At least one in four teaching posts are laying vacant across central universities in India.

Even as institutes rely more on contractual hiring to fill teacher vacancies, not more than ten percent of contractual teachers are re-employed.

Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) are brazenly defying reservation norms in hiring teachers belonging to marginalised communities.

These findings of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education, Women, Children, Youth and Sports were tabled in Parliament on 26 March. The report sheds light on the condition of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) as well as the status of central sector schemes in fulfilling their respective agenda.

In this story for The Quint’s State of Education series, we look at how HEIs across India are functioning without adequate teachers and how that affects the quality of education being imparted to students, and in turn, their employability.

After all, two in every three unemployed youth in India have completed secondary or higher education, as per a 2024 report released by the International Labour Organisation (ILO). It also points out that the unemployment rate among graduates stood at 29.1 percent— nearly nine times higher than the 3.4 percent for those who can’t read or write.

While this paradox is often attributed to a gap in technical, digital and soft skills, the bigger question is why can’t higher education institutes guarantee workplace readiness?

Thousands of Posts Vacant; 10 Universities Without a Regular VC

As of 31 December 2024, more than 5,400 teachers’ posts are lying vacant in the 57 central universities (CUs) across India. In addition, over 17,200 posts—nearly half the sanctioned strength—of non-teaching staff are vacant.

The Board of Apprenticeship Training (BOAT), which provides industry-training to graduates to ensure their employability, has nearly 16 percent unfilled teaching positions.

Moreover, the following Centrally Funded Technical Institutes (CFTIs) have at least one vacant teacher's post in every four:

National Institute of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, Ranchi (Jharkhand)

North Eastern Regional Institute of Science and Technology, Itanagar (Arunachal Pradesh)

Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal (Punjab)

Central Institute of Technology, Kokrajhar (Assam)

Ghani Khan Choudhury Institute of Engineering and Technology, Malda (West Bengal)

Among central universities, the vacancies for posts of Professors are the highest—more than half the posts for professors are vacant. While Professors have a PhD and 10-plus years of experience, assistant professors are entry-level teachers without the mandate of having a doctorate.

The Committee took note of the “very high number of vacancies” for faculty and administrative staff in central universities and stated that it impacts the faculty-student ratio and dilutes the quality of teaching in such institutions.

It was “deeply anguished” to note that up to ten central universities are running without a regular Vice Chancellor, adversely affecting the critical role in appointing faculty and non-faculty members and overseeing the implementation of development plans.

The Director’s position at the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies (IIAS), Shimla has been vacant since August 2021. Similarly, Banaras Hindu University’s Executive Council has been defunct since June 2021.

Yet Only a Small Percentage Were Filled

Despite there being over 5,400 vacancies for teachers in central universities in 2024, only 721—or less than 15 percent—have been filled as of 31 January 2025.

Meanwhile, among non-teaching staff, over 16,600 posts were vacant as of 31 January 2025. Of these, 4,120 posts were advertised, and 3,700 posts were filled—clearly indicating that there is enough supply of staff to fill up the vacancies.

The question then is why weren’t the remaining 75 percent of the posts advertised?

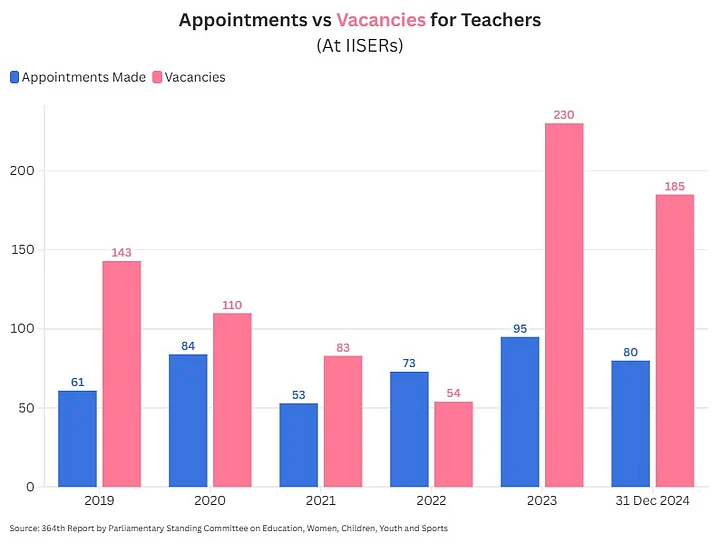

In the seven Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISERs) located across India, there were 185 vacancies for different faculty positions in 2024. Yet only 80 or 43 percent of the total vacant posts were filled.

Similarly, in 2023, 41 percent of the total vacancies were filled. This is when the sanctioned strength for faculty was increased by 225 posts.

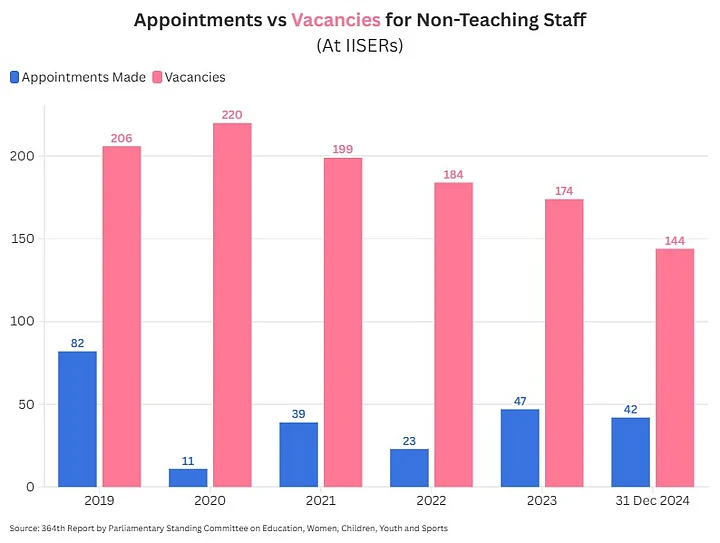

The condition is even worse for non-teaching staff, with only 29 percent of the vacancies being filled in 2024.

The Committee recommended that a regular analysis of the workforce be conducted, which identifies current and future staffing requirements based on the number of students enrolled, faculty retirements, while keeping in mind evolving academic programmes and administrative requirements. It asserted that the the recruitment process should be transparent and non-discriminatory.

More Contractual Hiring But Few Re-employed

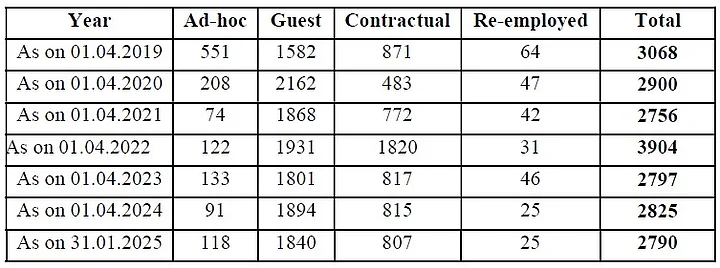

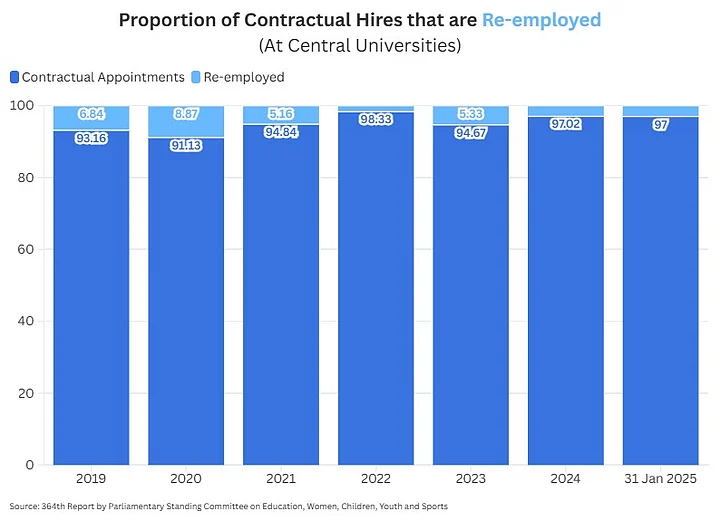

Another interesting data point emerged when we looked at the breakup of non-permanent teachers in central universities. A miniscule percentage— under 10 percent—of those hired contractually are actually re-employed.

