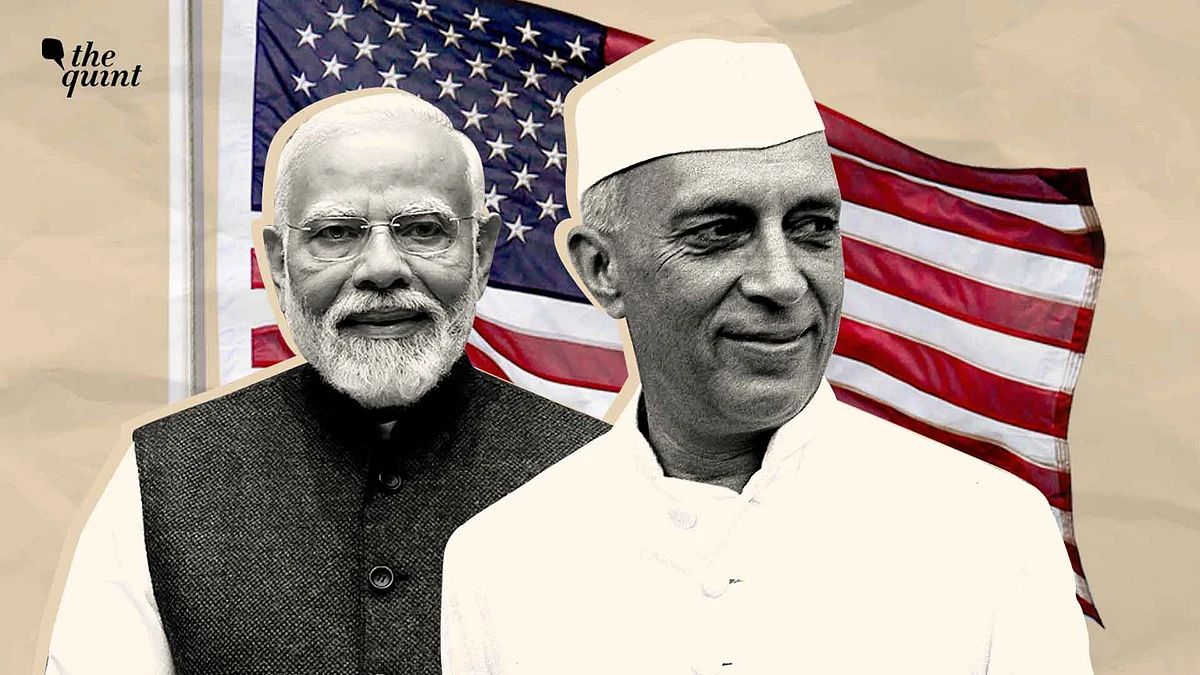

Modi to Nehru, India Has Always Dealt with Insensitive Americans

The US may not look kindly to India's attempts at running with the hare and hunting with the hound.

advertisement

As they face the US President Donald Trump’s hostility, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his foreign policy advisor would do well to reflect on their bête noire Jawaharlal Nehru’s visit to the US in October 1949.

That era and the nature of the personalities in both countries were entirely different. It is therefore easy to think that Nehru’s visit can offer no useful clues to Indian policy makers as they grope to find a way to deal with the negativity introduced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s apparently erstwhile friend Donald, in what was a bilateral relationship moving strongly forward.

That would, however, be a profound mistake because the pressures put on, and the demands made of Nehru by the Harry S Truman administration were on some of the same matters which currently divide India and the US.

Truman-Nehru: A Precursor to Trump-Modi

Despite the very warm welcome accorded to Nehru by Truman at the time, little attention was given to India’s core concerns. Yes, the language was not as blunt, indeed brutal, as is being used now by US officials.

An example of its intemperate nature can be found in the White House Counsellor for Trade and Manufacturing, Peter Navarro’s recent article in The Financial Times. Reiterating the charge that India had helped Russia finance its war on Ukraine through its purchase of discounted Russian oil, Navarro went on to state that transferring cutting edge defence technology to India was “risky” because it was now “cozying up to both Russia and China”.

Compare these words with India’s repeated emphasis that it has a ‘Comprehensive Global Strategic Partnership’ with the US. Indeed, the Indo-US Joint Statement issued after Modi’s meeting on 13 February this year at the White House began thus:

Six months later these words sound ironic.

Trump has got very very miffed at India’s refusal to recognise his oft-repeated assertion that it was his intervention that brought an end to India-Pakistan hostilities in May before it could develop a nuclear dimension.

He is also angry that India has taken a tough position in the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) talks on agriculture and dairy. To add to these, Trump has targeted India (but not China) on the issue of the purchase of Russian oil.

American Insensitivity is Not New

Prominent Indian historian Sarvepalli Gopal has, in the second volume of his biography of Nehru, covered the stormy 1949 visit. He noted that on several occasions, American behaviour bordered on the discourteous and insensitive. This included a lunch hosted for Nehru in New York with US businesspersons.

At a time when India’s GDP was US $5.86 billion, Gopal records that the "wealth and material prosperity (of the US) were occasionally flaunted as at a lunch of businessmen at New York, when Nehru was informed that US$ 20 billion was collected round the table”.

The comparison essentially reduced India to a minor player in global economics.

Over the past two decades, India-US ties have experienced the warm, comforting winds of globalisation. Trump’s icy, Arctic blast out of the blue has thus caused much consternation in Delhi.

While sudden gusts of cold winds may have been missing in 1949, the American response to Nehru was no less icy. As Gopal writes, the “official discussions with Truman and (Dean) Acheson [Secretary of State]...failed to develop any cordiality or understanding. Both sides adopted condescending attitudes. Nehru hotly defended India’s position on Kashmir and was critical of the equivocal attitude of the United States”.

The real question is whether Trump was offering to mediate in what India has considered a strictly bilateral issue since 1972, ie, the matter of Jammu and Kashmir. India has not allowed any third party to intervene on this issue.

Naturally, in 1949, the matter was under the active consideration of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and India had allowed the P5, the five permanent UNSC member nations, to purvey the issue according to their own national interests. That Nehru made a mistake in taking the matter to the UNSC on 1 January 1948 is well known. What is not so well known is that within six to seven weeks of doing so, he had realised that it had been a colossal mistake.

The Old Agriculture Debate

In 1949, India’s agriculture was in a woeful condition and in need of grain from abroad. What Gopal notes in this context is relevant today when Trump wants Modi to allow imports of US agricultural products, which India cannot allow. Understanding why requires Trump to be sensitive to the fact that 50 percent of Indians depend on agriculture, even though it contributes around 15 percent of the country’s GDP.

As of now, Trump is refusing to be sensitive. Much like Truman who had shown the same degree of insensitivity to India's needs at the time.

Nehru, however, had mentioned India’s needs of ‘food and commodities’ to him in general terms. He refused to ‘beg’, which is perhaps what Truman had hoped he would do. Consequently, as Gopal writes:

The China Conundrum

Finally, there was a great difference on China. The US did not want India to recognise the People’s Republic and “disagreed with Nehru’s assessment of events”. Now, of course India is part of the QUAD and its summit will be held this year. But Navarro’s comment that India is cozying up to China shows how Washington may interpret Chinese Foreign Minister’s Wang Yi’s current visit to India.

Rebuffed in Washington and with the onset of the Cold War, Nehru had turned to non-alignment as the core of India's foreign policy. Now, what choice does Modi have but to turn to multi-alignment—a new-fangled term, for non-alignment? In this process, Nehru had to make what can now be considered as concessions to China. After the Galwan clashes, would s re-set with China not overlook its inexplicable 2020 conduct?

In the final analysis, it appears that Modi and his main foreign policy advisor, who has no such expertise on the US today in Trump’s second term, may have no alternative but to agree with how Nehru assessed his visit. As Gopal pens it, “Nehru’s own assessment at the time was that the United States Government expected acquiescence from him on all issues, and was unwilling to assist India for anything less”.

(The writer is a former Secretary [West], Ministry of External Affairs. He can be reached @VivekKatju. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined