Scores of students, belonging to different political organisations, protested in Chennai’s Valluvar Kottam on Tuesday demanding ‘Justice for Fathima Latheef’. But in the backdrop of raised fists and sloganeering, a purple curtain with numerous portraits bear testimony to just how rampant social discrimination and harassment is in campuses.

The pictures of now forgotten faces pinned up at the demonstration show that Fathima’s death is not the first of its kind, and why the spotlight should be on institutional murders and how institutions treat such deaths dispassionately.

These seven lives including Fathima are a reminder of why silence and brushing things under the carpet cannot be the norm.

Chuni Kotal, August 1992

The first woman to graduate from the Lodha Shabar tribe, Chuni Kotal, a 26-year-old adivasi took her own life on August 16, 1992 in Kharagpur. Belonging to a tribe that had been branded criminal by the British, Chuni, who was pursuing her MA in Anthropology, was subjected to years of caste-based discrimination and persecution, in particular by her Vidyasagar University professor Falguni Chakarvarti.

She was verbally abused in front of her peers, marked absent even when she was in class, and not allowed to sit for examinations. Despite multiple complaints, no action was taken.

It was only after Chuni’s story was published by writer Mahasveta Devi, thirteen days after her suicide, that it created a political uproar in West Bengal.

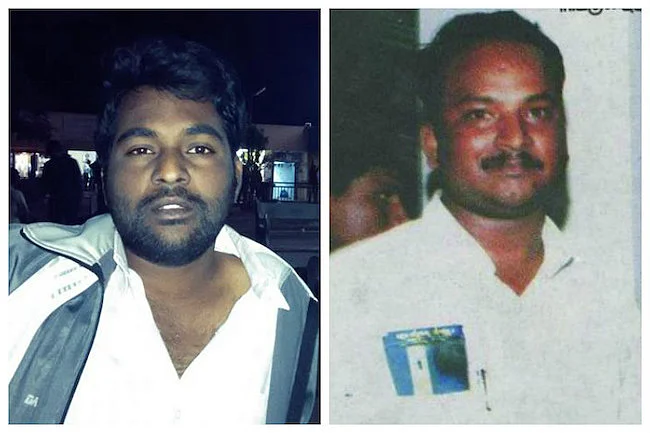

Senthil Kumar, February 2008

Pursuing his PhD in Physics in the Hyderabad Central University (HCU), Senthil Kumar, a Dalit student hailing from Salem in Tamil Nadu, killed himself in his hostel rooom on February 24, 2008. An internal fact-finding committee led by Professor Vinod Pavarala revealed how a culture of caste discrimination and prejudice had forced Senthil to take his own life.

Senthil, along with three other students belonging to the reserved categories were not assigned supervisors. Consequently, the 27-year-old failed in one of his subjects. As a result, he stopped receiving his fellowship stipend.

Unable to take the pressure, and with no guide to help him through the programme nor a fellowship to sustain his student life , Senthil Kumar, whose family reared pigs, killed himself.

Following his death, Senthil’s friend Thennarasu, a research scholar, had alleged systemic caste bias in HCU, claiming that supervisors would not take Dalit students, would delay evaluations and would raise the minimum pass mark to ensure they failed the subject, and be forced to discontinue the course.

Read Senthil Kumar’s story here.

Rohith Vemula, January 2016

The suicide of Rohith Vemula, a Dalit PhD scholar in HCU on January 17, 2016 shook the country’s collective conscience, trigerring widespread protests both inside the campus and outside. “My birth is my fatal accident,” he wrote in his suicide note, which went viral, revealing the deep-rooted caste prejudice and discrimination that Dalit students like him face.

Weeks before his death, Rohith and four other students were suspended after a student leader of the ABVP, RSS’s student wing, accused them of assaulting him. The issue was brought to the notice of the then Human Resources Development Minister Smriti Irani, who directed the university administration to look into the matter.

Rohith Vemula’s fellowship was suspended. The university then barred the five students including Rohith from entering the hostel or accessing any common area, although they were allowed to attend classes. Unable to afford renting a place outside, Rohith and the others pitched a tent on campus, they labelled ‘Velivada’ or Dalit ghetto.

He gave up his fight on January 17, 2016, taking his own life in a friend’s hostel room.

Read Rohith’s story here.

Dr Saravanan Ganesan, July 2016

Hailing from Tirupur in Tamil Nadu, 26-year-old Dr Saravanan Ganesan was found dead on July 10, 2016 in his New Delhi apartment under mysterious circumstances. The All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) student was found dead ten days after joining the MD in General Medicine programme.

After completing MBBS from Madurai Medical College, Saravanan qualified for the postgraduate Pathology programme in AIIMS. But with his heart set on General Medicine, Saravanan quit the course and began preparations for the AIIMS entrance exam. Securing the 47th rank, Saravanan was able to successfully pursue his General Medicine dream. But to his family and friends’ shock and horror, the young doctor was found dead with two syringes possibly containing potassium chloride, plastered in his arm.

While the Delhi police had first called his death a suicide, no note was left behind by Saravanan.

At the time, his father Ganesan, a tailor by profession, had alleged that Saravanan may have been a victim of the intense competition to get into AIIMS.

In December 2016, nearly five month after his death, the Delhi police registered a case of murder. However, no headway has been made in the case.

Read Saravanan’s story here.

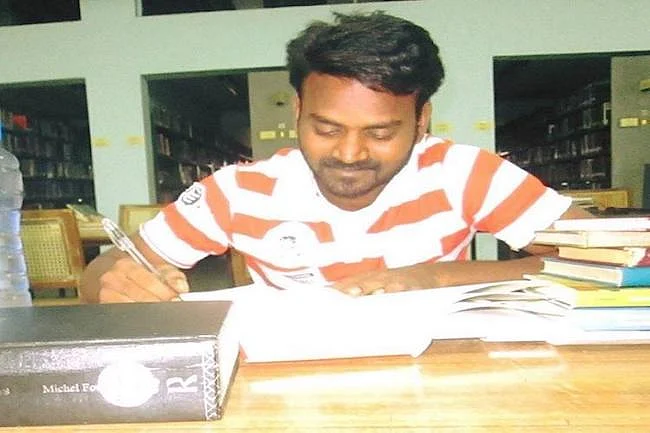

Muthukrishnan, March 2017

PhD scholar from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) Muthukrishnan killed himself on March 13, 2017 at his friend’s house in Delhi. His suicide was hauntingly similar to that of Rohith Vemula and Senthil Kumar, with questions of institutitional caste discrimination and bias raised.

A Facebook post published by Muthukrishnan three days before his death reads, “There is no Equality in M.phil/phd Admission, there is no equality in Viva – voce, there is only denial of equality, denying prof. Sukhadeo thorat recommendation, denying Students protest places in Ad – block, denying the education of the Marginal’s. When Equality is denied everything is denied (sic).”

Muthukrishnan was referring to the Sukhadeo Thorat-led committee, the first to study caste discrimination in higher education. In 2011, the committee came with a series of recommendations against caste-based discrimination in educational institutions, such as providing coaching classes for English fluency, social skills and communications, setting up an equal opportunity cell to help students qualify for the National Eligibilty Test among others.

The Sukhadeo Thorat committee recommendations are yet to be implemented.

Anitha, September 2017

In death, the 17-year-old Dalit girl from Ariyalur district, became a symbol of Tamil Nadu’s resistance to the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET). S Anitha, the daughter of a daily wage worker, took her own life on September 1, 2017 after she failed to secure a medical seat due to her poor NEET score.

Anitha’s dream of becoming a doctor turned to dust despite scoring 1176 out of 1200 in the Class 12 Board examinations. Her determination to secure an MBBS seat made her implead herself in the case challenging NEET in the Supreme Court that year.

But with no relief coming from the Supreme Court, and admissions based on the NEET score, Anitha was unable to join a medical course, having scored 86 out of 720. In one of her last interviews, Anitha had said, “From the village from where I am from, except for two or three people, no one wrote NEET. Even they didn’t make it. They are also talented. When people like us don’t have the means or opportunities to attend coaching classes, we can only prosper using what we have.”

Her suicide triggerred massive protests across the state, with students and political parties demanding that NEET be removed. Since Anitha’s death, many have argued that NEET is disadvantageous for those from poor households and rural backgrounds. This was substantiated by recent data submitted by the Tamil Nadu government to the Madras High Court. Only 2.1% of the students who had joined government and self-financing medical colleges in 2019 had passed NEET without enrolling in private coaching.

Read Anitha’s story here.

(This article was originally published by The News Minute and has been republished here with permission.)

(At The Quint, we are answerable only to our audience. Play an active role in shaping our journalism by becoming a member. Because the truth is worth it.)