'The Umesh Chronicles’: Amitabh Bachchan Elevates a Tender but Uneven Film

Amitabh Bachchan starrer ‘The Umesh Chronicles’ is heartfelt but uneven in its storytelling.

advertisement

Pooja Kaul’s debut feature, The Umesh Chronicles, is a heartfelt, well-meaning coming-of-age drama. Produced by Rising Sun Films and Kino Works, and executive produced by Shoojit Sircar, the film has yet to find distribution in India.

I caught it at the British Film Institute in London, where it played to a packed house.

The Umesh Chronicles is an undeniably rewarding watch for anyone willing to embrace its slow, observational rhythm as it pieces together fractured but beautiful childhood moments.

A Quiet and Meditative Portrait of Growing Up

The Umesh Chronicles follows Radha (Aiza Khan), an adolescent girl in 1980s North India. She loves getting lost in the world of movies and books; she’s fairly obedient but has a mind of her own, and has a warm relationship with her parents and grandparents, who live in an old but sprawling house in the countryside in North India.

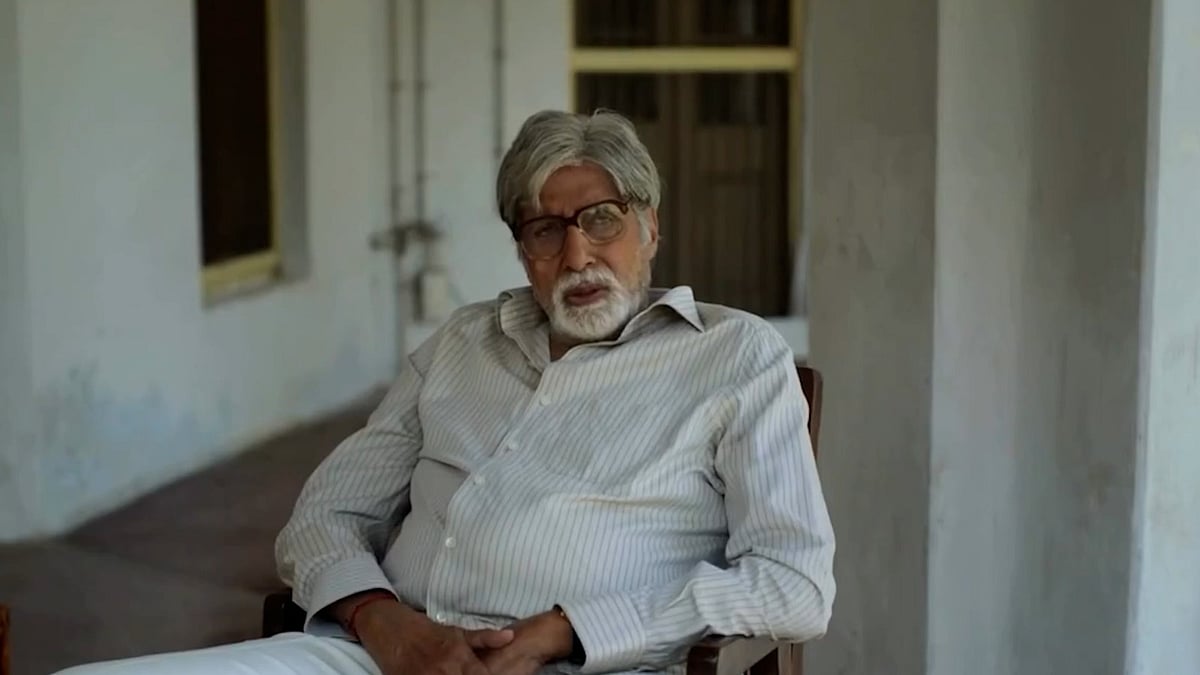

When her father (Vivek Gomber), an army man, is posted to Uri, Radha moves in with her grandparents (Amitabh Bachchan and Leela Samson) for stability and a good high school education. There, she meets Sundar (Bobby Pal), a young boy who ran away from his village and now lives and works at her grandparents’ house.

What unfolds is a quiet, meditative portrait of Radha navigating a new school, new classmates, and a growing curiosity towards Sundar. The Umesh Chronicles then shifts to her twenties in Mumbai, tracing a longer arc of self-discovery.

Aiza Khan in a still from The Umesh Chronicles

(Photo Courtesy: YouTube)

Sublime Cinematography and Brilliant Performances

The film avoids overt conflict or melodrama, instead leaning into nostalgia. Jakob Ihre’s sublime cinematography captures the characters in steady shots and soft light that elevate the beauty of the mundane—long hours of reading, meals at the dining table, and letting time pass freely.

The Umesh Chronicles is largely aided by Aiza Khan’s excellent debut, refreshingly free of any theatrics and pretense. Pal is equally compelling as the young Sundar, playing him with unaffected ease as he goes about his domestic duties in the house.

Zayn Marie-Khan in a still from The Umesh Chronicles

(Photo Courtesy: YouTube)

A Nuanced Depiction of Indian Middle-Class Life

The Umesh Chronicles is once perceptive and lighthearted, capturing Indian middle-class life with sensitivity and nuance.

For instance, Kaul repeatedly shows us how the film’s sweet familial moments are enabled by the invisibilised labour of oppressed-caste people—laying and clearing the table, cooking, cleaning, fixing, and carrying.

These undercurrents surface most powerfully in a late funeral sequence, when Sundar (now Babil Khan) returns—after abruptly leaving the household years earlier—to pay his respects. At the pyre, everyone stands around the fire dressed in white, while Sundar and the domestic worker stand apart, both in shades of red starkly marking their exclusion.

Radha’s grandfather hugs Sundar, and looks at him with concern, longing, and care. The scene captures the paradox of intimacy and insurmountable social distance—without a single dialogue spelling it out.

Where the Film Stumbles

Such restraint, however, falters when the film attempts to tie up its themes with a facile resolution. In Mumbai, Radha (now Zayn Marie-Khan) searches for Sundar in a contrived montage, and their reunion reframes the film as a cross-class love story that doesn’t land.

Not only is this ending unearned, but it also dilutes the film’s earlier subtlety in exploring the complexities of their dynamic.

Even the title, The Umesh Chronicles, exposes another blind spot. Umesh is Radha’s dhobi in Mumbai, glimpsed only in a throwaway scene. In a voiceover, she later explains her desire to get to know him better and write his story—which she would title “The Umesh Chronicles.”

Abandoning its Original Premise

In the process, the film reinforces the privileged gaze it seeks to critique. It reduces Sundar to a projection of Radha’s yearning to understand the world and her place in it, a vessel for her coming-of-age journey.

We never learn more about his life: where he came from, his challenges he faced, why he left, or what became of him in Mumbai.

Ultimately, The Umesh Chronicles feels overlong, with the uneven pacing of its third act proving especially jarring. It could have been a thoughtful examination of girlhood and growing up, but the writing lacks the cohesion, coherence, and clarity of gems like Udaan (2010) or Girls Will Be Girls (2024).

(Kaashif is a writer and film critic from Mumbai, currently based in London. He is the Assistant Culture Editor of The Polis Project.)