On Gandhi Jayanti, Rethinking the ‘Muslim Appeasement’ Myth

Some accuse Gandhi of appeasing Muslims, saying it fuelled Partition. But that claim is far from the truth.

advertisement

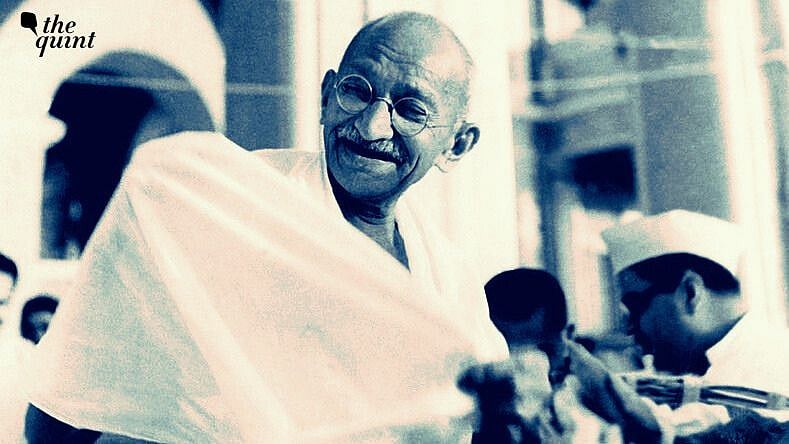

As we commemorate Mahatma Gandhi’s 156th birth anniversary, it’s worth reflecting on a criticism that is often levelled against his otherwise remarkable legacy.

Some Indians—particularly those aligned with the Hindutva ideology—accuse Gandhi of appeasing Muslims during the freedom struggle. They argue that this supposed favouritism encouraged the demand for a separate nation: Pakistan. However, this claim could not be further from the truth.

When Gandhi returned to India from South Africa in 1915, the British policy of "Divide and Rule" was already deeply entrenched. In 1905, they had partitioned Bengal along religious lines, creating a separate province—East Bengal—with a roughly 70 percent Muslim population. They also supported the formation of the All-India Muslim League to represent specifically Muslim interests.

In 1909, they went a step further by introducing separate electorates for Muslims across British India. Although the Bengal partition was annulled in 1911 due to a united Hindu-Muslim resistance, the introduction of separate electorates had already planted lasting seeds of religious division.

The Lucknow Pact

Before Gandhi took charge of the freedom movement, the British narrative of Hindu-Muslim division had already begun to take root among Indians themselves. In 1916, the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League signed the Lucknow Pact, agreeing to continue the system of separate electorates and to grant Muslims political representation greater than their population warranted.

The Pact was championed by Mohammed Ali Jinnah and Motilal Nehru. At the time, Jinnah was a strong advocate for Hindu-Muslim unity. He famously said, “My message to the Mussalmans is to join hands with your Hindu brethren. My message to Hindus is to lift your backward brother up.” He was hailed as “the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity” by none other than Gopal Krishan Gokhale, Gandhi’s political mentor.

Gandhi wrote, “To extend the Lucknow Pact doctrine or even to retain it is fraught with danger. To ignore the Mussalman grievance as if it was not felt is also to postpone swaraj. Lovers of swaraj cannot therefore rest till a solution is found which would allay Mussalman apprehensions and yet not endanger swaraj. Such a solution is not impossible.”

Gandhi set out to address Muslim concerns and foster a sense of genuine brotherhood between communities. In 1920, he led the Congress to join forces with the ongoing Muslim-led Khilafat Movement—a campaign protesting the British government's humiliating treatment of the Turkish Caliph after World War I.

The Khilafat Movement

Gandhi’s support for the Khilafat Movement is often cited as evidence of Muslim appeasement, but the facts tell a different story. The movement was backed by many Hindu nationalists, including Swami Shraddhananda, a prominent Arya Samaj leader.

It played a crucial role in mobilising large numbers of Muslims to join the Congress and the broader freedom struggle. During this period, Hindu and Muslim leaders shared platforms, addressing joint rallies and protests across the country. People from both communities boycotted British goods, resigned from government jobs, returned colonial titles, and refused to cooperate with British institutions. In major cities, joint demonstrations and hartals became common, providing visible and powerful signs of Hindu-Muslim solidarity.

Gandhi faced criticism for his muted response to the violence. While he condemned the atrocities, he primarily blamed the British government for failing to protect the Hindu minority. Determined to keep the Non-Cooperation Movement on course, he urged Indians to remain committed, stating: “The sincere noncooperator now has a heavier burden to carry.” However, when in 1922 a mob of protestors killed several policemen in UP’s Chauri Chaura, Gandhi called off the Non-Cooperation Movement.

Signs of Success: Congress Gains Muslim Support

Despite setbacks, Gandhi’s effort to bring Muslims into a united front against British rule achieved significant success.

A key example of this shift came in the early 1930s, when the British convened three Round Table Conferences to address India’s communal issues. Muslim leaders’ demand for separate electorates was firmly rejected, reflecting the waning influence of separatist voices. Gandhi was able to openly declare, “the Sikhs and the [Hindu] Mahasabhites are not prepared to accept the terms.”

Another clear sign of Gandhi’s success in sidelining the Muslim League came in the 1937 provincial elections. The Congress emerged as the largest party in 9 out of 11 provinces, securing an outright majority in 7 of them. In contrast, the Muslim League, under Jinnah’s leadership, performed poorly—even in Punjab and Bengal, provinces where Muslims were in the majority. The most striking result was that the League won only 109 out of 492 seats reserved for Muslims.

The Real Causes of Partition Lay Elsewhere

So, it wasn’t Gandhi’s so-called “appeasement” of Muslims that led to India’s Partition.

The real causes lay elsewhere — in the British strategy of deepening Hindu-Muslim divisions, Jinnah’s political manoeuvring in collaboration with the British, and Jawaharlal Nehru’s failure to include the League representatives in provincial governments, and recognise the strategic military importance of India’s northwest, a region with a Muslim majority, to British geopolitical interests.

India’s Partition was a complex event, driven by a mix of errors in judgment and calculated moves by various actors. Of all those involved, Gandhi is perhaps the least deserving of blame.

(Bhanu Dhamija is Founder and CEO of the Divya Himachal Group and author of ‘Why India Needs the Presidential System’. He can be reached @BhanuDhamija. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined