Unboxing Trump's Tariff Rationale: Fortress America Seeks Solace in the Past

The economic rationale of the enhanced import tariffs is puzzling, writes Sanjeev Ahluwalia.

advertisement

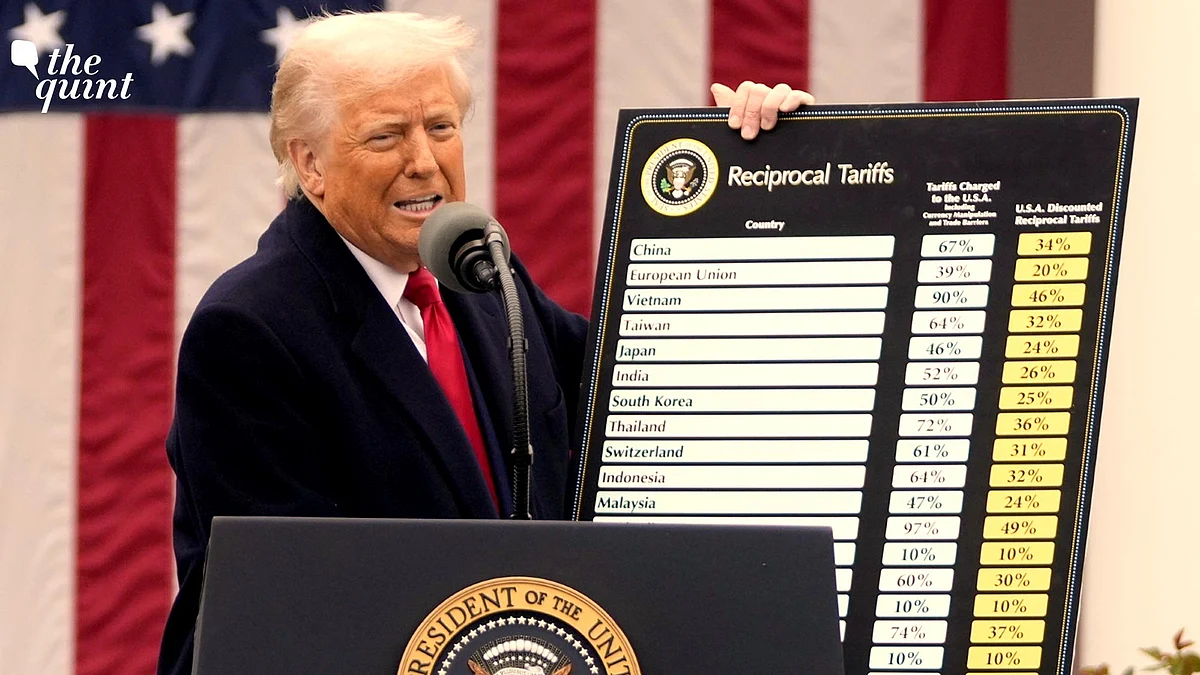

US President Donald Trump’s “kind and reciprocal” import tariffs, applied at about one half of the average rate charged by each country for imports from the US—as estimated by the Trump team—are a curiously "simple", America-centric concept.

They draw inspiration from the 1930s, even while disregarding the enormous complexity of global trade, investment and security ecosystems a century since, and the role of institutions—some, like the World Trade Organisation, now rendered comatose.

Since the objective is to reduce imports and not kill them entirely, only one half of the calculated rate is being proposed presently which is sufficient to halve the trade deficit. Whether this will also reduce exports and kill domestic demand for more costly imports or divert trade away from America entirely, are known unknowns.

Some strategically critical imports like semi-conductors, energy and pharmaceuticals are exempt and this list might grow in future. Indian pharma exports are consequently undisturbed.

Soft on India?

India—courtesy its business potential as the fastest growing democracy, or its strategic potential as an ally in an anti-China coalition, or because of the friendship between Prime Minister Modi and President Trump—seems to have gotten off lightly.

The reciprocal average rate is 26 percent, or one half of 52 percent the calculated average tariff across all products that would reduce the trade deficit with India.

Close American ally Vietnam, which grew rapidly in recent years on the back of exports, and where the American trade deficit is US $122 billion, almost three times the trade deficit in India, faces an import tariff of 46 percent. Bangladesh, with a trade deficit of only 15 percent of India’s, faces a tariff of 37 percent China with a trade deficit more than double of India’s, faces a tariff of 34 percent.

India—courtesy its business potential as the fastest growing democracy, or its strategic potential as an ally in an anti-China coalition or because of the friendship between Prime Minister Modi and President Trump—seems to have gotten off lightly.

To what extent this disruption is likely to alter the flow of exports, away from the US to other destinations, will be known only over time, as traders redesign their networks to maximise profits.

Importing Inflation by Taxing Domestic Consumers

Commonsensically, the basic minimum import tax of 10 percent (versus the average of 3.3 percent earlier) is actually a tax on the American consumer or producer importing intermediate products.

Higher tax on imports worth US$ 3.3 trillion could add US $660 billion to costs generating additional inflation potential of two percentage points pushing inflation in America back to over four percent. This will put the US Federal Reserve in a quandary of whether to abandon its phased reduction of interest rates or actively revert to higher interest rates and risk impeding fresh investment.

Even the minimum additional import tax of 10 percent could seriously compromise the economics of exporting low value products to the US (garments, for example), where the margins are slender for exporters.

Luxury goods—high end automobiles, fashion ware, designer labels—where the margins are high, could still survive. But trans-Atlantic or trans-Pacific shopping trips are likely to become popular amongst Americans, much like Indians visit Dubai or Thailand or like Europeans earlier enjoyed shopping in “dirt cheap” America.

Back to Grunt Work

The economic rationale of the enhanced import tariffs is puzzling. The intention is to make America great again by reversing the decline in the share of manufacturing from 17 percent of GDP in 1997 to 11 percent in 2024.

This is conflated with national security and recovery of the 5 million jobs lost in manufacturing versus the burgeoning “burger flipping” variety, which keep unemployment low in the US at about 4.1 percent. For good measure, making American agriculture self-sufficient to feed America in an emergency is also tagged as national security concern.

The dominance of the US dollar was not because of efficient manufacturing – a role ceded long back as it moved up the value addition chain to financial and tech innovation.

iPhone manufacturing, and assembly contribute just 28 to 41 percent of the total cost while Apple’s software development and proprietary services contribute the bulk of the value addition, benefiting knowledge workers and companies. Not those doing the grunt work of mining, refining and producing the materials and metals which go into making the iPhone.

Hits and Misses

Fortress America will dissuade the deepening of global business and trade links which form the basis of America’s global outreach and influence.

What is certain though, is that they will kick-start a domino effect of new alliances and supply chains as American trade policy mimics the uncertainty and retroactivity, more common in developing economies, which follow rather than lead.

Those already invested in global supply chains will lose via disruption of the existing arrangements. Those only marginally integrated into global supply chains will likely benefit—like India—despite red flags from this disruption.

It is unwise to rely on the political goodwill of large trading partners to boost the paltry share of goods exports in India’s GDP. India is already too big and getting bigger by the day, to be saved by anyone, except itself.

(Sanjeev S Ahluwalia is a Distinguished Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation [CRF], a former IAS officer and an expert in governance and economic regulation. This is an opinion piece. All views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: 05 Apr 2025,09:42 AM IST