I firmly believe the environment is fundamental to human existence. In the truest sense, our survival depends on nature. Yet, the Rajasthan government is felling khejri trees to clear land for large-scale power projects in the state.

Rajasthan’s state tree, the khejri is indispensable to desert ecosystems. Alongside khejri, other native species such as ber, ker, and rohira play a vital role in sustaining the state’s arid ecology.

A recent study by Anil Chhangani, professor of environmental science at Maharaja Ganga Singh University in Bikaner, revealed that nearly five lakh trees have been cut across the district over the past 14 years—mostly khejri, but also other native species.

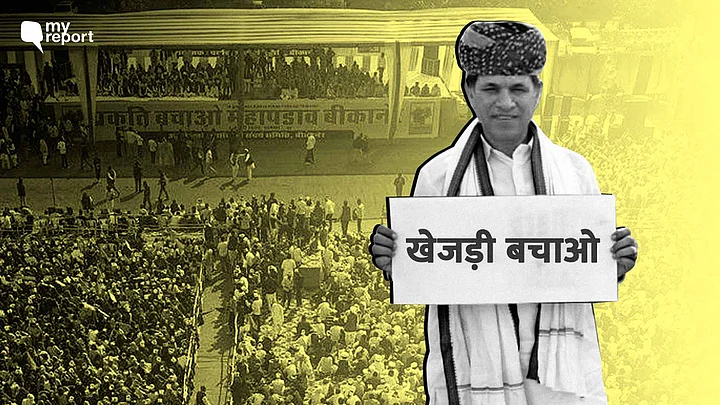

Last week, the members of the Bishnoi community launched Khejri Bachao Andolan in Bikaner. Unsurprisingly, hundreds of protesters gathered, demanding a strong legal framework to protect khejri trees, which they alleged are being cut indiscriminately.

The protest was initially planned as a one-day demonstration on 2 February, Monday. But when the government failed to respond—despite thousands of environmentally conscious citizens assembling at the Government Polytechnic College—we decided to intensify the movement.

The next day, 363 members from the Bishnoi community began a fast unto death, symbolically invoking the historic Khejarli sacrifice. Protesters made it clear that they were prepared to "repeat history" if their demands were not formally acknowledged—and communicated in writing by the government.

‘Saving a Tree Is Worth Even a Life’

It is important to revisit the historic Khejarli sacrifice which took place during the reign of Maharaja Abhay Singh of Jodhpur in Khejarli village in 1730 AD. At the time, the king ordered khejri trees to be cut and burned to produce lime needed for palace construction.

When the king’s men arrived, a woman named Amrita Devi stood in resistance. She hugged a khejri tree to stop the axe and declared—"सर साटे रूंख रहे तो भी सस्तो जाण " (even if a head is cut to save a tree, it is a good bargain.)

Amrita Devi and her three daughters were the first to lay down their lives, followed by other villagers. In all, 363 Bishnoi men, women, and children sacrificed themselves to protect the trees. Shocked by this extraordinary act, the king immediately halted the felling and ordered that no green tree would ever be cut in Bishnoi villages.

I see this incident as one of the earliest environmental movements in world history—proof that community-led conservation existed long before the rise of modern environmentalism.

To understand why an entire community was willing to sacrifice its life for trees—at a time when environmental conservation was not a global concern—we must understand the Bishnoi community itself.

The Bishnoi sect was founded in 1485 AD by Guru Jambheshwar Ji, also known as Jambhoji. The word Bishnoi comes from Bis (20) and Noi (9), referring to the 29 principles laid down by the Guru. These principles combine spiritual discipline, social ethics, and environmental conservation. The key teachings include not cutting trees—especially khejri—protecting blackbuck and chinkara, refraining from killing animals, showing compassion towards all living beings, using clean water, maintaining hygiene, and practising strict vegetarianism.

The community has long embraced a simple and sustainable way of life. Rooted in the harsh ecosystem of the Thar Desert, the Bishnois depended deeply on nature for survival, which explains their reverence for both flora and fauna.

‘Protect All Trees Older Than 50 Years’

On 5 February, Rajasthan Chief Minister Bhajan Lal Sharma told the state Assembly, "I want to assure the people of Rajasthan that we will bring a law to protect the khejri tree, the sacred tree of the state, so that it can be conserved across Rajasthan. The draft of the law will be presented in the Assembly soon."

I want to point out that we are not opposed to development. We have suggested using land along the 1,700-km-long Indira Gandhi Canal, as well as areas along highways and expressways, for solar installations.

These proposals reflect a simple belief: with proper planning and expert consultation, development can move forward without destroying biodiversity.

Development without environmental conservation, however, will ultimately be meaningless. I firmly believe that development and environmental protection are not opposing forces—they can and must coexist.

For this balance to be achieved, the government must take responsibility, involve environmental experts, and adopt genuinely sustainable planning.

As the first step, we demand legal protection for trees older than 50 years—not just khejri, but every species.

We also call for strict accountability of officials responsible for illegal felling and urge the government to issue a clear written circular addressing these concerns.

(The Quint has reached out to the Environment Ministry and Chief Minister's office on the issues raised by the protesting Bishnoi community. Their response is awaited. The story will be updated as and when they respond.)

(The author is a Phd scholar in history from Bikaner.)

(All 'My Report' branded stories are submitted by citizen journalists to The Quint. Though The Quint inquires into the claims/allegations from all parties before publishing, the report and the views expressed above are the citizen journalist's own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)