The Committee noted that while industry experts can add value as guest lecturers, regular teaching positions should be filled by qualified academic professionals with proper training in pedagogy.

In the five CFTIs, almost as many teachers were hired on a contractual basis as there were regular appointments—which is a worrying trend both in terms of the job stability of the teachers as well as the quality of education delivered to students.

Data from the report shows that both regular and contractual appointments formed only a miniscule proportion of the total 1,388 sanctioned posts. For instance, as of 31 December 2024, 374 posts are vacant, and yet only 33 teachers were hired—which is less than 10 percent of the total vacancies and merely 2.38 percent of the total sanctioned strength.

The Committee recommended that a structured plan be created to phase out excessive contractual employment and recruit qualified faculty into permanent positions with job security and fair wages.

While noting the reliance of HEIs to fill vacant seats on contractual/short-term, the Committee said that it should not undermine reservations for marginalised communities as it weakens academic freedom.

Faculty Strength at IITs, IIMs Defy Reservation Norms

If we look at the IITs, of the total 7,370 teachers in position, only 4.85 percent belong to Scheduled Castes (SC), 1.1 percent belong to Scheduled Tribes (ST) and 10 percent belong to Other Backward Classes (OBC).

This is in clear contravention with the reservations set by the government and Supreme Court orders as under:

SC—15 percent,

ST—7.7 percent,

OBC—27 percent.

In addition, 10 percent of seats are reserved for those belonging to Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) and 5 percent for Persons with Disabilities (PwD).

The situation is even worse in Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), where at least half of the 21 elite institutes don’t have a single teacher belonging to the Scheduled Tribe community. Again, the SC and OBC communities remain deeply under-represented across IIMs.

The Quint had earlier reported that IITs and IIMs were blatantly defying reservation norms relying on information received using the Right to Information (RTI) Act.

While shedding light on a plausible reason on the extreme under-representation of faculty from the ST community, the Committee illustrated:

Students from the Adivasi community seldom finish primary school and pursue higher studies up until a PhD. Which explains the difficulty in finding professors from the Adivasi community. The solution to this starts at the very grassroots, where Adivasi children are provided with a conducive environment to learn and they are encouraged to pursue higher studies.

The committee recommended the Department of School Education and Literacy to start programmes to this effect.

Data shows that the number of complaints of caste-based discrimination in higher educational institutions has also consistently risen over time.

The Committee reiterated the Supreme Court’s directive to HEIs to release data on the functioning of Equal Opportunity Cells, which deal with grievances of marginalised students.

Status of Mission Mode Recruitment for SC/ST/OBC Faculty

It was in August 2021 that Higher Education Secretary Amit Khare had directed all central universities, IITs, NITs, and IIMs to fill backlog teachers’ vacancies, especially for marginalised communities, on mission mode by September 2022. That year, 1,439 vacant posts were identified, of which, 449 were filled by reserved categories, according to a report by The Hindu.

Data from the Standing Committee report stated as of December 2024, over 26,750 vacancies have been filled. Of these, more than 15,600 were faculty positions and over 5,900 were filled by faculty belonging to marginalised communities (1,949 SC, 771 ST and 3,261 OBC).

In order to achieve the target of 50 percent Gross Enrolment Ratio in Higher Education by 2035, the committee recommended the following steps:

leverage technology to provide flexible learning options;

reaching students who cannot attend traditional institutions;

provide scholarships, grants, and affordable student loans to make higher education more accessible to economically disadvantaged students;

actively engage with communities to raise awareness about the benefits of higher education;

and increase government spending on higher education.

For FU 2025-26, the Department of Higher Education has been allocated over Rs 50,000 crore—which forms 38.93 percent of the total Budget allocation of Education Ministry. The remaining goes to the Department of School Education and Literacy (DSEL), covered in other stories in the State of Education series.

Besides, IITs have utilised 77.05 percent of the Budget allocated to it for FY 24-25 and have over Rs 2,400 crore unspent as on 31 December 2024. Similarly, NITs have utilised 72.5 percent of their FY 25 Budget and have over Rs 1,470 crore unspent. Both institutes have reported a drop in placements.