Deadlock Over Aurangzeb: Rethinking South Asian History Writings

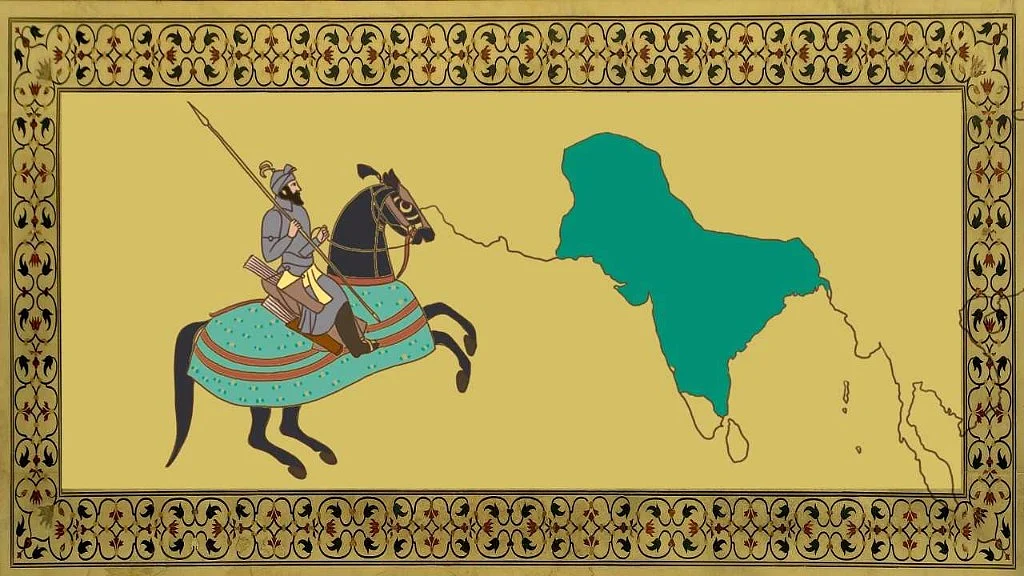

The recent controversy surrounding Aurangzeb is a vivid example of how intensely history can be contested.

advertisement

History in South Asia is not merely about defining and interpreting the past; it is a battleground where actors from the present continuously engage with and activate the past to stake their claims and assert their space. The recent controversy surrounding the 17th-century Mughal ruler Aurangzeb is a vivid example of how intensely history can be contested, both in the popular domain and among professional historians.

A section of the Hindu right-wing, including groups like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and Bajrang Dal, seek to demolish structures associated with Aurangzeb, viewing them as symbols of cruelty and violence against Hindus.

The Hindu right-wing's sentiments were further fueled after the release of the film Chhaava, where Sambhaji, the Maratha ruler, is depicted as being brutally tortured by Aurangzeb.

This sparked demands for the demolition of Aurangzeb's tomb and the burning of a sheet with the Kalma, leading to violent clashes in Nagpur City.

In response, historian Mridula Mukherji argued on television that the current regime's invocation of the past is politically motivated and will lead us nowhere. Others in civil society pointed out that if we are to count the violence of early modern and medieval India, we must also consider the long histories of oppression by Brahmins and feudal caste Hindu rulers against those at the social bottom.

Some even criticised filmmakers for misusing creative freedom to stoke hatred against Muslims.

Amidst these conflicting voices, it is easy to forget that political parties and the right-wing are not the only ones invoking the past; Indians, in general, are deeply connected to their identities shaped by caste, religion, region, and tribe. Over centuries, they have internalised myths, legends, and icons that have become integral to their common sense and essence. To appeal to these constituencies, political parties across the ideological spectrum express their allegiances to the past and pay tribute to these symbols.

Caste, Popular History and Mythicisation of the Past

Recently, conflicts such as the battle between Gujjars and Rajputs over the medieval King Mihir Raja Bhoj in Rajasthan or the violence by certain dominant Shudra castes against Dalits in Tamil Nadu while claiming a warrior past, serve as examples of how Indians are engaged in intense debates over their history. It’s important to recognise that claiming or mythicising the past is not always a horizontal competition for power between equally situated groups.

Karthikeyan Damodaran’s work on the Pallars of Tamil Nadu is one such example. While academic historians may argue that the popularisation of caste in cultural narratives can lead to the reification and essentialisation of identities and myths, they must also reflect on the histories they have provided for marginalised groups who were denied writing and may still lack the resources or institutional capacity to create formal history. Should they forever be relegated to the status of the masses, peasants, and workers?

On the other hand, the enormity of Mughal history in both popular imagination and academic discourse, the long history of Hindu-Muslim conflict, and the prominence of Hindutva in Indian politics make figures like Aurangzeb highly contentious. When such figures are projected into the public sphere, they spark debates and emotions on an unprecedented scale.

This is difficult to avoid in India, where such histories are repeatedly told in communities through stories, legends, songs, visuals, and emotional appeals. It would be futile to moralise the popular rendering of history through academic debates; instead, one can only hope that, over time, popular engagement will shift toward a more objective understanding through better curricula and spread of information.

In areas where they do not hold power, they should play a mediating role among communities to help deescalate conflicts.

Lalu Yadav’s famous speech against LK Advani during the Ram Mandir movement comes to mind when one thinks of such possibilities. At the same time, Academic historians must be evaluated based on certain normative standards, as they have access to sources and information that others may not. Their writings and speaking can be blown out of proportion and precipitate conflicts.

In this context, I will now examine some of their interpretations of Aurangzeb’s reign.

Writings on Aurangzeb and Contesting Interpretations

Over the years, numerous books have been written on Mughal history, starting with figures like Jadunath Sarkar, Irfan Habib, Satish Chandra, Athar Ali, Syed Ali Nadim Rezavi, Richard Eaton, Rajmohan Gandhi, and William Dalrymple. However, the most fiercely contested work on the subject is Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth by Audrey Truschke, a professor at Rutgers University.

Truschke argues that her goal is to recover the historical figure of Aurangzeb, separating him from the vilified version created by Hindutva in their anti-Muslim narrative. There are several sources from the 17th and early 18th centuries—such as Mughal state archives, Maasir-i-Alamgiri, European travelers and physicians like Bernier and Manucci, as well as figures like Bhim Sen—that provide insights into Aurangzeb and his reign. However, there is no consensus on the nature of his rule or its impact on the people.

The issue cannot be simply reduced to a binary of Hindutva exaggeration versus liberal objectivity or Muslim appeasement versus Indic truths, as is often suggested. While Hindutva grossly distorts numbers, liberal historians tend to explain away violence. There is much more to unpack in this debate and our understanding of this period in history.

I argue that the impasse surrounding Aurangzeb, as well as the reading of many other aspects of medieval and early modern history, lies in the tendencies through which both sides shape public discourse.

South Asian Exceptionalism and Truschke

Scholars associated with the South Asian Exceptionalism school range from nationalist historians to post-colonial theorists, who argue that the Hindu-Muslim conflict and the essentialisation of caste and religious identities are largely products of colonial policies.

Notable figures who have advanced these ideas include Bipan Chandra, Mridula Mukherji, Arjun Appadurai, Bernard Cohn, Nicolas Dirks, and Gayatri Spivak. However, when it comes to the concept of caste, this view has been challenged by scholars such as Sumit Guha, Sanal Mohan, Rupa Vishwanath, and Divya Cherian.

This approach sought to measure practices, events, and societies in India not by Western Enlightenment standards but by the norms and values of Indian society.

Although there were other significant approaches to writing histories, such as the seminal studies on feudalism, social stratification, and land holdings in medieval India by historians like DD Kosambi, RS Sharma, DN Jha, Burton Stein, and Noboru Karashima, who focused on the rise of Brahmin power through land and revenue grants, village grants, and rise of intermediary castes as landed elites, the trend of South Asian exceptionalism gained momentum during the decolonisation turn and gradually overshadowed these other historiographical approaches.

These themes came to dominate the study of pre-colonial South Asian history, leading to the marginalisation of narratives focused on oppressive socio-economic structures, modes of production, and the broader masses of Indian society, as attention shifted towards these specific themes and select groups of people.

To counter the portrayal of Aurangzeb solely as a religious fanatic and megalomaniac by Hindutva, Truschke to the other extreme, explaining away his violence either as political maneuvering or as a reflection of the norms of medieval and early modern governance.

Truschke's Arguments on Aurangzeb vs Other Sources & Scholars

Amid an intensely polarising debate, her consistent focus on uncovering the motives behind Aurangzeb's violence, proclamations, and policies, while overlooking the impact of these events on people, often gives the impression that she is trivialising them and positioning herself as a judge for Aurangzeb. For instance, she bluntly describes the execution of Sikh Guru Teg Bahadur as a man who opposed the Mughals and was thus executed because Aurangzeb had no tolerance for revolts.

In contrast, historians like Satish Chandra, who have studied Aurangzeb's religious policies, have taken a more holistic approach. Chandra has acknowledged the religious undertones of some of Aurangzeb’s actions, such as the imposition of Jizya, the discriminatory taxation of Hindus, his anti-Shia sentiments in the attack on Hyderabad, and the calls to damage certain temples, while placing these policies within the broader political and economic context of the time.

He argues:

Furthermore, Truschke argues that British colonialism was reprehensible even by Indian standards while urging that the period of Aurangzeb be evaluated according to the norms of that era.

This call for exceptionalism creates space for the emerging group of Indic scholars, who often downplay issues like feudalism, caste oppression, the subjugation of women, and the exploitation of peasants and agricultural laborers under Hindu regimes such as the Cholas, Nayakas, and Rajputs. It is insightful to examine how contemporaries perceived the circumstances of the time.

Bhim Sen, a Kayastha man from present-day Uttar Pradesh who served under Aurangzeb, wrote the following in his memoir Tarikh-i-Dilkasha: 'There is the oppression of the faujdars, Deshmukh, and Zamindars, who take money from the peasants on every conceivable plea; the Zamindars pay not a penny out of their purses, but take it from the ryots and make payment to the emperor’s agents. What shall I write of the violence and oppression of the amins appointed to collect the jizya that has been newly imposed, as they are beyond description?’

These peasants, both Hindus and Muslims, are often overlooked in the narrative of South Asian exceptionalism, which tends to focus on countering the accusations of religious intolerance leveled by Hindutva by emphasising certain religious grants given by Mughal rulers and cultural exchanges between Hindu and Muslim elites in the courts.

It is well-documented that most conflicts between the Mughals and regional forces, as well as the revolts, were primarily political, with alliances often crossing religious lines and sections of Brahmins receiving land grants.

However, this argument is primarily used by scholars like Ram Puniyani and Ruchika Sharma to downplay other contradictions, such as occasional religious discrimination, the Jagirdari crisis, the corruption of the nobility, and the strain on the imperial treasury caused by the Deccan wars.

Indic Scholars and the Lie of Hindu Protectionism

The inconsistencies in framing the debate around religious tolerance—while simultaneously avoiding it—along with the silencing of mass subjects and the neglect of exploitation by both Hindu and Muslim elites, allow Hindutva-leaning Indic scholars to narrow their opposition to a purely religious framework (such as Anand Ranganathan and Sai Deepak).

In 17th-century Marwar, Rajasthan, Dalits were not only forced to work as agricultural labourers but also subjected to Begar (unpaid forced labor) imposed by the Rajputs. These practices were not innovations of the Mughals but long-established features of Hindu society. The Rajputs and Marathas were not fighting to protect the oppressed but rather to secure their territories and revenues, with religious overtones emerging at times. Simultaneously, many held land grants and high positions under the Mughals.

Moreover, the establishment of Mughal offices and courts brought substantial benefits to Brahmins and Kayasthas, and their migration is framed by right-wing Hindu historians like Meenakshi Jain as an act of protecting Dharma.

Historian Rosalind O’Hanlon writes the following about the Brahmins of Western India:

Gail Omvedt, describing the power of Brahmins before the rise of Muslim rulers, writes: “At the local level, they gained new control over land and the people on it, as the proliferating land grants after the 7th and 8th centuries attest; and at the top, they were temple priests, administrators, and legitimators of the often barbarian kings.”

It is important to highlight that the so-called ‘barbarian kings’ mentioned here actually came from landed Hindu castes. Therefore, the Hindu elites, particularly the Brahmins, were not protecting the masses, many of whom they now refer to as Hindus. Instead, they sought power and influence by subjugating Dalits and other marginalised caste groups.

Pathways to Better History Writing

A certain section of Hindu upper-caste liberals in Delhi, quite influential in the civil society, exhibit a palpable nostalgia for a past aristocracy, which allows them to romanticise South Asian history. Some even romanticise the Rajput symbolism and architecture as a vibrant Indian past. On the other hand, Hindutva groups use nostalgia to invoke a tragic yet heroic past, using it to fuel animosity toward Muslims.

The Hindu right’s visible voices are divided over the desire for a pure Brahminical Caste order that they believe has been compromised due to modernity and constitution and the need to include Dalits and OBCs due to political exigencies by letting go of some of the extreme caste practices.

This is an ongoing debate between a section of prominent Brahmin clergy and RSS, but their ultimate goal is to incorporate the former groups in an imagined glorious Hindu past disrupted by Mughals.

This will help break the current deadlock in historical understanding that has deeply influenced public perception. However, introducing such perspectives into formal education will be no easy feat for governments, and it will be a risky endeavor for civil society that takes on this responsibility.

While many fundamentalist organisations are likely to vehemently oppose these efforts, embracing a multifaceted view of history, where different groups can find their place, is the only path forward.

Their approaches prevent history from being oversimplified into binary terms. As we move ahead, we should strive to accept the complexity and messiness of our past as part of our history rather than dwelling on it.

(The author hails from south Odisha and recently completed MSc in Modern South Asian Studies from the University of Oxford. He is a young researcher and anti-caste activist and his research interests are Dalit Christians, cosmopolitan elites, student politics, and society and culture in Odisha. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined