“We still don’t have a classroom theatre, or a main gate or boundary walls. There’s no infirmary, no 24X7 medical officer deputed on campus, no studio or shooting floors, no website, no logo, no official ID cards, no secure Wi-Fi, no automated power backup. What’s more, we don’t even have a full-time Director on campus.”

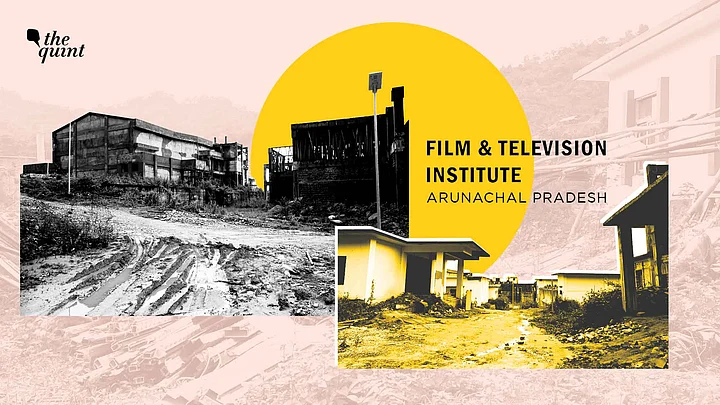

This is the condition of the Film and Television Institute (FTI), Arunachal Pradesh, as described by its first-ever batch of 45 students. It is the third national film institute in India after Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune and Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute (SRFTI), Kolkata.

Located 24 kilometers from the state capital Itanagar, FTI’s foundation stone was laid by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 9 February 2019.

According to the government’s statement, FTI’s construction was approved at an estimated cost of Rs 204 crore and was awarded to the Central Public Works Department (CPWD). It was expected to be completed within 25 months, or March 2021.

Six years later, the institute is far from completion. Yet, the admission process began in August-September 2024 and students were onboarded in March this year, even when nearly 70 percent of the campus is purportedly under construction.

Refusing to “continue learning in conditions that are physically unsafe, emotionally draining, and academically untenable,” the students have called for an indefinite strike until their demands are met.

The Quint looks at how the present condition of FTI Arunachal Pradesh is the polar opposite of what was promised to students and how progress is as little as delays are routine.

Rs 128 Crore Spent; ‘On What?’ Ask Students

FTI, Arunachal Pradesh is a fully funded autonomous institution under the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. It falls under the administration of SRFTI and offers two-year postgraduate diploma courses in Screen Acting, Screenwriting, and Documentary Cinema.

When its foundation stone was laid, the I&B Ministry had promised “a state-of-the-art modern campus” with green features such as a Sewage Treatment Plant, 300 KW solar panels, energy efficient air conditioning plants, street lighting with LED lamps, rainwater harvesting, etc.

As per the ministry’s website, the Institute consists of 21 building blocks, out of which 11 are residential building blocks and 10 academic buildings. It also stated that “the structural work, including civil infrastructure, electric and water supply is almost complete by the CPWD.”

“However, when we came to the campus after a prolonged delay in March this year, we were faced with a different reality altogether. The academic block is not ready, so classes are being held in the library. Hostels weren’t ready either, so we are being put up in the guest house and transit block,” Vishnu* (name changed), a student at FTI, told The Quint.

In the annual report for FY 2023-24, the I&B Ministry stated that CPWD has been engaged for construction work at FTI Arunachal Pradesh and that 82 percent of construction is completed.

According to the annual reports of SRFTI for FY 2019-20 and FY 2022-23:

On 25 August 2016, 52.2 acres of land at Jollang-Rakap village in Arunachal Pradesh was allocated for the construction of FTI

I&B Ministry awarded the construction job to CPWD in March 2019

Construction work started on 8 October 2019 and was then expected to finish by 30 June 2023.

In April 2022, the design of the Open-Air Theatre was finalised

“FTI, Arunachal Pradesh was to be set up at a cost of Rs 128.70 crore. The date of completion was fixed for 7 June 2021, but the work is yet to be completed...only 82 percent of the work is completed,” the auditors noted in the SRFTI’s annual report for FY 2023-24.

According to SRFTI’s website, Rs 189.56 crore was the proposed expenditure for the construction of the FTI. Of this, Rs 128.61 crore—or 67.8 percent —has been spent as of 30 April 2025.

The present condition of the campus then begs the question—where and on what were hundreds of crores spent when after six years the institute is not adequately equipped to handle a batch of 45 students?

According to CPWD's Project Monitoring System, the delays were caused first because of locals' resistance to hand over the land, then because of COVID-19 led lockdowns, no mode of transport, difficult terrain and heavy rainfall.

The Quint has reached out to the I&B Ministry, SRFTI and CPWD with detailed questionnaires. We will update the story once they respond.

Delay After Delay After Delay:

“There was no orientation held explaining the campus’s conditions, the students were kept in the dark till they physically arrived at the location,” Vishnu* told The Quint.

The admission process to FTI started in August 2024 when the entrance exam was held and went on till September for subsequent written and interview rounds. However, for the next five months, there was no clarity on when the classes would begin.

The students wrote to the administration at SRFTI in January 2025, requesting a joining date so that they could make the necessary travel arrangements. On 13 January, SRFTI responded saying nine buildings—including classrooms, library, a daily screening facility, canteen, gym, accommodation with basic amenities—were being readied for Semester-1.

However, when classes finally commenced on 10 March, many of the facilities promised by the authorities were still defunct.

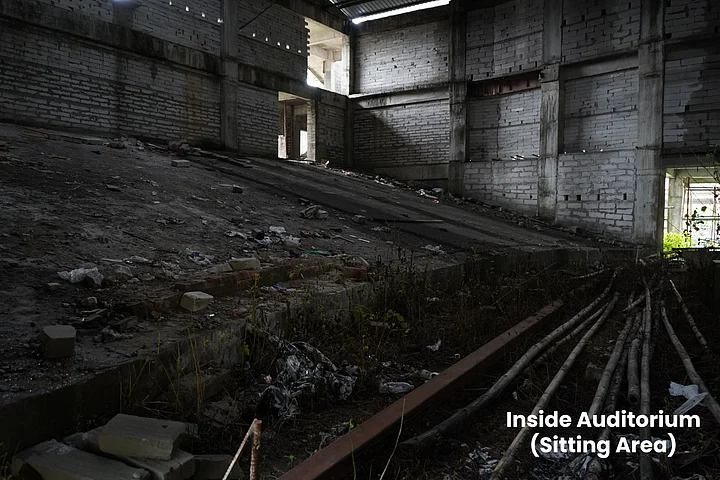

“We were promised highly-specialised courses in filmmaking. Yet we still don’t have a classroom theatre (CRT), where we can screen films. We are having to screen films in the library, which often gets disrupted by power failures. The generator is manually operated; till the time someone switches to power backup, the lecture is over,” Falak* (name changed), a student at FTI, told The Quint.

Besides, there is no performing studio, no sound studio, or auditorium, no gym (which is crucial for students of Acting) and the library has no more than 50 books, Falak* claimed.

'Why Start Admission When Campus Construction Not Complete?'

The students repeatedly wrote to SRFTI, demanding clear timelines as well as an in-person meeting with the Director but to no avail. The students first announced an ‘academic halt’ on 23 March, citing long-standing grievances and repeated administrative inaction.

Two days later, a meeting was arranged between campus Director Jane Namchu and other officials, where the administration promised students that the CRT and a performance studio would be ready by the end of May.

On their demand for a permanent in-campus Director, students were informed that though Namchu was on additional charge, she would be available for all issues related to the campus. She currently holds the position of Additional Director General at Press Information Bureau (East Zone).

Besides, completion of the entire campus was promised by 31 December 2025.

“Why did they start the admission process in August 2024 when the campus was still not complete? How are we expected to learn in this environment,” Falak* asked.

Two Months After Classes Commenced, Still No Facilities

Apart from the gaping holes in the academic infrastructure, basic amenities at the campus are in no better condition.

“Until recently, we were getting muddy water in our taps, which even choked the RO systems. We were relying on cans for drinking water. There is no main gate or boundary wall, raising security concerns. Besides, there are no retaining walls along the hilly road, leading to landslides inside the campus, which will only get worse during Monsoons,” Vishnu claimed.

He added that there were frequent power cuts, with no power on many nights. “The computer lab shuts at around 5:30 pm. With no power at night, how are we expected to finish our assignments?” he remarked.

On 2 May, the students wrote to the I&B Ministry for a full or partial exemption in fee—which is over Rs 1.5 lakh for the first semester, and over Rs 60,000 for subsequent semesters.

FTI Arunachal Pradesh still has no website of its own, no official logo or student email IDs. Stating that they are being “denied the dignity of recognition” students claimed that there still is no official ID card, social media presence, or “any digital proof that we belong to a national institute.”

Falak* added that there was no infirmary at the campus, and that a doctor from the nearest PHC visits the campus twice a week during working hours. “What is one to do in case of an emergency? Snake bites are common here and the nearest hospital is five km away,” he said.

On 15 May, 41 of the total 45 students declared an indefinite strike demanding an immediate solution to these infrastructural challenges. The next day, a meeting was held with the CPWD and the contractor.

When asked to give reasons for the prolonged delay in the completion of the campus, the CPWD allegedly told the students, “The working culture in the North-East is relatively slow. The region is remote; there is a shortage of labour and workers prefer not to stay in such areas. Poor road connectivity further hampers progress.”

Meanwhile the contractor said, “First batch ko toh suffer karna padta hai (The first batch has to suffer).”

Students have now asserted that they will not resume academic activities “until our basic rights as students of a national institution are fulfilled, not merely promised.”