The revolution will not be tweeted, said Malcom Gladwell. The so-called disgust for Indian media in Nepal that triggered a hashtag for about 24 odd hours was certainly not tweeted by men and women I met in the villages close to the epicentre, even those I interrupted while they were pulling out a large rice drum from the collapsed rubble of their house in Kathmandu. Or those who had trekked down for almost half a day when they realised a small medical camp had come up. I managed to evade television and print for several days while in Nepal.

On my return one of the first things I’d say is that a strong dose of introspection by the media is needed.

When a disaster happens it seems to everyone that the low hanging fruit is to show the destruction and cycle of death. It’s not an easy task when villages turn to rubble, roads are wiped out and the bars of your mobile phone vanish. The media then takes all the help it can to witness first hand the situation and file their reports. I have taken help of friends, locals, friends of friends, government agencies-essentially anyone I know and their father to get to a spot.

I am told by Social Media that the coverage in Nepal turned out to be a public relations exercise for the Prime Minister and his government. On my return I saw some evidence of that. For instance, a graphic sting of a channel where instead of the visuals of Nepal’s overwhelming destruction, a picture of our Prime Minister, all-grim, was in focus, the text seemed to suggest his benevolent nature. Frankly, I found it nauseating.

But the truth also is that India led the rescue effort and with great competence. It wasn’t ‘the’ story but it was ‘a’ story in a country where 34 nations came down to help. In many cases, apart from dumping relief material on the tarmac and taking back their stranded nationals, they did very little. Some worked in small, incremental ways. There were others who set up small hospitals and large posters saying they stood by Nepal, took pictures and flooded their websites. There were many other countries whose PR machinery set a tent up even before the first stone was picked. So let’s face it: some grandiosity was to be expected but if it ended up making the tragedy a side- show, it isn’t journalism.

Contrary to our experiences in this country of ‘politics in the face of tragedy’, Nepal had an absolute absence of politics of any kind, both divisive or the bringing-together kind. When political leaders across party lines come together (even if it is for political capital), it gives a direction or at least a semblance of direction for relief and rescue efforts. Nepal was functioning in a vacuum of sorts. Its leaders caught in a never-ending saga of political transformation were conspicuous in their absence in Nepal’s grave time of need.

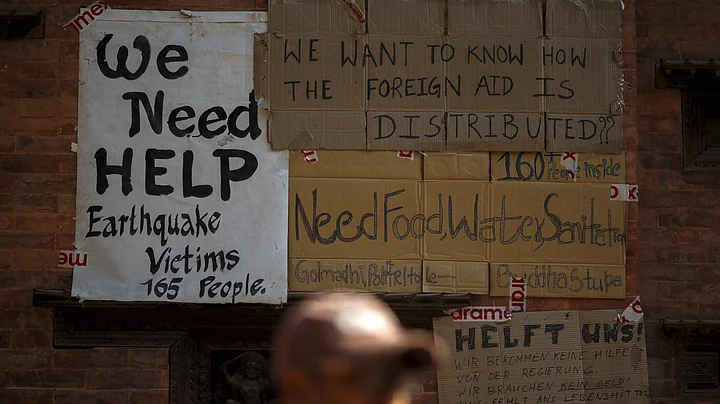

The country had no dearth of relief material. Its problem remained co-ordination. Even with many of India’s aircraft coming down, relief material distribution remained patchy. In Pokhara where India set up a base to ensure timely sorties for the nearby affected areas, on two days operations did not begin till 10 AM despite clear skies.

The airport officials opened the gates of the airport premises at 8 AM. India’s technical staff that had accompanied their machines had kept the choppers ready since about 6 AM. Some had slept close to the machines. On other occasions I saw India’s Task Force Commanders and the helicopter pilots land up in the wee hours of the morning at the Nepal’s Aviation Centre Base that became a hub of sorts. By contrast officials from Nepal walked in post 9:30 AM on many days. At other times I was privy to conversations of our pilots landing on small strips of land with co-ordinates worse than what a tourist map would have. They were accompanied by local officers who were at times confused by the destruction they saw and how natural landmarks had vanished.

Maybe it’s unfair to set down these utterances in print or in flesh in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, which is so big and hit the administrative machinery of Nepal as well. Disasters are messy and it is our job to report on this messiness. Rescue operations don’t always fit into some neat brackets that make everyone feel comfortable. Our duty in a disaster situation is to report on the suffering we witness, its many ramifications, the people who are bringing succor and those who haven’t received a morsel. The linkage from a woman who hasn’t had food for two days to the indictment of the State isn’t always obvious but once it does we need to report it.

If a few channels made this a story about the PM, there are plenty others who kept the focus on the tragedy, the magnitude, people, and rescue needed and provided. Nowhere during my reportage did I feel even an inkling of what the twitter trend seems to be suggest.

There are many things, that networks don’t do well, that journalists (or maybe Indian journalists) forget when they find themselves in a story, manners for one, sensitivity the second. The once evergreen ‘aapko kaisa lag raha hai’ question has thankfully been consigned to the dumps. We may be used to forcing our way into places and situations in our country. A foreign land reeling under a disaster and with different social moorings may not kindly take to it. But I also saw many instances of journalists trying to do their job and being shut out. They continued to persist.

The broadcast of a tragedy is what sometimes makes it a lasting tragedy. There have been many sensitively written pieces on the Internet addressed to the Indian media about giving water and food packets to those struck by the quake. We must and we should. Most journalists traverse disaster and conflict situations with a knapsack. Mine had a bottle of water, a half-eaten packet of biscuits, a change of clothes and my medicine for migraine, along with a sleeping bag. If my biscuit could have saved someone’s life I would have without any hesitation handed it over. But if I thought it would spark a crisis putting those around or my team at risk I would have to make the tough choice of not taking it out. You see the last thing a journalist in the disaster zone should be is a liability and take the focus away from a rescue effort or become the news herself.

In my job as a television journalist, I spend a lot of time boiling down experience; the medium sometimes doesn’t lend itself to nuance nor to analysis, except of the simplest kind. It generates verbiage like social media second after second when people speak and comment, thus making the first ripples of a trend. Frankly since the media at large does so much of hashtag journalism, it was only a matter of time that a hashtag came to hit us on our face.

But we are well aware of the mathematics and science of generating a twitter trend, aren’t we? The outsized enthusiasm of social media has even made me trend on numerous occasions with my small count of followers. A hashtag maybe many things but it certainly wasn’t a barometer of the media’s behaviour or coverage or of India’s effort to help her neighbour.

(Anubha Bhonsle is the Executive Editor of CNN-IBN. The views expressed are her own)