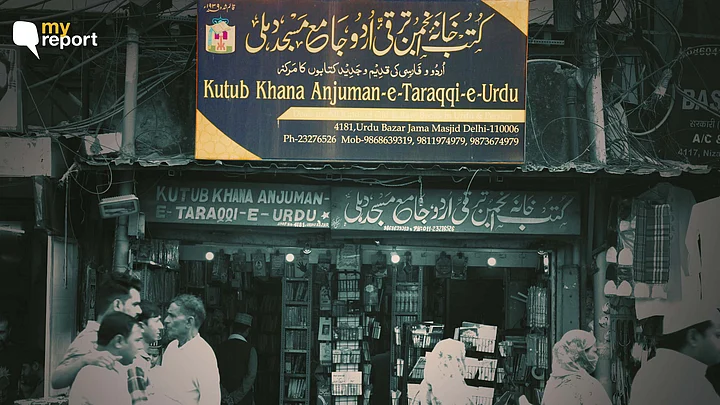

Just opposite gate no.1 of Jama Masjid in Old Delhi lies the long-forgotten Urdu Bazaar. Once a center of Urdu literature, the bazaar today is in ruins.

Barely a few decades back, the market was lined with bookstores, frequently visited by scholars and literature enthusiasts. However, today, only a fraction of the bookstores remains.

'Hardly 4-5 Books Sell in the Entire Day'

Mohammad Mahfooz Alam, the caretaker of Maktaba Jamia, one of the oldest surviving bookstores in the market, laments the growing association of Urdu with a particular section of the population, namely the Muslims, contributing to a decline in interest in Urdu literature. He adds:

"These days, only a few novels, textbooks, and mostly religious books sell. In fact, readers prefer even religious books to be available in Hindi. Business is scarce. On many days, we go without sales, and on others, hardly 4-5 books sell in the entire day."

Maktaba Jamia was established in 1922 as the publishing arm of Jamia Millia Islamia. It was set up with a mission to propagate Urdu, especially among the younger generations, with no commercial intent. Gradually, it transformed into a big publishing house (Maktaba Jamia Limited) known for its publications spanning every genre of literature.

Once a prominent player in Indian Urdu publishing, Maktaba Jamia Limited only has a few its bookstores remaining, including the one at Urdu Bazaar.

The few other bookshops in the bazaar tell a similar story. They are all vestiges of a golden era when book lovers flocked to the bazaar to read and to engage with others with similar literary interests regardless of caste and creed.

"Even 20 years ago, there were many bookshops here, but poor business forced many owners to close their shops and take up other professions. Some of us are still here, hoping that the situation might improve, though the prospects seem increasingly bleak," Alam adds.

'Buying Books Out of Question'

Even Kitab Numa, a famous Risala (Urdu journal) published by Maktaba Jamia Limited, is no longer in regular circulation.

“The present conditions are not very promising. Before COVID-19 many Risale catering to different sections of people were regularly published. However, post the pandemic, most of them ceased publication and now only a few government Risale survive through grants from the state. I used to be the editor of a Risala published by Maktaba Jamia Limited, but I came here once its publication stopped. Evidently, there are not many readers left.”Mohammad Mahfooz Alam, Caretaker, Maktaba Jamia

Eateries now stand where bookshops once flourished, and the love for food has replaced the thirst for Ghalib's and Faiz's poetry. People no longer visit Urdu Bazaar to buy or read books but rather to enjoy kebabs and biryani, say bookstore owners.

Dr Liaqat Ali, a professor of Urdu at Indira Gandhi National Open University, believes that the absence of Urdu as a medium of education in schools – and the consequent ease of younger generations in using English and Hindi – explains the declining readership of Urdu.

“Even if the young people are reading Urdu literature and poetry, they are doing it in Hindi or English,” he explains.

Another reason for the decline of the Urdu Bazaar, according to Dr Ali, is the increasing availability of online versions of books which does away with the need to buy physical copies or visit bookstores, affecting the sale of books.

“The younger generation is so used to having everything at the click of a button that personally visiting bookstores and buying books seems out of the question,” he adds.

Professor Khwaja Mohammad Ekramuddin, an Urdu professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, acknowledges the declining readership and highlights the decentralisation of Urdu publishing.

“While Urdu readership has undoubtedly seen a fall and this is one of the reasons for the decline of the Urdu Bazaar, it is also true that many Urdu publishers can be found scattered across Delhi in places like Daryaganj, Okhla, and Lal Quan. Urdu publishing continues even if readership has decreased to some extent,” he tells me.

(All 'My Report' branded stories are submitted by citizen journalists to The Quint. Though The Quint enquires into the claims/allegations from all parties before publishing, the report and the views expressed above are the citizen journalist's own. The Quint neither endorses, nor is responsible for the same.)