Films like Kesari Chapter 2: The Untold Story of Jallianwala Bagh are quite an interesting watch, considering the way world politics have been unfolding over the past decade. The film, based on the 2019 book The Case That Shook the Nation, is a dramatic retelling of the events following the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919.

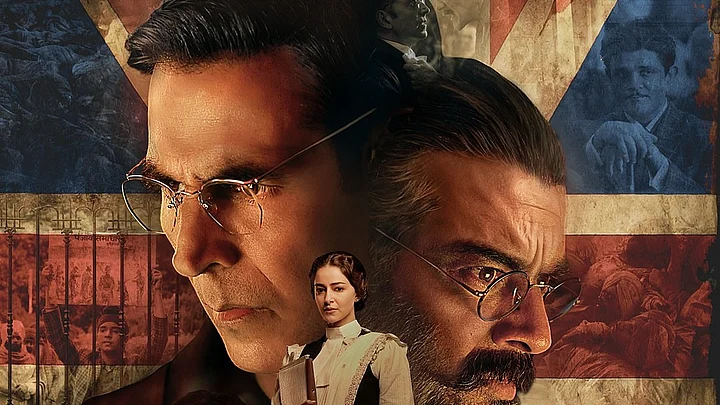

The film’s focus is on one man — Sir C. Sankaran Nair (played by Akshay Kumar), an Indian lawyer who took it upon himself to bring General Reginald Dyer to justice. It’s the kind of film that holds true for its time and for a time much ahead of it — the time in which you & I sit in the theatres.

At its best, and there quite a few bits of it, the film looks into how the British Raj — or more accurately, any oppressive rule — functioned. We see them either control or muzzle the press, bend and exploit the rule of law to suppress dissidents, attempt to label those who lost their lives as ‘violent terrorists’, and use ‘fear’ as a tool to attempt to divide and rule. Kesari Chapter 2 tries to tell the story of standing up against authority, all while being acutely aware of how difficult the battle might be.

For anyone actually listening, the language is hauntingly familiar.

In one particularly telling scene, an ally of the British Raj says, “The thing about the law is that someone is always breaking it; we just need to find out what law Nair is breaking right now.” It speaks to a sombre reality — of the legal and police system sometimes working for those in power even when it is intended to shield the powerless. The language of dissent is enticing to say the least but the issue with Kesari Chapter 2 is that its struggling to find the balance between authenticity of story and the need to be a quintessential Bollywood vehicle — the film isn’t sure about whether it wants the emotions to come from the audience or from the screen.

For a story like this, the right answer would’ve been the former. The film’s first 10 minutes are a recreation of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre — without debate, one of the darkest moments in Indian history — and the scene mostly plays out from the POV of a young Sikh boy who decides to become a physical ‘newspaper’ to act as a living reminder of the tragedy.

Meanwhile Nair’s life is pointedly disconnected from the average Indian — he’s a favourite of the Crown, never having lost a case in his life. Akshay Kumar is both a boon and bane to this film — the actor has a screen presence that can easily overshadow almost everything else.

At the same time, his presence is so looming that he sometimes overshadows Nair — we see Kumar play another version of the actor and the character is lost in the way. That being said, it's still a powerful performance - he embodies the character as a force of nature.

The only hint of Nair being born in Kerala is the inclusion of kalaripayattu and Kathakali in his introduction and perhaps the one line he speaks in his native tongue. That’s primarily also because the film doesn’t ‘write’ Nair as much as it writes a David v Goliath story and tries to fit the character into that mould.

After having watched the film, many would be able to tell you that Nair was a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council and that he was knighted in 1912 (though the film juxtaposes his knighthood with the events of 1919). Moments like these are perhaps why the disclaimer speaks of creative liberty.

One would not, however, be able to tell you that Nair was elected president of the 1897 Indian National Congress and played a crucial role in the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms which increased participation of Indians in the administration in the same year the film is set in. These aspects of his character aren’t just errant footnotes, they would also make his position with the Crown and his later shift in conscience more believable.

But, like I said before, there are quite a few moments of subversive storytelling where the film’s writing tries to push the envelope — lawyers on both sides fight for ‘freedom of speech’ and there are portions where the media exists as a fearsome entity because of their intent to publish the truth.

Even the mention of a show of Hindu-Muslim unity acting as a threat to the British Raj, especially to their idea of ‘divide and rule’ is particularly clever.

Kesari Chapter 2 isn’t a film that exists in the finer points or the subtext — it’s telling is too grand and sometimes too rushed to actually let these finer points sink in. For instance, when a British woman accuses her partner of sexual violence and it is proved false in court — there was laughter in the theatre. It became a ‘gotcha’ moment though I’m not sure for whom.

The implication of how violence against women can be twisted for political and social gain, all while placing women on the backfoot with no actual progress when it comes to their emancipation and safety is lost by the time the scene plays out on screen.

The film is too focused on a black-and-white win and lose narrative to try and understand the more complex aspects of its story. Granted the film can’t be held solely responsible for this but a more nuanced approach to the story would’ve done wonders for what is already quite a watchable film.

This is partly because almost every character we see on screen does their part — from Regina Cassandra’s memorable turn as Lady Nair to perhaps what is Ananya Panday’s most impressively restrained performance (as a young female lawyer who becomes Nair’s first push of conscience) to R Madhavan’s brooding and eyeball-grabbing entry in the second half.

Simon Paisley Day as Dyer paints an imposing and frustratingly devious figure and, despite the one-dimensional writing his character gets, the actor does his absolute best to bring Dyer to life.

Debojeet Ray’s cinematography and Nitin Baid’s editing also deserve credit for how the film turned out — when the film understands the importance of balancing what needs to be shown and what needs to be implied, it leads to quite an impressive visual result.

The background score, while sparingly effective, mostly seems forced into the narrative. The film's songs, however, are better suited with 'Kithe Gaya Tu Saaiyaan' being the obvious standout.

The film’s first half is far superior than the second, which is held together mostly by Kumar and Madhavan sparring against each other and one particularly rousing sequence where Nair’s motives for acting out in court become clear. The language, though intended to work for a massy audience, does sometimes end up feeling out of place in a film from the 1900s.

The film’s end plates mention Sardhar Udham, the revolutionary portrayed by Vicky Kaushal in Shoojit Sircar’s film. One can’t help but compare — there was a raw, sincerity to that film that Kesari Chapter 2 just can’t capture.

And yet, it’s not exactly a futile exercise — there is a story, a lesson, somewhere in there for those actually listening. And for those who stopped listening years ago, it’ll at least be an impressive spectacle and perhaps do enough to jostle the conscience.