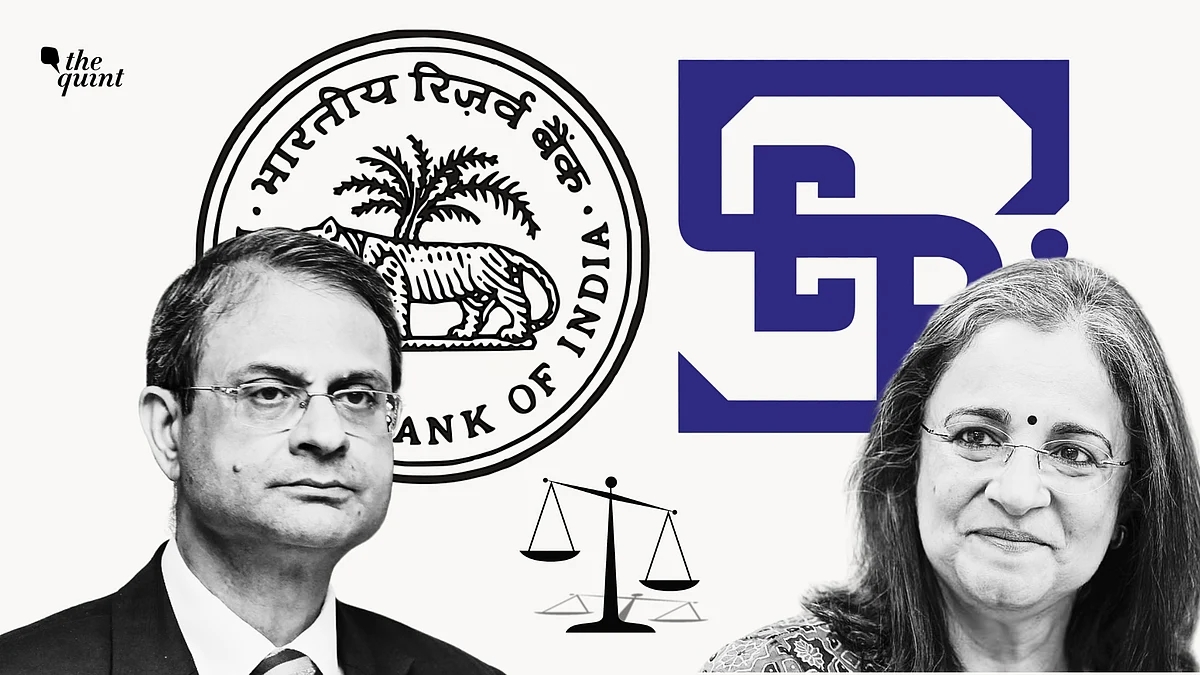

IAS Officers to Rescue: Why Modi Govt 'Prefers' Bureaucrats to Head RBI and SEBI

Should RBI-SEBI chiefs be IAS officers or professionals? The answer may depend on what purpose (or whom) they serve.

advertisement

After two thorough professionals, Raghuram Rajan and Urjit Patel, the government appointed an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer, Shaktikanta Das, as Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor in 2018. The government gave him a three-year extension and, in December 2024, replaced him with another IAS officer, Sanjay Malhotra.

After experimenting for the first time with an ace market professional Madhabi Puri Buch as the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) chief for three years, the government replaced her (denying her an otherwise normal extension) with yet another IAS officer, Tuhin Kanta Pandey, on 28 February.

Why has the government replaced financial sector specialists with generalist bureaucrats? Is the experiment with professionals over? What if the recently appointed IAS officers fail the markets?

IAS Ruled the Roost in ‘No Independence, No Conflict’ Era

The RBI was established in 1935 to take over the government’s currency function. After its nationalisation in 1949 and uptill mid-1990s, it acted more like a government agency - issuing currency, financing government deficits through ad-hoc treasury bills, managing public debt, setting administered interest rates, and regulating government-owned public sector banks.

