Ai Weiwei’s Debut India Solo Show Is Bold, but Noticeably Careful

While visually striking, the Chinese artist’s works feel detached from the turbulence of contemporary India.

advertisement

Chinese contemporary artist Ai Weiwei’s debut solo show in India is undoubtedly brilliant. It is no mean feat to showcase and celebrate an outspoken artist amidst an atmosphere of cancel culture, boycotts, and shutdowns that are governed by which side of today’s political ideology you stand at.

A collection of his dozen pieces spanning across decades live up to his reputation of being one of the strongest art activist and political commentator on human rights abuse that the world of arts has seldom seen in the recent past.

But here is the big BUT.

Is he unaware of ground reality? One doubts it. Is he being careful and cautious for now? Certainly, yes.

(Photo: Sahar Zaman)

Art Without Urgency

This was reinforced when I asked him a question about how to encourage artists and performers in India to be unafraid of the truth and find courage to speak out. Pat came his uncharacteristic response.

He fails to acknowledge that not speaking out doesn’t always reflect a happy state of mind. It comes with the fear of being silenced too, in a constantly looming threat of tax raids and police FIRs.

Ai Weiwei has often tried to explain that an art work should be considered lifeless if it is unable to make people think or feel its dissent. But this is precisely what three of his latest pieces of work especially made for his debut solo show in India ar—lifeless.

They lack his signature outrage which he has mastered in juxtaposing with artistic aesthetics. Made with 100s of pieces of Lego toy-blocks, the three artworks for his India show are the reproduction of paintings by Indian modern masters—SH Raza, Gaitonde, and a classic pichwai (traditional cloth art). They are a beautiful tribute to the legacy of Indian art but lifeless replicas which carry zero reflection of our times today undergoing an unprecedented fraying of India’s social fabric.

I say this because his other Lego works from the past, which are also currently on display at New Delhi’s Nature Morte Gallery, are more in line with his international reputation. His Lego work featuring the most famous Japanese work, ‘The Great Wave off Kanagawa’, has an addition of the boat people riding the wave to depict the modern refugees and migrants—primarily from Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia—who risk dangerous, unauthorised sea crossings to escape conflict, persecution, or extreme poverty.

Activism in Form and Fragment

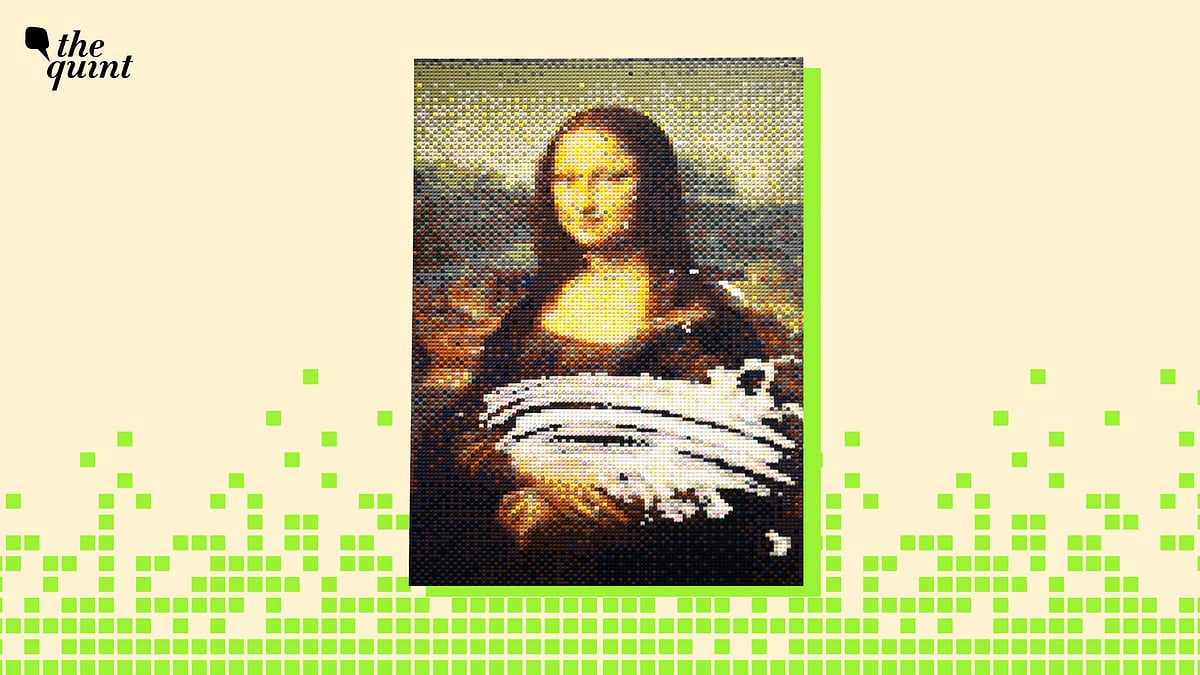

Similarly, for his Mona Lisa work in Lego, he has used white coloured Lego blocks on her hands to depict the cake which had once been thrown at the original painting in The Louvre by a climate activist.

(Photo: Sahar Zaman)

His art is like a master class on how to keep alive a rigorous dialogue that an artist should have with his/her viewer about life, lived experiences, and the right to human rights.

A tall pillar of a set of six large Chinese vases piled on top of the other is in the colours of creamy white ceramic with blue motifs. At first glance, it looks like a traditional work but up close you notice that the motifs are on the lives of war refugees. The vases show bomb attacks, destruction of homes, migration through boats, living in tents, etc.

(Photo: Sahar Zaman)

Personal History as Political Protest

Set of four military body stretchers from World War 2 are hung on the wall with multiple buttons stitched onto each stretcher to spell out the abuse, ‘FUCK’. It’s his take on how frequent conflicts across different parts of the world not just messes up your life but similar to the buttons from a factory, daily war also seems to be mass produced for commercial gains by certain countries.

The largest work in the show is, in fact, the 15-meter-long Lego recreation of Claude Monet’s Water Lillies. Ai Weiwei introduces a dark, pixelated, black-and-white portal on the right side of this triptych. This represents the door to the underground, desert dugout in Xinjiang, China, where he and his father, poet Ai Qing, were exiled in the 1960s. Weiwei experienced a second exile in his adult life.

(Photo: Sahar Zaman)

Homecoming Without Confrontation

For a brave and dissident artist who was once detained by Chinese authorities for 81 days in prison in 2011, he has recently made peace with what he defines is China’s upward phase in humaneness and personal freedom. Spending most of the last decade in exile, he finally had the chance to return home in 2025 and meet his nonagenarian mother.

Ai Weiwei himself is 68 years—and one hopes that the world’s favourite activist will keep finding the strength to use his voice on issues of human rights, freedom of speech, and government accountability.

(Sahar Zaman is an award-wining author, multimedia journalist, cultural curator and an advocate of the Orange Economy. She has Founded Asia’s first web-channel dedicated to the Arts, called Hunar TV. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)