation is shaky, the building cannot stand strong.

But don't you think that anyone who aspires to be part of the state is primarily motivated by money? If so, how can reform come from such individuals, or is there a fundamental mismatch?

That is exactly what needs to be corrected. People who genuinely want to serve the public should come forward and work honestly. India has had examples of such individuals. Lal Bahadur Shastri never spent on himself and was not involved in corruption. Maulana Hasrat Mohani, who was a minister, also never accepted money; he even turned down an MP’s salary. These examples show that honest, selfless public servants do exist, and they are precisely the kind of people needed at the top to reform the system.

(Osama Rawal is a student of law, translator, and journalist reporting on labour rights, human rights violations, civic issues, environment, and communalism. Nishtha Sood holds a degree in Politics and International Relations from SOAS, London, and writes on terrorism laws in India, linguistic movements, and issues of identity.)