The RBI governor needed no great knowledge of money and financial markets and independence from the government to carry out these functions. Instead, the most helpful qualification for the RBI governor was to know the government ministers and key finance ministry officials, coordinate with them, and discreetly carry out their wishes.

While there were occasional skirmishes (Benegal Rama Rau resigned following his public tiff with finance minister TT Krishnamachari), by and large, the will of the government prevailed and the governors functioned smoothly, including resigning when asked - sometimes without demur (Manmohan Singh), sometimes after trying appeasement tricks (KR Puri), or sometimes reluctantly, though without making any fuss (RN Malhotra).

1990s Reforms Created Conditions for Professionals

The shift to flexible exchange rates in 1991, the opening of Indian financial and banking to the private sector in 1992, the discontinuation of automatic budget financing by ad-hoc treasury bills from 1996, the opening up of equity and debt markets for foreign investors and other market reforms required the RBI governors to understand financial markets, interact with market participants, and be seen to be independent vis-à-vis the government in certain functions (for example, to bring credibility to inflation control caused by reckless government deficits).

This led to the selection and positioning of officers who, besides having vital governance and policymaking experience, could quickly master the job, learning in the Ministry of Finance and on the job. Appointment of ‘professionally qualified’ IAS officers (like YV Reddy and D Subbarao) and non-IAS civil servants (like Bimal Jalan) in the RBI for 20 years from the mid-nineties is explained by this emerging reality in ground conditions.

SEBI’s Origins Are More Governmental

The government regulated the equity markets directly until the early 1990s, administering the Securities Contract (Regulation) Act (SCRA) through the Department of Economic Affairs (DEA). The Controller of Capital Issues (CCI), usually an IAS officer, approved every capital issue, including share premium, if any, to be charged.

SEBI was first created through an administrative order in 1988. Even after its conversion into a statutory organisation in 1992, the SCRA continued to be under the direct control of the DEA, except for the extent of powers delegated.

It is quite understandable in the circumstances that SEBI has been mostly led by IAS officers (GV Ramakrishna, DR Mehta, M Damodaran, CB Bhave, UK Sinha, and Ajay Tyagi) after two sector specialists (SA Dave and SS Nadkarni) helped initially in setting it up. Only the other SEBI chief (GN Bajpai) was also a civil servant.

Many of these IAS officers knew very little of equity, debt, and derivatives markets initially as their previous jobs rarely required them to handle the markets and instruments. Most of them learnt their ropes while being posted in the Ministry of Finance before being appointed SEBI chiefs and mastered the art of markets and its regulations on the job.

SEBI’s developmental role (promoting depositories, demutualising stock exchanges, promoting market infrastructure, and so on) added to the utility of IAS officers’ relevance for heading SEBI. There were no open conflicts with the government — and no SEBI chief had to resign mid-term.

Government Experiments with Professionals in RBI

Raghuram Rajan, the first true professional to be appointed RBI governor in 2013 by the UPA government, did get some exposure to the government as Chief Economic Advisor (CEA). He initiated several markets and regulatory innovations to the RBI monetary policymaking and regulations of banks, including asset quality reviews (AQRs) of banks’ loan portfolios, which, after exposing a deep crisis of non-performing loans in the banking system, paved the way for strengthening of their capital base and profitability.

The Prime Minister, for various reasons, including his openly expressed preference to stymie the hold of IAS officers on important positions in the regulatory domain, decided to appoint Urjit Patel as the RBI governor in 2016.

Patel, a markets professional with extensive experience working in the International Monetary Fund (IMF), infrastructure financing companies, and a major Indian corporate – though without any government experience barring as a consultant – took over the RBI just before the demonetisation misadventure was carried out in November 2016.

Patel was seen as someone to be carrying out the government’s wishes.

Sometime in 2017, he decided to be seen as an independent RBI governor. He raised objections to the electoral bond scheme and had a tiff with the government on the issue before quietly conceding the case.

He also raised interest rates too high to the discomfort of the government and refused to do anything to alleviate foreign exchange stress that year.

The government tried to reason with him but had to make his life a little difficult when he did not see reason in whatever the finance minister suggested and failed to show any sensitivity towards the government. He was not asked to resign though.

He later tried to tone down his opposition to some issues (for example, by agreeing to refer the ECF issue to a committee). It was, however, too late. As pressure, including his own internal pressure, mounted on him, he gave up and resigned unexpectedly on his own.

Madhabi Buch Went Out Without Any Conflict with the Government

Madhabi Puri Buch had five years of excellent stint in SEBI as a full-time member. She continued to do a good job as a market regulator when she was appointed SEBI chief in 2022. She built good communication with market and market participants with her more open and engaging interactions in press conferences and other public events.

What perhaps triggered the decision not to renew her term or grant an extension was her indiscretions in her own financial, investment, and consulting matters. No justification provided by her could wash the taint of her running fully owned consulting firms while being a full-time SEBI member/chairperson, earning millions of rupees in consulting incomes. Her investments in suspect offshore vehicles and active handling of these accounts were also seen as highly questionable.

These indiscretions made her a liability to the government. Other successful market professionals are also likely to have financial and investment relationships coming in their way of independent functioning as SEBI chiefs. Understandably, this makes choosing another market professional as SEBI chief a high-risk matter for the government.

Back to IAS Again

The Modi government intends to keep a good grip over all important regulators whether in the governance domain (like the Comptroller and Auditor General or CAG) or financial sector regulators like the RBI and SEBI. It is easier to appoint an amenable IAS officer as a CAG since the role hardly needs any professional ability. For the RBI and SEBI, however, the government needs an IAS officer with professional ability, besides being completely committed to it.

Sanjay Malhotra is a highly intelligent IAS officer (topper of his batch) and has shown tremendous ability to acquire good a knowledge of financial and taxation business and policymaking. He was the CMD REC Ltd, Secretary Financial Services, and Secretary Revenue in the Ministry of Finance.

Tuhin Kanta Pandey is also quite a hardworking, patient and dependable IAS officer. He spent five years as Department of Investment and Public Asset Management (DIPAM) secretary with disinvestment and privatisation practically abandoned in the last three years when the government effectively changed the policy in 2022. Just a little while earlier, he professionally managed the privatisation of Air India in 2022 in a single bid when the government wanted to get Air India off its back.

In his short tenure of Revenue Secretary, the government could ‘persuade’ the reluctant bureaucracy to give away Rs 1 lakh crore to Rs 1 crore income tax payers in the midst of Delhi elections, hollowing out India’s taxpayer base to barely 1 percent of the population.

Both these officers are likely to do a good job and are unlikely to create any perceptional or real difficulties for the government.

What if the Sea Turns Turbulent and the Sky Keeps Falling?

Given the state of the global and domestic financial markets, it is not unlikely that the RBI will not face a crisis of further fall in foreign exchange reserves and depreciation of rupee. Declining external commercial borrowings (ECBs), foreign direct investment (FDI) turning into a trickle and FPIs making relentless selling are likely to add more to RBI’s difficulties.

Without complete professional independence to deal with such situations, there is a good possibility that Sanjay Malhotra may not come out on top of it and Indian companies, investors and markets face unprecedented losses. This will make the government decidedly uncomfortable.

This is not a necessary scenario. Things may stabilise and markets may start recovering. What if, however, such a situation arises and Tuhin Kanta Pandey is not able to stem the rot?

Given the experience and political preference, the Modi government is unlikely to appoint market professionals to manage the RBI and SEBI. The government will most likely persist with both the regulators. If and when it becomes unsustainable, the government may find other more skilled IAS officers/civil servants to do the job.

(Subhash Chandra Garg is the Chief Policy Advisor, SUBHANJALI, and Former Finance and Economic Affairs Secretary, Government of India. He's the author of many books, including 'The $10 Trillion Dream Dented, We Also Make Policy, and Explanation and Commentary on Budget 2024-25'. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined