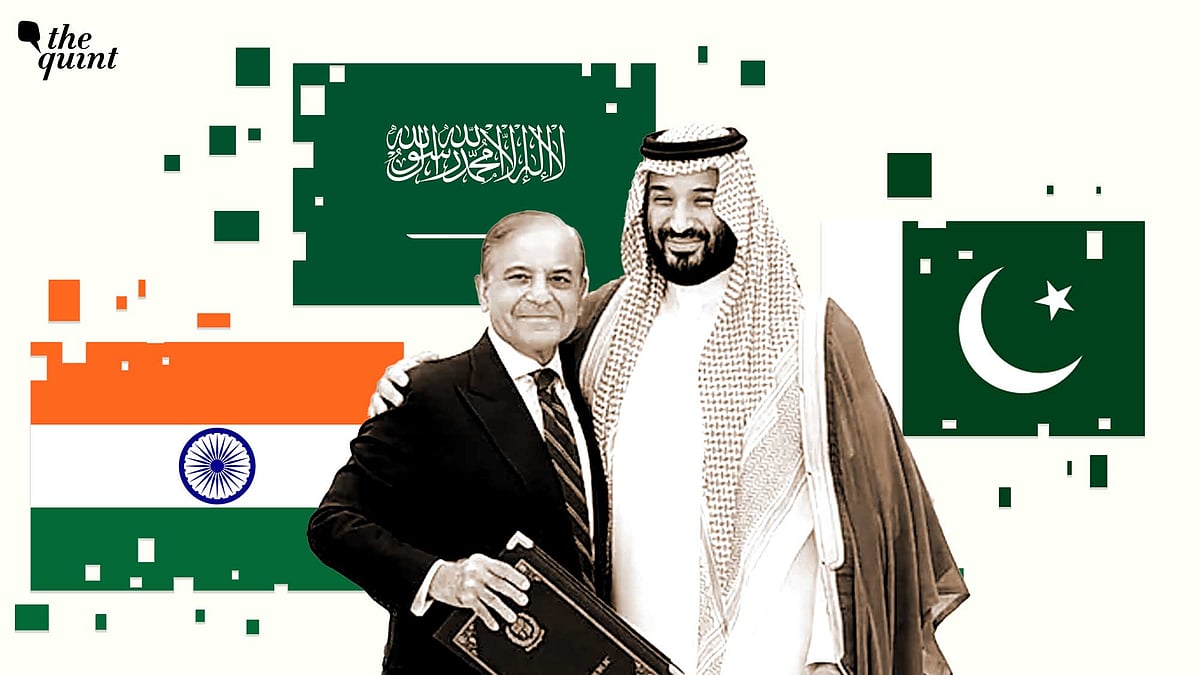

Saudi–Pakistan's NATO-Style Defence Pact Raises New Nuclear Concerns for India

The Saudi-Pak relationship enjoys American support as it pressurises Iran while drawing Pakistan away from China.

advertisement

On 17 September, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan signed a “Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement” during Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s visit to Riyadh.

This was Sharif’s third visit to the Gulf nations in a week, after the 9 September Israeli strike on Hamas in Doha. The pact contains a NATO Article-5 type declaration, ie, “An attack on one will be treated as an attack on both.”

The next day, Pakistan’s Defence Minister KM Asif, while underscoring the nearly eight-decades-old Saudi-Pakistan military ties, added that Pakistan’s nuclear programme will be made available to Saudi Arabia if needed under this agreement: "We have no intention of using this pact for any aggression, but if the parties are threatened …this arrangement will become operative."

He also suggested that the pact could be extended to other Gulf nations. Although no further details stand revealed, it “encompasses all military means”, perhaps implying conventional military forces, nuclear cooperation, and intelligence sharing.

However, India has less to worry from the pact’s NATO Article-5 type declaration, though the statement on nuclear programme should raise concerns on regional security, even as the pact impinges on broader Indian interests.

Fallout of Israel's Strike

In the Middle-East and Levant, schisms are not limited to just Sunni-Shia divides, but can be further divided into the following camps:

The Saudi-led Arab camp (including Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE, Egypt)

The Iran-led Shi’ite camp (Iran, parts of Iraq and Syria; Houthi-controlled Yemen)

The non-Arab nations on the periphery (Turkey, Pakistan)

The battlegrounds of Syria and Yemen, with Israel and the US being the main attackers.

Although the Gulf Cooperation Council members possess a fair amount of cutting-edge military equipment, they neither have the requisite trained manpower, nor the capacity to fight modern wars. Hence, they have traditionally been dependent on the US for primary deterrence.

While the US’ response to the Arab Spring, Obama’s Iran nuclear deal, the 2019 attacks on Saudi Aramco, 2022 Houthi strikes on Abu Dhabi, and Israel’s degradation of Gaza, had progressively eroded confidence in that dependency, the strike by a US ally on Doha—and subsequent statements by Washington—have left Qatar (and others) questioning why the US air defence systems in Doha failed, and the authenticity of US security guarantees.

Notably, Qatar, which hosts the US’ largest air base outside its own territory at Al-Udeid, was designated a Major Non-NATO Ally in 2022.

The strike has therefore not only escalated regional tensions but also rattled the Gulf nations, presenting them with a new security predicament. They are thus seeking greater unity, coordination, and diversification of security guarantors.

On 10 September, the UAE President Mohammed bin Zayed visited Doha, and along-with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, condemned Israel’s “brutal aggression” against Qatar; the latter vowed that Riyadh would stand with Doha “without limit.”

The Arab League and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation also condemned, on 15 September, the Israeli strike—even as the US Secretary of State Marco Rubio visited Doha in a bid to repair the damage.

Pakistan-Saudi Relationship

The Pakistan-Saudi relationship has been close as well as problematic. While the Saudis have enough money to buy the latest weaponry, a gap has persisted between procurement and capability.

Fearing a coup, Saudi military personnel usually aren’t imparted good training. This, combined with the institutional weaknesses typical in authoritarian monarchies (“not national armies but the armies of ruling families”) led to Pakistan stepping in.

In early-1970s, Pakistan expanded this to technical cooperation on civil aviation, as well as building fortifications along the Saudi-Yemen border. The Pakistani military’s engagement gained traction after its troops participated in the 1979 operation to neutralise extremists who had seized the Grand Mosque, Mecca.

This was followed by the Saudi-Pak-US cooperation on waging a ‘jihad’ in Afghanistan against the Soviets. The ensuing regional turbulence saw both nations signing the “Deputation of Pakistani Armed Personnel and Military Training” in 1982. This established the Saudi-Pakistan Armed Forces Organisation and led to the peak deployment of 20,000 Pakistani troops in Saudi Arabia.

During the 1991 Gulf War, Pakistan deployed over 11,000 troops to protect Saudi borders and holy sites. Post 9/11, both nations reinforced military and intelligence cooperation. Ex-Pak Army chiefs, General Raheel Sharif and General Qamar Bajwa, have commanded the Saudi-led Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition.

The US had encouraged the Saudi-Pakistan relationship as it not only pressurised Iran, but also drew Pakistan away from China. In 2015, however, Pakistan declined to provide ships, combat-aircraft, and troops for the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen against Iranian-allied Houthi rebels.

Nuclear Dynamics

In 2008, US-Saudi Arabia signed an MoU for an intent to cooperate on nuclear activities in the fields of medicine, industry, and electricity production. In July 2017, Saudi Arabia approved a National Project for Atomic Energy, including plans to build nuclear reactors for electricity production and sea-water desalination.

Between 2015-2017, it signed agreements with Russia, France, and South Korea on small reactors, and with Kazakhstan on nuclear fuel. In September 2018, the US proposed a “123 Agreement” but only if the Saudis forswore enrichment and reprocessing. However, the US has not finalised any agreement. In June 2023, the Saudi Foreign Minister stated that while they would prefer to be have the US as one of the bidders, it wanted to build its nuclear programme with the best technology in the world – and as of July 2024, companies from China, France, South Korea, and Russia were approved bidders.

Saudi Arabia has long been linked to Pakistan's nuclear weapons programme. Pakistan’s Brigadier, Feroz Hassan Khan, is on record outlining Saudi Arabia’s “generous financial support to Pakistan that enabled the nuclear programme to continue, especially when under sanctions.”

In 1999, then Saudi Defence Minister Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz visited Pakistan’s nuclear installations, and reportedly, Pakistan offered to ‘loan’ nuclear weapon(s) to it if Iran went nuclear. In March 2018 and Sept 2023, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman stated that if Iran were to obtain a nuclear weapon, the Kingdom "will follow suit.” Thus, the nuclear signalling through Pakistan, the only Muslim-nation with nuclear weapons, is primarily meant for Israel (Middle East’s sole nuclear-armed nation), and Iran.

Implications for India

With Pakistan’s strategic utility to the US declining after the latter’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, the pact strengthens the long-standing Pakistan-Saudi relationship, with the former enabling security and latter providing money. Given traditional Saudi generosity, Pakistan may now be able to provide bit more funds to its scrawny defence budget.

Saudi Arabia seeks protection against Iran and Israel through this pact’s “joint deterrence shield,” while Pakistan looks to deter India. But drawing a line in the sand is one thing, enforcing that line is another. The US didn’t come to Pakistan aid in 1965 or 1971 despite the Mutual Defence Assistance Agreement (1954) or SEATO/CENTO, nor did China pro-actively assist its ‘all-weather friend’ in 1999. Thus, the pact should be construed for what it is: a political signal of solidarity and strategic cooperation.

The US decision to revoke the sanctions waiver on Iran’s Chabahar Port, effective 29 September 2025, will also cast a shadow over India’s carefully nurtured regional connectivity strategy. And if the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) construes that the US is an unreliable security provider, the latter may find itself pushed away, to the strategic benefit of China.

(The author Singh is a retired Brigadier from the Indian Army. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined