Denied Admission by BHU, Dalit Scholar's 20-Day Protest Forces Varsity to Bend

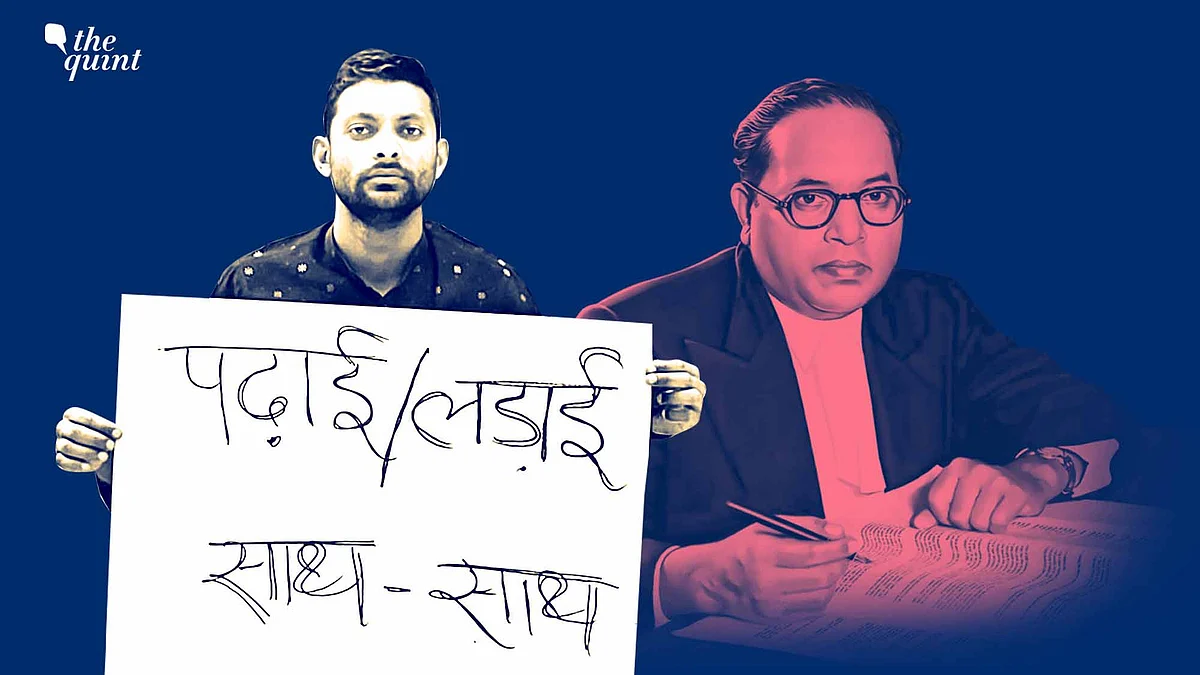

PhD student Shivam Sonkar led a small but significant revolution against the 'system'. Read his story.

advertisement

Last month, when Shivam Sonkar was denied admission for a PhD course in the Banaras Hindu University (BHU) on technical grounds, he felt distraught. He could not muster the courage to return home to his parents in Unnao and admit that he had failed to qualify again—the first time was in 2022. He felt wronged.

After exhausting all options of redressal and running from pillar to post, Sonkar, who belongs to a Dalit community, decided to sit on a dharna outside the BHU vice-chancellor’s office.

After exhausting all options of redressal and running from pillar to post, Sonkar, who belongs to a Dalit community, decided to sit on a dharna outside the BHU vice-chancellor’s office.

(Photo Courtesy: Omar Rashid)

The serious nature of his allegations towards a prestigious central university created a political stir. And within days of his sit-in, the matter snowballed into a political spectacle.

Opposition parties and leaders scurried to the sprawling BHU campus in Varanasi to take up Sonkar’s cause and target the Narendra Modi-led Central government for allegedly discriminating against Dalit scholars.

Scholar and Rebel

The image of 26-year-old Sonkar, sleeping on the road, with books, posters, banners and images of BR Ambedkar, BHU co-founder Madan Mohan Malviya, and the Hindu deity Ram scattered near him, resonated across political lines on social media. Sonkar said while talking to The Quint:

The Dalit scholar can afford to look back at the dharna with a sense of pride, and more importantly relief. On 9 April, after protesting on the street for almost three weeks, Sonkar was granted admission. The University Grants Commission (UGC) approved BHU’s request for a second round of PhD admissions and allowed the varsity to transfer the vacant seats of the RET-free (Research Entrance Test-exempted) category to the RET (Research Entrance Test) category and admit students from the applied waiting list.

“When I sat for the dharna, I said to myself ‘let’s see what happens’. People even called me crazy. They thought I would protest for a few days and resign to my fate. But ultimately the truth won," Shivam Sonkar told The Quint.

(Photo Courtesy: Omar Rashid)

BHU said it took the step to change this system in the “interest of students to fill the seats left vacant” after the first phase of admission. “The university's endeavour is to ensure that seats do not remain vacant, deserving candidates get the opportunity to do research and to promote teaching and learning in the university,” the university said on 5 April.

Sonkar felt vindicated.

That Dalits are grossly underrepresented in India’s research and higher studies is a reality that modern India still grapples with. This is often layered in institutional bias, seclusion, and omissions.

Sonkar grew up in Unnao, a district neighbouring Uttar Pradesh’s capital Lucknow, in a lower middle-class household.

(Photo Courtesy: Omar Rashid)

He grew up in Unnao, a district neighbouring Uttar Pradesh’s capital Lucknow, in a lower middle-class household. His mother ran the household while his father worked at construction sites, specialising in shuttering.

Sonkar bore the heavy weight of his family’s expectations that one day he would build himself a career in academics. After completing his schooling in different schools in Unnao, he went to BHU for his graduation, after which he applied for a PhD in the Malviya Centre for Peace Research under the faculty of social sciences. His research proposal centered around the concept of social justice of BR Ambedkar.

Empty Seats Yet Admissions Denied

Admissions for PhD in BHU are done through two modes—the RET and the RET-exempted.

Under RET-E, students who have already cleared national-level tests such as NET and JRF are given admission without an in-house test. Sonkar had applied through the RET mode. Seven seats were allotted for PhD in the Malviya Centre for Peace Research for 2024-25.

Out of the seven, three were reserved for RET mode while four were for RET-exempted. Only four out of the seven seats were filled. Three seats were left vacant in the RET-E category in his department.

Sonkar secured a second rank in the general category in the RET mode. But he did not qualify as the university only advertised two seats in the main subject under RET, one for general and another reserved for OBCs, and one seat for an allied subject (also general). Sonkar held the second rank in the general category, which means he did not qualify for the main discipline.

“This is like the academic murder of a Dalit student like me,” he said in a letter addressed to President Droupadi Murmu after his rejection. He accused the professors and officials of BHU of harbouring an “anti-Dalit mentality.”

He also sent several petitions to higher authorities requesting them to legally transfer the vacant seats of RET-E to RET, citing the principle of natural justice, equality before law and protection from discrimination.

Gaining from Competitive Caste Politics

Sonkar received sympathy and support from various Opposition leaders, who visited his dharna site. Ragini Sonker, a Dalit MLA from the Samajwadi Party, joined Sonkar’s dharna for a day under the slogan of ‘Bhim Shiksha Adhikar Manch.’ She also met Union Minister for Education Dharmendra Pradhan and UGC chairperson M Jagadeesh Kumar in Delhi to seek justice for Sonkar.

The MLA sought President Murmu’s intervention and, in a letter to her, said that Sonkar’s was a “serious case of hampering the educational opportunities of Dalit students, which is contrary to the principles of social justice and equality of the Constitution.”

Chandra Shekhar Aazad, MP from Bijnor, raised the matter in Parliament and wrote a letter to the BHU VC highlighting the “unjust treatment being meted out” to Sonkar. Denying Sonkar admission raised “serious questions on the transparency of the admission process and the principles of social justice,” said Aazad.

Within weeks, Sonkar’s quest for admission in a central university located in PM Modi’s constituency transformed into a question of larger political accountability towards the marginalised castes.

(Photo Courtesy: Omar Rashid)

And within weeks, Sonkar’s quest for admission in a central university located in PM Modi’s constituency transformed into a question of larger political accountability towards the marginalised castes

Sonkar told The Quint he was not fighting for himself alone: “This was an issue faced by everyone. It’s just that I came to the front. I did not bend. I was not afraid".

BHU Forced to Change Stance

BHU, initially dismissive of his claims, eventually softened its stance and changed its rules, allowing for his admission. On 26 March, the varsity said that it had received some complaints from students of some departments individually or collectively regarding irregularities in the PhD admission and constituted a committee to review the eligibility criteria for admission to the Centre for Inclusion Studies.

The university said that three seats advertised for the main subject in the RET-E category were vacant due to non-availability of candidates. It also underlined that according to the information bulletin published by BHU for PhD admissions 2024-25, in case a department received fewer applications than the advertised seats, the change of seats to another category was possible only before the commencement of the counselling process. In other words, the transfer of seats from RET-E to RET could not be done once the process of counselling started.

The varsity said it “vehemently deplores these attempts to spread concocted information aimed at tarnishing the image and reputation,” and stressed that no eligible candidate had been deprived of admission.

“It is a common principle that admissions are offered on the basis of merit, and those placed on the top are given preference in seat allotment. Those not figuring in the merit in a particular category have no claim for admission irrespective of their category, marks obtained, or other factors,” the varsity asserted.

BHU also tried to counter the allegations of caste-based discrimination, saying that all interview committees for PhD had a member representative from the SC, ST, and OBC categories and that all admissions were conducted through neutrality and transparency. Out of the total 791 PhD admissions done till 29 March, 429 were in the unreserved category, 198 were OBC, 74 SC, 27 ST and 63 from the Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) category. “The reservation provisions are in line with Government of India and Banaras Hindu University rules and have been followed in letter and spirit to carry out the admission process,” the BHU.

The admission process opened again on 8 April. A day later, Sonkar finally got his admission approved. “On 9 April, around 1:20 pm, I got admitted,” said Sonkar, seeming content with his achievement.

(Photo Courtesy: Omar Rashid)

This was likely to “affect the research ecosystem” of the university, BHU said, adding that it had requested the UGC to explore the possibility of introducing a second admission cycle to fill the remaining vacant seats on the basis of available waitlisted candidates. The step was taken to address the concerns raised by different interest groups through their representations regarding the conversion of RET-exempted mode vacant seats to RET mode.

A day later, BHU announced that the UGC had accepted its request for a second round of admissions. Vacant seats of RET-free category would be transferred to the RET category. “The university's endeavour is to ensure that seats do not remain vacant, deserving candidates get the opportunity to do research and to promote teaching and learning in the university,” BHU said.

The admission process opened again on 8 April. A day later, Sonkar finally got his admission approved. “On 9 April, around 1:20 pm, I got admitted,” said Sonkar, seeming content with his achievement.

“This was a fight for social justice,” said Sonkar. For him, his admission was a victory for Dalits, and in particular his Khatik community, in their fight for space in India’s academia. “If one goes through the list of those who applied for PhD, you can count those from my community on your fingertips,” he said.

(Omar Rashid is an independent journalist who writes on politics and life in the Hindi hinterland.)