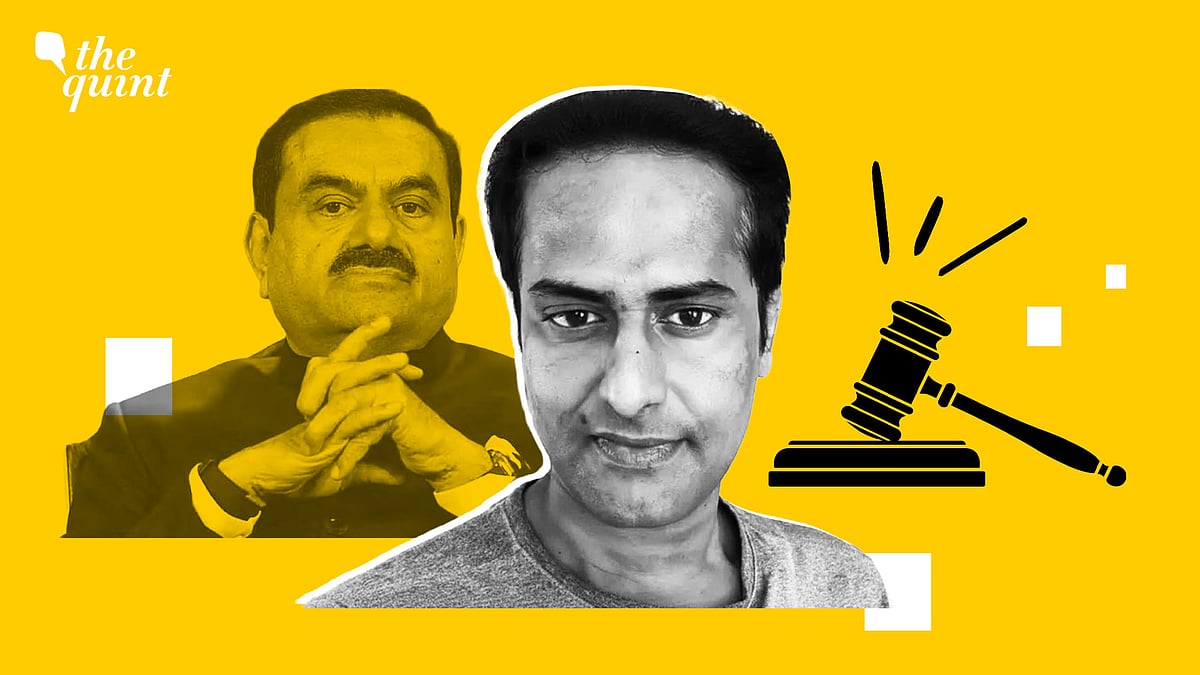

Journalist Ravi Nair vs Adani: When Courts Turn Critics into 'Criminals'

Criminal defamation now functions as a pressure tool. Reputation matters, but can it be a shield for accountability?

advertisement

Let me say this plainly.

This judgment is not just about one man and a few tweets. It is about how power responds to criticism. It is about how criminal law is increasingly used to manage dissent. And, it is about the quiet fear that settles over journalists when prosecution signals more than it says by becoming the price of asking hard questions.

In Adani Enterprises Limited v Ravi Nair, the Magistrate’s Court in Mansa, Gujarat, convicted the accused for criminal defamation based on tweets and articles that questioned the relationship between the Adani Group and the Central government.

Yet, the court treated the criticism as criminal. The law protects reputation. No one disputes that. But when a large corporate conglomerate invokes criminal process against a critic for speaking on public affairs, courts must move carefully. In this case, they did not.

When Criticism of Corporate Groups Becomes Crime

The defence argued that the tweets referred to the “Adani Group,” not specifically to Adani Enterprises Limited. The court held that imputations against a collection of persons can amount to defamation of a company. That reading of Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code may be technically correct. But, it ignores context.

If every reference to a business group allows any constituent company to initiate criminal prosecution, criticism becomes legally hazardous. The larger and more powerful the group, the wider the net of liability. That does not strengthen democracy. It weakens it.

Jurisdiction Anywhere, Prosecution Everywhere

The court upheld jurisdiction because the complainant’s representative claimed to have read the tweets while present in Mansa.

In the age of the internet, that logic stretches infinitely. A tweet is accessible in every district of India. If access creates jurisdiction, then every district court can summon the speaker.

The process itself becomes punishment. The accused must travel. He must seek bail. He must appear repeatedly. Years pass. Many journalists do not have the resources to fight cases in distant courts.

The message spreads quickly: speak carefully, or prepare for litigation. That is how chilling effects operate. Quietly. Systematically.

The Burden Shifts in Practice

The court accepted the electronic evidence and noted that the accused did not dispute authorship of the Twitter (now X) handle. That may satisfy evidentiary rules. But, criminal defamation requires more than authorship. It requires proof of intention to harm reputation. In cases involving public debate, courts must distinguish between sharp criticism and malicious falsehood.

That approach risks shifting the burden. The critic must now prove his innocence rather than the complainant proving criminal intent. That inversion is dangerous.

The Gujarat Context Cannot Be Ignored

This judgment does not stand alone. In 2023, a Gujarat trial court sentenced Rahul Gandhi to two years’ imprisonment for remarks concerning the surname “Modi.” The Gujarat High Court affirmed the conviction. Only when the matter reached the Supreme Court of India was the sentence stayed.

That two-year sentence was not incidental. It triggered immediate disqualification from Parliament. Criminal defamation moved from the margins of penal law to the centre of constitutional consequence. The present case reflects the same judicial instinct. Use the maximum force of criminal law to respond to speech. Even when the speaker is not a Member of Parliament, the signal remains. Criticism carries risk.

The Problem With Criminal Defamation

The Supreme Court upheld criminal defamation in Subramanian Swamy vs Union of India. But even that judgment emphasised balance. In practice, the balance has tilted.

Criminal defamation complaints now function as pressure tools. They consume time and money. They exhaust defendants. They deter future speech. Acquittal after years of trial offers little consolation. The Mansa judgment reinforces that pattern. It does not ask whether the tweets addressed matters of public importance.

It does not examine whether the speech constituted opinion, rhetorical critique, or investigative commentary. It focuses instead on the absence of a successfully proved statutory exception. That narrow approach reduces constitutional free speech to a technical defence.

A Contrast From Across the Ocean

The US Supreme Court confronted similar tensions in New York Times Co vs Sullivan. It held that public officials must prove actual malice. They must show that the speaker knew the statement was false or acted with reckless disregard for truth.

The court understood that debate on public issues will include errors. It chose to protect debate rather than punish imperfection. India has not adopted the actual malice standard. But we share the same democratic aspiration. Public affairs demand open criticism.

Reputation, Power vs Human Cost

Behind every such case stands an individual. A journalist. A commentator. A citizen with a social media account. He receives a summons. He hires counsel. He travels to court. The case stretches for years. Each appearance costs time and money. Each adjournment prolongs uncertainty. Others watch. They calculate. They decide what not to write.That is the true chilling effect. It does not require prison bars. It only requires credible threat.

They must demand clear proof of malicious falsehood. They must guard against forum shopping. They must resist turning dissent into crime.

The stay granted by the Supreme Court in Rahul Gandhi’s case served as a reminder that criminal law must not be deployed casually in matters of speech. This judgment moves in the opposite direction. If such reasoning hardens into precedent, journalists will not be jailed in large numbers. They will simply fall silent. A democracy rarely collapses overnight. It contracts, case by case, order by order. This judgment is one such contraction.

(Sanjay Hegde is a senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)