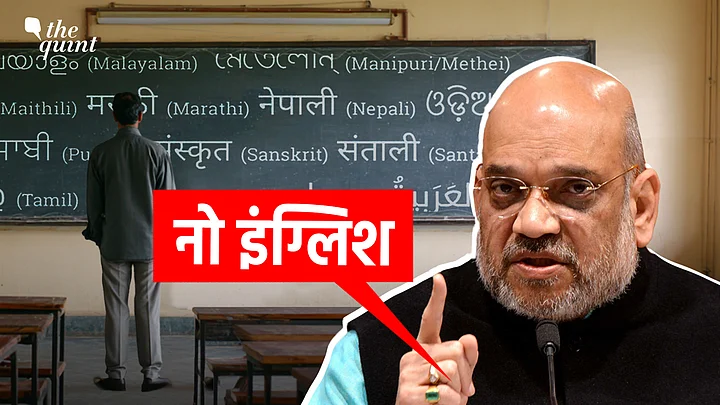

"Hum sab ke jeevan mein, iss desh mein, angrezi bolne waalon ko sharm aayegi, aise samaj ka nirmaan ab door nahi (those who speak English in India would soon feel ashamed; the creation of such a society is not far)."

Union Home Minister Amit Shah reportedly made this statement at a book launch in June. He also said India will soon be run using "our languages" and that "we will think, research, find solutions" in native languages.

In the current political landscape, language is more than just a medium of communication. Regional languages are increasingly being positioned as vital to cultural identity and national pride.

From BJP MP Nishikant Dubey refusing to speak in English as "it's a foreign language" in the ongoing Parliament session, to the Siddaramaiah-government equating learning Kannada to a civic duty, the assertion of linguistic roots is cutting across party lines and states. Meanwhile, Maharashtra witnessed a more extreme form of linguistic push(back) — a proposed Hindi mandate in schools sparked violent incidents, public protests, and fiery remarks from Opposition leaders.

But neither is this linguistic assertion new, nor is it restricted to political discourse.

It was in October 2022, that Shah launched the country’s first medical course in Hindi medium in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. He also highlighted PM Modi's vision to promote medical and engineering education in regional languages such as Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Gujarati, and Bengali.

The same year, the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) announced a ground-breaking decision to allow B.Tech programmes in 11 Indian languages.

Fourteen engineering colleges across eight states were allowed to offer regional-language instruction in selected branches starting from the next academic session.

However, four years later, the implementation of these goals tells a different story. A Right to Information (RTI) application filed by this reporter reveals that B.Tech programmes in several regional languages—including Bengali, Assamese, Punjabi, and Odia—have not been launched at all.

Meanwhile, B.Tech courses were introduced in Gujarati, Malayalam and Kannada but they failed to attract sufficient students, with admissions remaining negligible.

The exceptions here are Tamil and Telugu, and to some extent, Marathi. Engineering courses in these languages have seen steady uptake, pointing towards a more grounded support for mother-tongue instruction in some states than others.

Zero Enrolments in Gujarati, Kannada and Malayalam Engineering Courses

Engineering courses introduced in Gujarati, Kannada and Malayalam have struggled to find takers, with many institutions recording zero enrolments over multiple academic years, AICTE stated in the RTI response.

Gujarat Power Engineering and Research Institute launched four engineering courses in Gujarati—Civil, Mechanical, Electrical, and Computer Engineering—with 30 seats each (total 120) in 2022–23.

However, not a single student enrolled in any of these courses in the first year. The trend continued in 2023–24 and 2024–25, leaving all 360 seats vacant over three years.

In Karnataka, SJC Institute of Technology introduced a Civil Engineering course with 30 seats in 2020–21. The course saw zero enrolments for four consecutive years, from 2021–22 to 2024–25.

Similarly, Heemanna Khandre Institute of Technology launched the same course in 2020–21 but failed to attract any students for two years. As per the RTI response, the course has now been discontinued, with zero sanctioned seats. In 2021–22, Maharaja Institute of Technology, Mysore introduced a Mechanical Engineering course and received only one enrolment in four years—during the 2024–25 academic year.

In Kerala, Sreepathy Institute of Management and Technology started Civil and Mechanical Engineering courses in Malayalam in 2023–24 with 30 seats each. No admissions were recorded. The RTI reply showed “nil” under sanctioned seats for both courses in 2024–25, indicating they have likely been discontinued.

Good Response to Telugu and Tamil Engineering Courses

Engineering courses in Tamil have witnessed full enrolment year after year, making it the most successful regional language used to impart engineering education. Encouraged by consistent demand, authorities increased the total number of Tamil-medium engineering seats from 120 to 360 this academic year.

In comparison, engineering colleges offering Telugu-medium programmes have recorded mixed but promising numbers. On average, nearly 50 percent of the available seats in these courses were filled in the last 4 years —indicating a growing interest among students, though not yet matching the success seen in Tamil Nadu.

Mixed Response to Engineering Colleges in Marathi and Hindi

In Maharashtra, Marathi-medium engineering programmes have seen contrasting enrolment trends. The Pimpri Chinchwad College of Engineering (PCCoE) launched a Computer Engineering course in Marathi with an intake capacity of 60 students, and the programme has seen full enrolment across all four academic years—marking it as a success story.

However, not all institutions have been as fortunate. Zeal College of Engineering and Research, which also introduced a Marathi-medium Computer Engineering course, and Dr A. D. Shinde College of Engineering, which launched a Civil Engineering programme in Marathi, recorded zero admissions.

The picture is similarly uneven in Hindi-medium engineering education. Ajay Kumar Garg Engineering College in Uttar Pradesh reported full enrolment for its Hindi-medium Computer Engineering course. In contrast, the Biomedical Engineering course offered in Hindi at the G.S. Institute of Science and Technology failed to attract any students.

e-KUMBH Portal Falls Short on Regional Language Engineering Textbooks

An RTI filed by this reporter seeking details on engineering textbooks translated into regional languages has exposed significant gaps in the government’s efforts to promote technical education in Indian languages.

In its response, AICTE pointed to the e-KUMBH portal—a government-backed platform launched to support the National Education Policy’s vision of higher education in Indian languages.

The portal lists textbooks in 12 languages, including Hindi, Tamil and Gujarati but it fails to provide a single engineering textbook in any regional language beyond the fourth semester.

A deeper look shows glaring shortfalls. For example, only five engineering books are available in Malayalam across all semesters. In most other regional languages, the availability is similarly limited.

Additionally, many of the so-called “translated” books still carry English titles, such as Strength of Materials, Basics of Electrical Engineering, and Fluid Mechanics—even in sections meant for Gujarati readers. This raises concerns about whether meaningful translation has taken place at all.

The findings underscore the challenges in delivering technical education in Indian languages, and cast doubts on how effectively the NEP’s ambitious goals are being implemented on the ground.

VAANI Scheme Struggles Amid Low Budget Allocation: RTI

An RTI filed by this reporter has brought to light the limited financial support provided for promoting technical education in Indian languages under the AICTE’s VAANI scheme.

In response to a query about expenditure over the past five years on translating textbooks and organising events like seminars and workshops, the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) referred to the VAANI scheme—Vibrant Advocacy for Advancement and Nurturing of Indian Languages. The scheme offers financial assistance to AICTE-approved institutions to organise conferences, seminars, and workshops in emerging areas of technical education across 22 Indian languages.

However, the RTI reply shows that the initiative has received minimal financial backing. Over five years, only Rs 2 crore was allocated for VAANI, and actual spending stood at just Rs 1.45 crore—raising concerns about the seriousness of the effort to implement regional language education in technical fields.

The low allocation and underutilisation of funds underscore the growing gap between policy announcements and ground-level execution of the National Education Policy’s goal to promote Indian languages in higher education.

Mother Tongue Best Medium to Educate Children: UNESCO

In its landmark 1953 document “The Use of Vernacular Languages in Education,” UNESCO emphasized the vital role of mother tongues in learning. The report states that the best medium for educating a child is their native language, as it naturally supports both expression and understanding.

Psychologically, it is the language a child processes most instinctively; sociologically, it strengthens their connection with their community; and educationally, it enables faster and more effective learning.

In the Indian context, this insight holds particular significance. According to the 2011 Census, 121 languages are spoken by over 10,000 people across the country. Of these, 22 languages enjoy recognition under the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution as Scheduled Languages.

While the aim to provide technical education in regional languages is a commendable and inclusive step, its effective implementation remains a challenge. It demands substantial resources, institutional capacity, and long-term investment—areas where the current system still falls short.