When a Military Strike is Righteous, Just, and Accompanied With Right Conduct

Revenge can be personal but punishment essentially serves a societal function, writes Lt Gen Bhopinder Singh (retd).

advertisement

Whenever soldiers of a moral nation go to war, they are expected to have complied with two criteria—jus ad bellum ('Right to go to war') and jus in bello ('Right conduct in war').

Professional militaries of a participative democracy like India do not exert a political decision on their own. For example, conduct or direct cross-border operations without the explicit approval of the civilian government. This is unlike a quasi-democracy like Pakistan where the proverbial ‘establishment’ (Pakistan military) is a widely acknowledged as a 'State within a State'.

A Justified Operation

Even Bhagavad Gita—as among the most revered scriptures and treatises of this ancient land—propounds on the essential Dharma (duty or ethic) of a noble warrior to wage war in a situation of Dharamyuddha (righteous war).

Verse 7, Chapter 2 notes: “If you are killed you shall reach heaven; or if you triumph, you shall enjoy the earth; so stand up Son of Kunti, firm in your resolve, to fight!”

It goes on to posit, “The one who thus restrains the self, and who governs the self, attains peace”. In modern context, this lesson from Gita can also be interpreted as an anti-scorched earth approach.

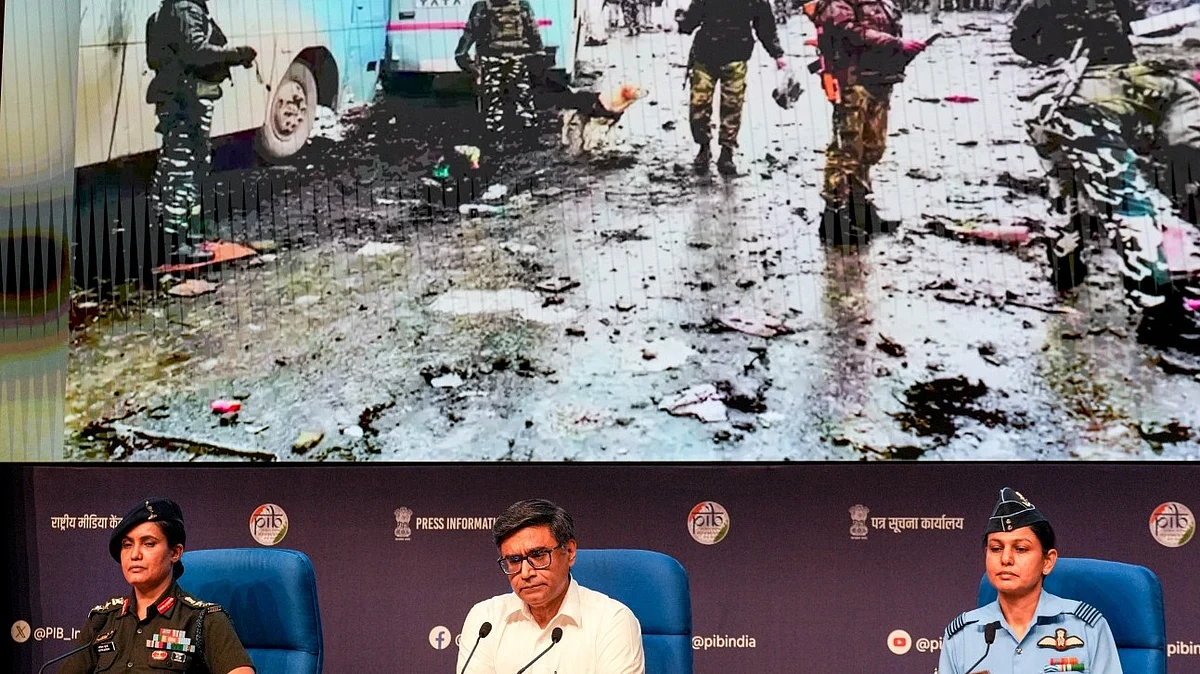

So did the Indian military’s recent retaliation—Operation Sindoor—at nine locations: Four in Pakistan and five in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK) fit the bill of “a just war”. Unequivocal short answer, yes.

This recent action by the Indian military also recognises the reality and necessity of getting forced into taking up arms as embedded in the Gita by not valourising violence (in fact it is against those who perpetuated violence in the first place)—and instead reposing faith in the principles of justness and fairness, with the ingrained intent that the chances of violence going forward, diminish.

Punishment, Not Revenge

Viewed conversely from the prism of the terrorists supported by the other side, the Pahalgam terror attack was a case of a perfectly opposite instinct and ignoble intent. Pahalgam was not conducted by the military of the other side but by an amoral and illegitimate authority (read, terrorists), in an unjust setting, with unfair means.

For that side to equate the Indian reaction as a tit-for-tat is wrong, given the diametrically opposite intent, purpose, and underpinnings involved. Unlike the actions of terrorists in Pahalgam, the Indian counter-reaction essentially sought to protect the dignity of a nation and its people, restore imperatives for peace, and even ensure human rights.

Punishment sets the expectation of a guaranteed price (retaliation) onto a group of people or the state that they represent, due to their malintent. That this price (in this case cross-border attacks at nine sites) is by its very nature, painful, humiliating and extracting in expression and outcome, is a fact and a necessity.

A part of national and ethical narrative expected of a moral State is also to guarantee its citizens justice in the form redressed means against a conventional or even an asymmetric ‘enemy’ like Pahalgam terrorist and their benefactors across the LoC (Line of Control).

Militaristic reactions against perceived wrongs do not have to suffer any moral dilemma. On the contrary, inaction can erode foundations of righteousness and duty that is freighted on any government in charge of its people.

India an Emerging Power to be Reckoned With

Those who undertake violence on behalf of the nation, i.e. professional soldiers, are deeply trained and versed in the concept of always “doing the right thing” with the assumption of inviolable character and ethos. Their action (or violence) can never be equated to the barbaric and cowardly actions of the terrorists who undertook the Pahalgam attack.

Through their disciplined, kinetic, and thought-through retaliatory action the Indian military has not just satisfied the collective conscience of a wounded nation but earned its trust to protect its citizen as can be expected of a responsible and just “sword arm” of the nation.

Implicit belief in just-war is the functional equation besetting the infliction of punishment:

(Probability of deterrer carrying out deterrent threat X Costs if threat carried out) > (Probability of the attacker accomplishing the action X Benefits of the action)

While the ultimate outcomes may or may not stay true to this equation – clearly, “taking no action” by a responsible State when faced with situations like the horrific Pahalgam attack, is simply not an option.

This counterattack has defined India’s expected behaviour in future conflicts or suchlike security exigencies. It is in line with military theorist Patrick Morgan’s observation, “The threat to use force in response as a way of preventing the first use of force by someone else”, is obvious in this recent Indian reaction.

Seen from various prisms, be it civilisational, moral, ethical, professional or its more evolutionary form of realpolitik, this counterattack as undertaken by India is legitimate and supported by defendable rationale. Pakistan has presumably misread (or failed to manage underlying conditions within its control) the reaction from India and cannot persist with its dated “bleed with a thousand cuts” approach, as much water has flowed (even as it is increasingly sought to be stalled now) through Indian rivers into Pakistan for it to continue playing with the old playbook. Bravo-Zulu Indian Military!

(The author is a Former Lt Governor of Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Puducherry. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined