Indian Americans Must Confront Trump 2.0. History Shows How

South Asians must do their part to ensure the US doesn’t regress further. For inspiration, we can turn to our past.

advertisement

The author Suketu Mehta, when I interviewed him, noted: “All he knows about India is to say, ‘I love the beautiful Bollywood actresses!’ Any Indian who supports Trump should get his head examined, because this man is a danger to all of us. There are people in his administration who hate immigrants, particularly non-White immigrants. They want America to return to before 1965, which was when the quota on Asians was lifted.”

There’s more to it, but I should point out that the interview was done in 2019. I can only imagine what Mehta would say about Trump’s second term. Indian Americans and other South Asians who supported Trump—and worse, still support him—never cease to amaze me.

In social settings, fortunately, it’s easy to avoid political discussions, which in any case would be foolish, not to mention futile, since the “other side” and I seem to be living on different planets.

US Caving In To Authoritarianism

As the US sinks in a morass of dysfunction and authoritarianism, with anxiety spreading across the land like a bad smell, corporations are caving and revered institutions seem to be crumbling. And people are angry. There’s so much gun violence (American civilians, according to one estimate, own 500 million firearms) that foreigners must be wondering how long the nation can go on like this without making drastic changes.

It's no exaggeration to say that a huge chunk of the US population is in a state of shock. What’s happening to the country that immigrants, especially, have long idolised as the best and most desirable place in the world to call home?

Also troubling is Trump 2.0’s implicit and explicit embrace of White Christian nationalism, whose resurgence today is undeniable. Does it share at least some parallels with the embrace of upper-caste Hindu nationalism in India under the BJP? I believe it does.

History of Rampant Prejudice

A relative, who wanted to remain anonymous, was having lunch with an older Black woman, a former colleague, when the conversation turned to how things were going downhill and how the Trump administration, with its policies, had turned against immigrants and people of colour.

“Oh, that’s nothing new for us,” the former colleague said. “We’ve been through this before.”

Indeed. Not only did Blacks in the US face rampant prejudice and discrimination, but they had to fight against it pretty much on their own. Nowhere was the struggle more intense than in the Jim Crow South. When the first big wave of Indians came to America in the 1960s, after the Civil Rights Act and the Immigration and Nationality Act were passed, they gravitated to the two coasts and the Midwest. Yes, they came to the Deep South as well, but in smaller numbers.

What may be surprising is that Indian immigrants were living in the Deep South even before desegregation. Actually, it should come as a shock, because life for “coloured” folks was very different in a society that resembled South Africa under apartheid, which means “apart-hood.”

Ideas and inspiration can come from several sources, with one example being Zohran Mamdani’s highly effective grassroots campaign for Mayor of New York City. We can’t be casual about next year’s midterms, which will be a crucial test for the opposition. Something as simple as marching in a peaceful protest march should be a no-brainer.

The Indo-US rift is also deeply troubling, and Indian Americans can surely do more to foster better understanding between the two largest democracies. Our voices should be heard. Calling the offices of elected officials and writing letters doesn’t take a lot of time or effort. We should organise, facilitate, and act.

For inspiration, we can turn to our past as well.

The Past As a Guiding Light

While the Deep South in the 1960s and earlier didn’t have many South Asian immigrants, and immigrants generally didn’t participate in the civil rights battles, there were exceptions. Nico Slate, a historian at Carnegie Mellon University, mentions them in 'Colored Cosmopolitanism: 'The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India'.

For instance, at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi, two professors—Indian immigrant Savithri Chattopadhyay and Pakistani immigrant Hamid Kizilbash—supported the Black students who were involved in the protests and other desegregation efforts of the mid-1960s.

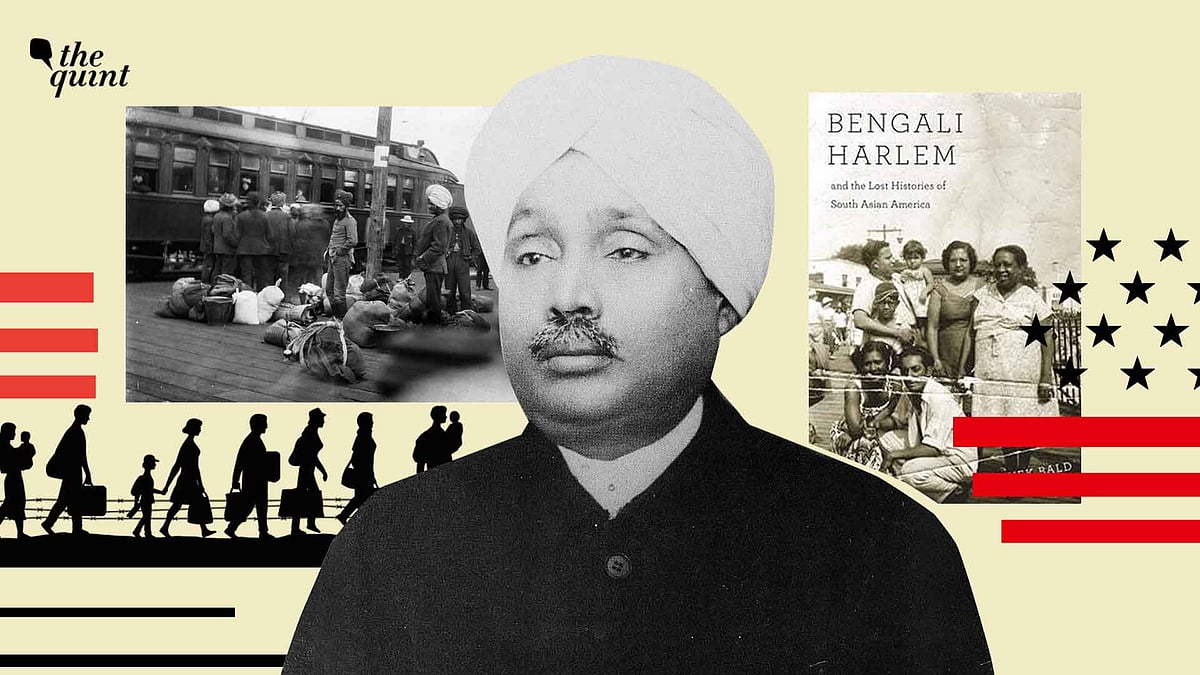

And fascinatingly, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the scholar Vivek Bald has shown, mostly Muslim tradesmen from India settled in segregated New Orleans, where many of them led vibrant lives after they married Black and Creole women. In Search of Bengali Harlem, a film made by the comedian Alaudin Ullah and Bald, tells that story with panache.

The Bengali Harlem story is not unlike the Sikh-Mexican story in California, where Indian farmers often married women who had migrated from Mexico. Anti-miscegenation laws and racial discrimination didn’t mean that non-White immigrants couldn’t lead rich family lives.

Bengali Harlem book cover.

Lala Lajpat Rai.

(Photo: Wikipedia)

Then there was a journalist named Sant (aka Saint) Nihal Singh, who was galvanised by the race riots of 1907 in Bellingham, Washington, where an angry mob of about 500 White workers attacked and drove out the Indian labourers living there. The headline in the local newspaper read: “Hindus Hounded from City.” In fact, most of them were Sikhs.

The following year, after travelling through the Deep South to get a better understanding of the race problem, SN Singh wrote an article (“The Color Line in the United States of America”) in which he pointed out how “the negro is uplifting himself despite [the] odds.”

In addition, there were noteworthy Gandhian academics who lived and worked in America. In Yellow Springs, Ohio, Manmatha Nath Chatterjee helped students establish Ahimsa Farm, which was involved in desegregation efforts. Krishnalal Shridharani, who participated in the Dandi Salt March, earned three degrees from Columbia and New York University. His 'War Without Violence' was an important text for the Freedom Riders and other activists of the civil rights movement.

Scholar Seema Sohi, who has deeply researched the legacy of early Indian immigrants, makes a good point in an article that was published last year by the South Asian American Digital Archive.

“South Asian migrants contested exclusion, racial violence, and political repression in creative, innovative, and bold ways,” she notes. That’s worth remembering today.

(Murali Kamma is a managing editor and writer based in Atlanta, Georgia. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author's. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined