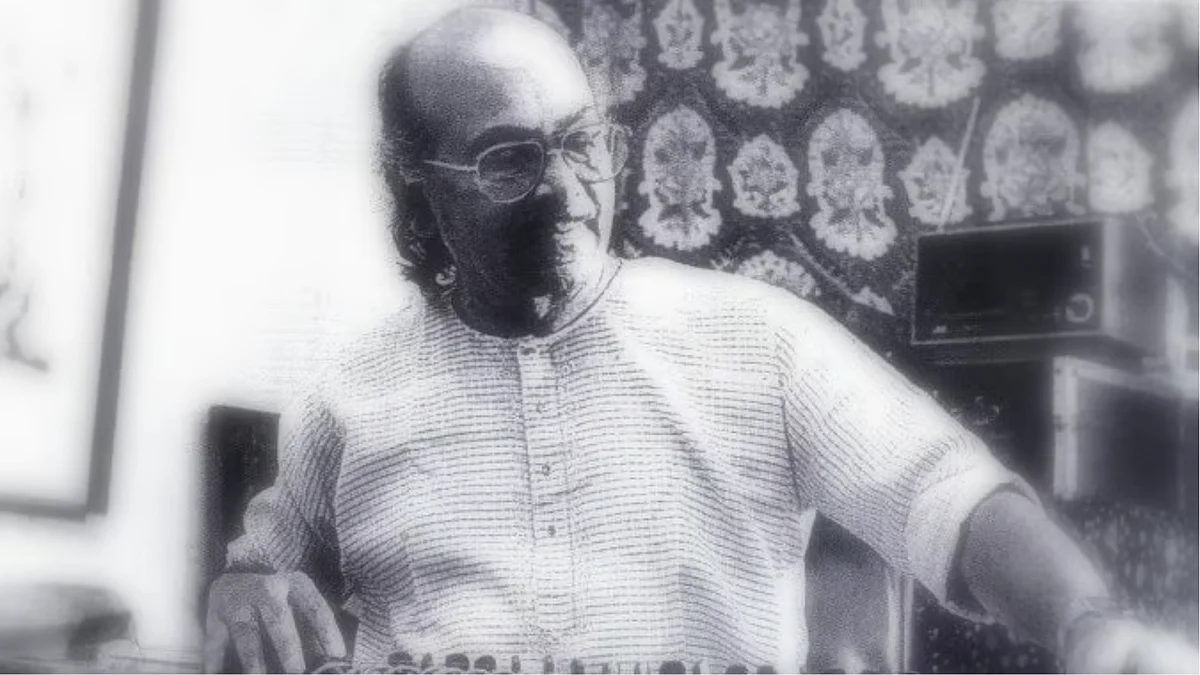

Centenary Tribute: Salil Chowdhury and His Holistic Approach to Music

Salil da made his music directorial debut with Do Bigha Zamin, a film deeply rooted in Bengali identity.

advertisement

Do you know that the year of Salil Chowdhury’s birth remains an eternal question? While some who knew him say he was born on 19 November 1923, others insist that the year was 1925. Trapped in this confusion, it would be safe to state that he perhaps stepped into his 100th year on 19 November this year.

The relationship between the visual and auditory components in cinema is both active and dynamic, affording a multiplicity of possible relations that can evolve, sometimes dramatically as the narrative unfolds, sometimes naturally, as a natural extension of the actions taking place, and sometimes to heighten the given mood of the situation or lighten the mood depending on the demands of the script and the approach, perspective, and treatment of and by the director.

Taken holistically, considering the aforementioned paradigms, film music is an inclusive concept, especially with reference to Indian cinema which defines, elaborates, and explores the ability of a filmmaker to explore and use music and songs in the most creative way to add to the aesthetics of the film and the unfolding of its narrative.

Born in Chingripota in the 24 Parganas district of West Bengal, Salil da spent almost his entire childhood in the tea gardens of Assam where his father, passionately in love with music himself, was a doctor employed in a British tea plantation company.

On the one hand, as a small boy of around four or five, he was greatly influenced by the songs of the tea garden workers, the peasants and Assamese folk songs. On the other hand, he imbibed in himself a great love for Western classical music through his father’s enviable collection of gramophone records of the compositions of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and Chopin.

Every day, his backdrop was filled with the mystique sounds of nature – the sounds of the forests, the chirping of the birds, the melody of the flute and the folk songs of the region. As a logical extension, he played the flute beautifully.

During his revolutionary phase in the freedom struggle, he always carried his flute with him and would begin to play it spontaneously. Apart from the flute, he played the esraj, the violin and the piano. He had almost a complete understanding of several other instruments, often seen in his musical creation over time.

He became an excellent self-taught flute player and his favourite composer was Mozart. His compositions often used folk melodies and melodies based on Indian classical ragas but the orchestration was very much western in its construction. He developed a unique style one could identify with easily and get to love at the same time. His daughter Antara Chowdhury often jokingly says that her father would sometimes say that he “was Mozart reborn.”

Salil da made his music directorial debut with Do Bigha Zamin, a film deeply rooted in Bengali identity, especially Bengali music. He later widened the borders of his creations and music by bringing Western music and fusion into his compositions but that did not take away his connect with Bengali folk music. The Mausam Beeta Jaaye number in Do Bigha Zamin had strong traces of the Soviet Red March song with Salil da creating a distinctly Indian alaap for the song so that it sustains the Indian identity of the film’s story and characters.

Readers may recall that Salil da took the Malayalam film music world by storm when he first composed the music for Chemmeen which won the National Award for Best Film. The CD was later brought out by Saregama HMV. After Chemmeen, he scored music for 23 films in Malayalam. Some films never saw the light of day in the theatres and some were big box-office flops. But all are referred to just for the songs.

“I felt very sad. I had scored the music for G Aravindan’s last film, Vastuhara (1991), my first for Aravindan’s film, but the director had passed away and the film died its own silent death.”

Raj Kapoor once described him as a genius who could play everything from tabla to sarod and piano to piccolo. Salil da showed Indian popular music the way to use quaint Western instruments. He used instruments as varied as the oboe, the French horn, the mandolin and the saxophone.

He was accused of Westernising Bengali music. His reply was that the harmonium, the common idiom of Indian music, was itself a Western instrument. "Music has to at all times, dissolve and evolve, ever renewing it into new forms to suit the tastes of the time. Otherwise, it will become fossilised. But in my quest for moving forth, I should not forget my tradition."

(Shoma A Chatterji is an Indian film scholar, author and freelance journalist. The views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)