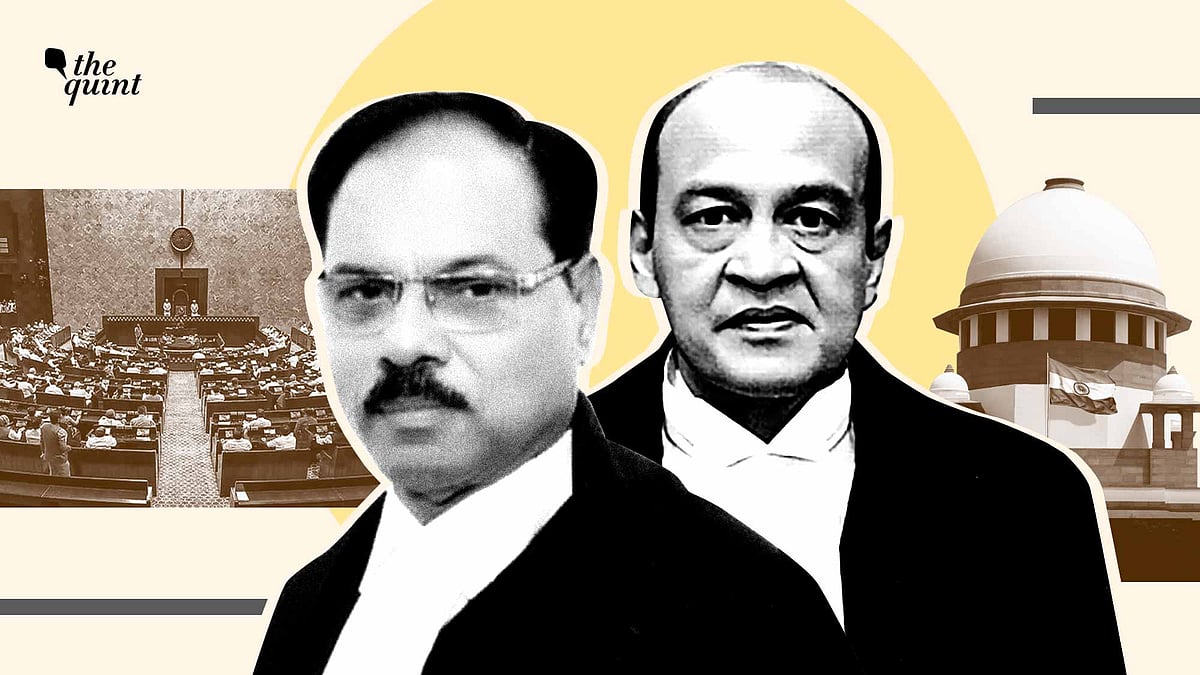

Justice Yadav vs Justice Varma: When Politics Decides Who's Saved and Who's Not

Justice Yadav’s misconduct may or may not be defensible. That's for the inquiry to determine, writes Sanjay Hegde.

advertisement

In recent months, an affair of quiet consequence has unfolded within the judiciary—one that speaks less about an individual judge and more about the institutional balance of power between the courts and the political class.

The Justice Shekhar Kumar Yadav episode is no longer just about communal remarks at a public event. It is now about whether the Supreme Court of India retains the authority to discipline its own, or whether it must first seek clearance from those in high political office.

Let us be clear. When a sitting judge of a constitutional court speaks at a platform hosted by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and makes comments that are—by all accounts—communal and provocative, the matter cannot be brushed aside as mere indiscretion.

That inquiry, however, never quite took off. The in-house mechanism of the Supreme Court, which has previously handled sensitive matters with measured efficiency, was asked to pause in February this year, on the basis of a letter from the Rajya Sabha Secretariat, purportedly under instructions from the Vice President.

The letter claimed that since an impeachment motion had been moved in Parliament, the judiciary must stand down. That motion, signed by 55 Opposition MPs, has since languished, ostensibly under “signature verification,” for over six months.

Contrast this with the case of Justice Yashwant Varma.

Kapil Sibal, one of the signatories to the impeachment motion against Justice Yadav, rightly points out that in that case, no such letter was sent, no pause was requested, and no political hand reached out to shield the judge from scrutiny. The processes of the court were allowed to proceed unimpeded.

The Judiciary’s Domain Must Be Its Own

Let us remind ourselves that the independence of the judiciary is not merely a principle of governance. It is a structural necessity.

Just as the military must be free from political interference in its internal appointments, promotions, and disciplinary actions, the judiciary too must have absolute authority over its personnel. If judges are to be independent in their decisions, they must also be subject to internal discipline free from political interference.

Let us also not forget: an impeachment motion is only the start of a long process. The Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, contemplates a proper inquiry to be set up under the Act before any impeachment can proceed meaningfully.

Sibal has pointed out that in some cases, such as Justice Varma’s, the government appeared in undue haste to move ahead without such an inquiry, suggesting that procedural rectitude is selectively applied.

Creeping Control: A Clear and Present Danger

We must not look away from what is happening.

The Supreme Court has, over decades, painstakingly built its independence. The collegium system—however flawed—was meant to ensure that the selection and regulation of judges remain within the judiciary’s domain. But collegium authority means little if it cannot even decide whether a sitting judge should continue to hear cases while under a cloud.

By allowing the Vice President’s letter to derail its in-house process, the court has allowed a dangerous precedent to take root. If this goes unchallenged, future political actors will know precisely what to do when a judge inconvenient to their cause becomes a problem—send a letter, move a motion, and sit on it.

And what becomes of judicial accountability, in the meantime?

A Call for Institutional Clarity

The moment has come for the judiciary to draw a clear line. The Supreme Court must state unambiguously that its in-house mechanisms are not to be paused, suspended, or subjugated to political processes.

The larger message must be clear: just as the judiciary does not interfere with the functioning of Parliament or the Executive, it expects the same courtesy in return. Each institution must operate within its sphere. Parliamentary impeachment and judicial inquiries are not mutually exclusive; they are complementary, each with a distinct purpose and procedure.

The notion that one must stop because the other is pending is neither constitutionally mandated nor logically sustainable. The judiciary must reaffirm this boundary—firmly, clearly, and immediately.

Reclaiming Lost Ground

Justice Yadav’s misconduct may or may not be defensible. That is for the inquiry to determine. But what is already apparent is that the manner in which the process has been stymied sends all the wrong signals.

This must not be allowed to stand.

The judiciary must reclaim its control over appointments, transfers, and disciplinary mechanisms. The Supreme Court’s authority is being tested—not with loud confrontation, but with soft, strategic encroachments. These are the more dangerous kind, for they come dressed in procedure and wrapped in delay.

It is time for the judiciary to push back. And it must start by ensuring that no judicial work is assigned to Justice Yadav, and that the in-house inquiry proceeds without waiting for political convenience.

For in protecting its own house, the court protects the Republic.

(Sanjay Hegde is a senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined