The most convincing and compelling performance in Santosh Singh’s Aankhon Ki Gustaakhiyan comes from Zain Khan Durrani, whose character (named Abhinav) can most charitably be described as Placeholder Boyfriend. After lead couple Saba (debutante Shanaya Kapoor) and Jahaan (Vikrant Massey) are separated at the midway point, in comes Abhinav.

The screenplay by Singh, Niranjan Iyengar and Mansi Bagla - developed from an idea by Bagla - renders Abhinav at first incredibly understanding, then deliberately mocking, followed once more by the same bland empathy, with all the subtlety of whiplash. But Durrani finds reserves of humanity in this skeleton character and leaves a surprisingly strong impression.

The lead performers remain doggedly committed—even as the plot grows increasingly absurd.

Massey is sweet, although he does nothing he hasn’t before. And Kapoor is particularly impressive - already confident and assured in front of the camera, and keeping you watching even as reasons to stay invested begin to fall away with alarming speed.

Blindness and Dignity

The film takes inspiration from a clever and poignant little short story by Ruskin Bond.

Saba and Jahaan meet, like Bond’s unnamed protagonists, in a train compartment. Jahaan is blind, a fact revealed to us (but not to Saba) in a laughable slow-mo shot where he straightens out his red-tipped stick as the camera takes him in at foot-level.

His blindness is treated with compassion, though: as Saba sanctimoniously declares at one point, ‘blind ko daya naheen, dignity chaahiye’ (the blind need dignity, not pity).

The filmmakers treat it as another aspect of Jahaan’s personality, one they are not shy to talk about, even if he is. It comes up both in direct conversation (‘don’t call me specially abled, it’s like calling the poor specially rich’) and in dumb jokes, like the fact that Jahaan pooh-poohs andh vishwas—blind faith, get it?

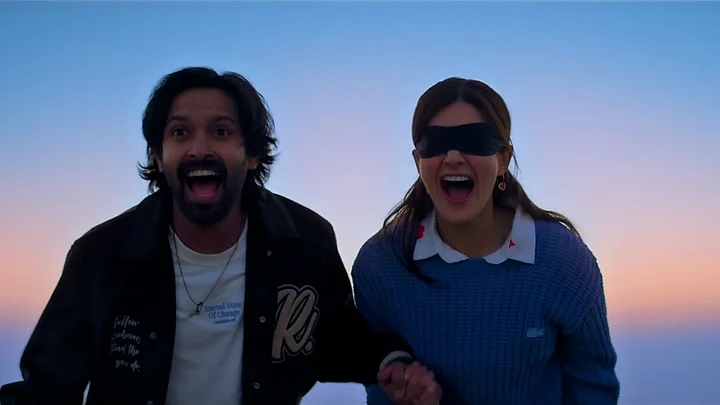

Meanwhile, when they meet, Saba is wearing a patti on her eyes (don’t worry, at least two references to Gandhari are made). Why is she wearing a patti? Oh, she’s an actress, preparing for a… screen test for the role of a blind woman, for which she has donned said patti and decided to spend two weeks in Mussoorie.

So we are primed for a story where vision and its lack is mirrored in both protagonists, just as in the original short story.

Where Love is Blind and So is Logic

But Bagla (also co-producer) pitches a narrative that treats Bond’s story as a mere jumping-off point. The transcontinental screenplay strives to be operatic, but is just plastic, cast in high-Bollywood gloss. This is a style where nothing is real, where no worries that trouble us mere mortals can come in the way of the protagonists’ singular pursuit of love, passion and heartbreak.

For instance, Saba has decided to rock up to Mussoorie without so much as a hotel reservation. Her manager abandons her last-minute. What is this temporarily self-blinded woman going to do? So she latches on to Jahaan, a man she has only just met, whom she hasn’t even clapped eyes on yet.

Poor Jahaan tries gallantly to shake her off, but Saba is one of those only-in-the-movies manic pixie dream girls to whom nothing bad happens even when they willingly fasten themselves to risky situations.

Sure enough, the worst thing Saba has to contend with is a tiny bird flapping around her head. When Jahaan scoffs that she’s scared of a bird, but not of him - a strange man - she retorts, ‘Tum phad-phad naheen kartay’ (you don’t flutter).

For a while, especially in this first half, the movie is passably enjoyable, undeniably foolish but buoyed by butter-smooth visuals (the cinematography is by Tanveer Mir) and a tuneful soundtrack—this is, after all, ‘a Vishal Mishra musical’; I loved the song ‘Yunhi Safar’. Saba and Jahaan inevitably fall in love, kiss and have sex; but they must also confront serious issues… like should Saba take off her patti?

Overripe Melodrama

But once the interval has come and gone, the lovers devastated by separation, and the action now randomly having moved to Europe, we leave the territory of the merely frivolous and enter a dangerous zone of overripe melodrama.

We are abruptly three years in the future, no clue of how we got here or what happened in the interim. A series of crazy contrivances brings our lead pair back together with barely any time for us to have absorbed their separation.

Suddenly, I was reminded of Fanaa - once again a sightless woman who was torn from her lover sees him upon regaining her vision but struggles to recognise him.

The screenwriters lose all control of their material here, particularly in a bizarre sequence where Saba and Jahaan go to a club to talk, only to have and have their drinks spiked, leading to a fuzzy, drug-addled heart-to-heart that drags on endlessly across multiple locations.

In between, Jahaan’s aunt cooks biryani and offers up sage wisdom like, ‘Zaroori nahin train par mila har musaafir same station par utre’ (it’s not necessary that every passenger we meet on a train should alight at the same stop). It’s true, except that she almost instantly instructs Jahaan to go interfere in Saba and Abhinav’s union.

All the niceties in Aankhon Ki Gustaakhiyan—say, the way Vishal Mishra works Saba’s name into a lyric in the song ‘Nazara’, or some of the pretty dialogue phrases, like ‘thithurti sardi’ (freezing cold)—get lost in the preposterous proceedings.

I hope Kapoor and Durrani find better homes for their talents.

(Sahir Avik D'souza is a writer based in Mumbai. His work has been published by Film Companion, TimeOut, The Indian Express, and EPW. He is an editorial assistant at Marg Magazine.)