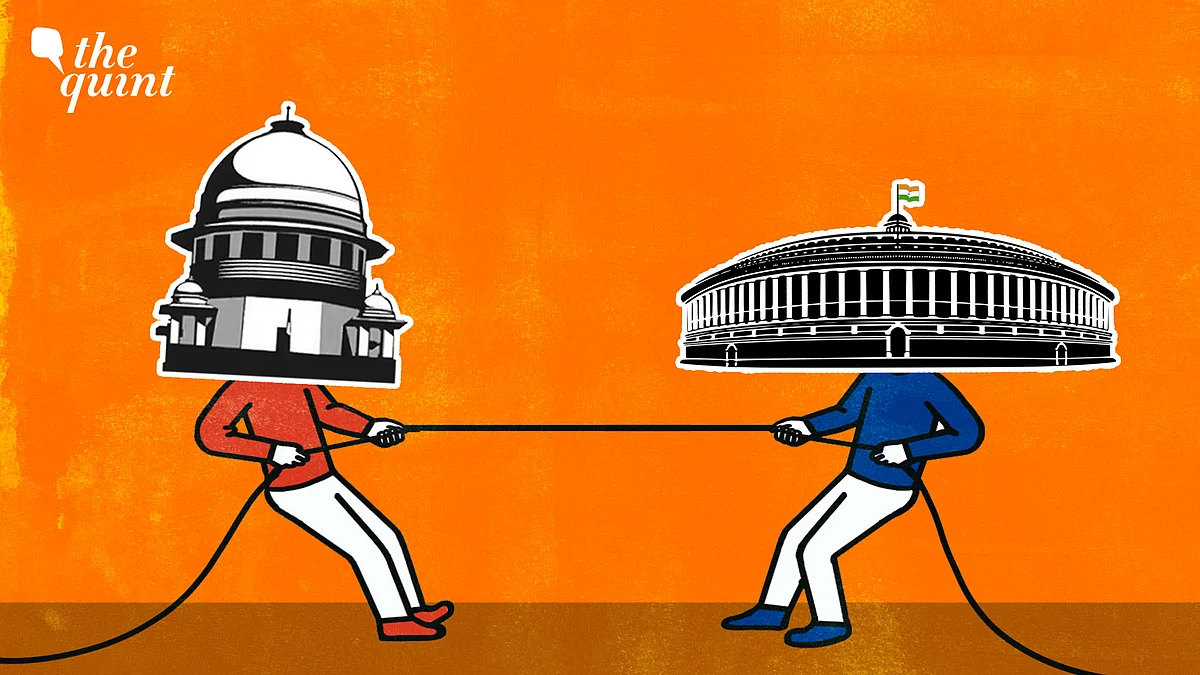

Judiciary at a Crossroads: Can NJAC and Judicial Independence Coexist?

The judiciary can't be seen as infatuated by those who view the justice system as a marketplace for orders.

advertisement

A judge of the High Court has been accused of possessing unaccounted money. The judge has strongly refuted the allegations, claiming a conspiracy to slander his hard-earned reputation. The story was broken on 21 March from sources within the judiciary.

Since then, a political campaign advocating for the revival of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) has gained momentum.

In response, the collegium, in a flurry of transfers, sent three judges of the Delhi High Court to the Calcutta and Allahabad High Court. This move provoked strong reactions from the elected Bar Councils in these courts, which issued statements questioning the credibility of the transferred judges. As a result, the collegium’s handling of judicial appointments and transfers is now facing intense scrutiny.

Myth of Executive Helplessness

The judiciary’s legitimacy was at its peak in the 1990s and 2000s, when it actively shaped India’s legal landscape by pushing for prison reforms, consumer rights, and dealt with alleged executive corruption in the UPA-II regime.

But when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014 with a majority, two critical issues emerged: (a) The power to appoint judges and (b) ideological disagreement between the judiciary and the executive over constitutional values.

Let’s not forget that even today, several recommended judges of the collegium were not appointed because the central government didn’t affirm the collegium’s recommendations. This includes notable examples such as Saurabh Kirpal and Shwetasree Majumder, whose appointments remain pending till today in the Delhi High Court.

Many times, the collegium has sought to alter its original recommendations at the request of the executive; the government clearly has a say. Let’s not forget when lawyer Gopal Subramanium was embarrassed by the government through leaked stories in national dailies, leading him to withdraw his candidature. To say that the political apparatus has no say in the appointment process would thus be incorrect.

Executive Power, Judicial Legitimacy, & Constitutional Values

Judges are now facing an ideological confrontation on constitutional issues—from free speech to religious freedom.

The prosecution has argued for an unreasonable threshold for granting bail, opposing bail on the minutest of grounds. The executive is also pushing the definition of due process through several arbitrary orders, including those of demolitions of private and religious property.

The judiciary’s response has been underwhelming, but not absent. The Vice President has suggested that judges can be held accountable only through political intervention. While much has been written about how the NJAC would cripple the autonomy of the judiciary, I am more unsettled by the way the judiciary has ceased its legitimacy.

A Judiciary at a Crossroads

The recent statements issued by the Bar Councils of the Calcutta and Allahabad High Courts (dated 21 March 2025 and 28 March 2025) highlight a loss of face for the collegium, apart from the embarrassment caused to the judges transferred. The judiciary needs to ask itself why there has been this loss of trust between the Bar and Bench to this extent.

Many within the legal fraternity worry that the judiciary is allowing the independence of the institution to be compromised by its proximity to both the executive and certain influential lawyers in Delhi.

Each allegation tears into the fabric of trust built over decades between the people of India and the judiciary. The judiciary cannot be seen as being infatuated or intrigued by those who view the justice system as a marketplace for orders or a tool for personal ambition. The judiciary is an irreplaceable facet of India’s successful global story; this should never be taken for granted.

From controversial senior designations made in 2024 in the Delhi High Court (now sub judice before the Supreme Court) to allegations of proximity of to multiple investigations into judges’ alleged connections with powerful individuals, the problems within the higher judiciary are evident.

After all, the judiciary is the only institution with the constitutional authority to check political power—this authority must be preserved at all costs.

(Abhik Chimni is an Advocate at the Delhi High Court. Riya Pahuja is a legal associate. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined