From coastal villages to forest heartlands, The Quint is telling the full story of how climate change is reshaping lives and ecosystems in India. Help us do more. Become a member.

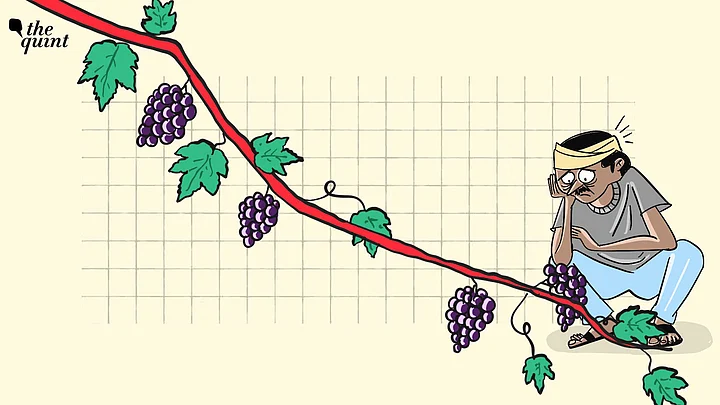

"This is the first time I’ve seen such unrelenting heavy rains during summers in this region," says Sandip Jagpat, a grape cultivator of over 20 years in Nashik, a town in Maharashtra often referred to as India’s wine capital.

From planting and nurturing to pruning and harvesting, his work is deeply tied to winemaking. But with erratic rain patterns disrupting the process, he’s uncertain whether the next harvest in March-April 2026 will bear any fruit at all.

"Since the first week of May, it rained continuously for almost three weeks. It started right after the pruning season in April, when we prepare the grapevines for the next crop. Our harvest could be in danger, but we just have to wait to see how bad the damage will be,” he laments.

As extreme weather events become more frequent, their effects can make or break an entire harvest of grapes, considered to be a “delicate” crop.

'Our Grapes Are in Danger'

"Grapes are a really sensitive crop so the impact of climate change is seen very strongly," Subhash Katkar, District Superintending Agriculture Officer, Nashik, tells The Quint.

"Extreme heat, extreme sudden temperature drop, unseasonal rain, and even a stark difference in day and night temperature impact the grape crops."Subhash Katkar

This year, the unseasonal rains in May drenched the new shoots before they had a chance to strengthen.

“We especially need a dry spell between May and June,” explains Jagpat. “But now we’re getting summer monsoons instead.”

"If they don’t fruit next year," he adds, "I lose the money I spent this year—and then, I’ll have to spend again to start all over."

Jagpat, who cultivates grapes on two acres of land, explains that it costs between Rs 1 lakh and Rs 1.5 lakh per acre each year. In a good season, the harvest can bring in returns of Rs 4-5 lakh.

But by next year, he estimates his total loss could reach Rs 6 lakh — including the Rs 3 lakh he’s already invested, which would be entirely lost, and another Rs 3 lakh he’ll need to reinvest to restart the process for the 2027 harvest.

Vilas Dargude, another grape cultivator in the region, says the estimated loss from grape cultivation could hit him even harder, given the setbacks he has already faced this year.

"I also grow onions, and nearly two-thirds of the crop rotted due to unseasonal rains just before harvest in April," he says. "If we don’t earn enough from the grapes next year, it will be really difficult to invest in its next cropping cycle."

While there are schemes like the Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (WBCIS) and the Maharashtra Project for Climate Resilient Agriculture by the state government to protect against losses such as this, both Jagpat and Dargude say they haven't been able to avail them as the damage isn't visible yet.

Subhash Katkar confirms this, saying,

"For farmers, we have tried to protect them to some extent with the crop insurance scheme. But since the damage is not clear yet and will only be known next year, it will take time to avail."

The Trickle Down Impact on Wine

Larger commercial players like Rajeev Samant, CEO of Sula Vineyards Limited, one of India’s largest wine producers, also echo this sentiment.

Samant explains that his company primarily works with two kinds of grapes—wine grapes, used for the more expensive wine, and table grapes, which are consumed fresh and also used in the production of more affordable wines. "We can see the impact on both kinds of grapes," he says.

"In terms of table grapes, we’ve noticed that yields are becoming increasingly erratic due to unseasonal rainfall," he says.

One consequence of the reduced yield has been a sharp rise in prices.

"When the yield goes down, the prices immediately spike up in the market," he explains. "Prices were much higher than usual in May and June. It was up to 50 percent higher than normal this year as far as table grapes go. So, grapes that were normally going for Rs 15 per kg shot up to Rs 25 per kg approximately."

Samant adds that what’s truly concerning is that this isn’t just a one-off weather event, it’s becoming the new normal.

"This used to be rare. Now, we’re seeing a 20-25 percent drop in yield almost every other year due to unseasonal downpours.”Rajeev Samant, CEO of Sula Vineyards

It’s not the rain alone. Even when there’s a dry spell, rising temperatures in late March and April are becoming an equally serious concern.

Traditionally, harvests continued into mid-April, but now wine producers and vineyards like Sula finish picking their grapes by the end of March to avoid what Samant calls “grape collapse”, a condition where berries lose weight, acidity drops, and the wine ends up tasting flat.

Beyond reducing overall yield, erratic weather, particularly prolonged periods of extreme heat and humidity, also affects the quality of the grapes. Rising temperatures can cause berry size to shrink and bunch weight to decrease, resulting in lower output, especially for table grapes.

Aesthetics, while a seemingly minor concern, play a critical role in determining market value, particularly in exports, explains Samant.

"Extreme heat can cause the berries to crack and scar. Those grapes are downgraded in the market and often disqualified from exports."Rajeev Samant

Moisture retention is another growing concern. Grapes exposed to untimely rain can begin to leak during transit, a flaw international buyers won’t tolerate.

According to the Economic Survey 2024-25, India exported over 3.4 lakh tonnes of fresh grapes worth Rs 3,460 crore in 2023-24, with Maharashtra contributing more than 67 percent of the total output.

In Nashik alone, around 18,900 hectares have been registered for export-grade grape cultivation.

Grape exports from Nashik declined by 25 percent during January-February this year compared to the same period in 2023, according to the state agriculture department.

“For exports, the quality has to be consistent. When it rains at the wrong time in the season, it severely impacts the crop — growers can’t guarantee quality,” says Samant. “Exporters of table grapes are increasingly worried as such weather events become more frequent. Both export volumes and prices are likely to take a hit.”

What’s At Stake?

The twin shocks of erratic rainfall and intensifying heat are warping both ends of the grape supply chain.

For Nashik’s farmers and vintners, the message is clear: the seasons are no longer dependable.

“What we’re seeing now is extremes,” Samant says. “You don’t just get a little more rain—you get an entire month’s rainfall in a single day. Then nothing for weeks. That kind of variability is the hardest thing to deal with.”

In response, producers are slowly shifting to heat-tolerant varieties and pruning earlier in the season. But these adaptations can be costly and have limited impact.

“If there’s more humidity, there’s more mildew,” Samant explains. “You need more pesticide sprays which are expensive. This also means more labour.”

For small farmers like Jagpat, these extra costs arrive without guarantees.

"This isn’t just a localised issue, it’s part of the larger problem of global warming. Similar impacts are being seen in agriculture everywhere," says Katkar.

And he’s right. Climate change, once seen as a distant global crisis, is now revealing itself through agricultural damage in direct and tangible ways.