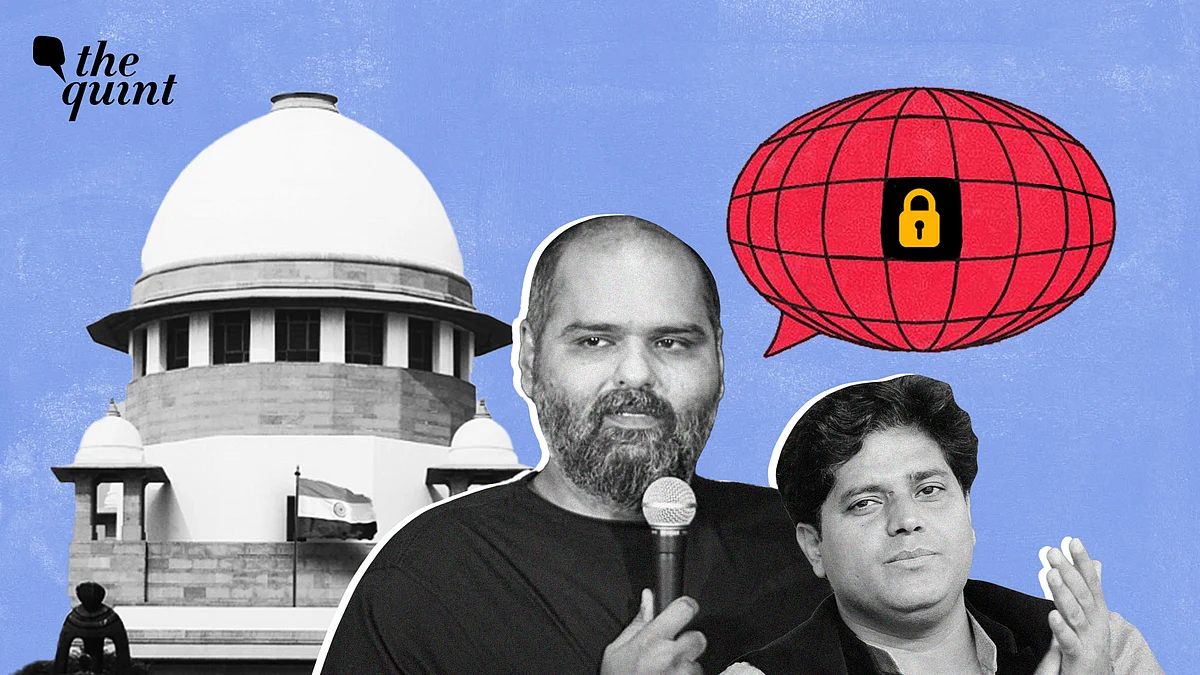

State vs Satire: Imran Pratapgarhi, Kunal Kamra & India's Free Speech Conundrum

Tolerance is not a virtue that flourishes naturally—it must be cultivated, legally enforced, and socially upheld.

advertisement

The Indian Constitution guarantees a bundle of rights to its citizens, and in certain situations, even to foreigners. Part III of the Constitution outlines fundamental rights, which can be invoked only against state actions or authorities falling under the definition of 'state' under Article 12.

From comedians like Kunal Kamra invoking the Constitution as his shield to courts simultaneously condemning 'dirty' language while safeguarding poetic dissent, the legal landscape remains uneven. As the Supreme Court itself has emphasised, free speech is the lifeblood of democracy—but are we, as a society, still willing to tolerate voices that challenge, provoke, or simply make us uncomfortable?

The recent crackdown on free speech, comedy, and art, and the legal system's vacillations on the same, is a stark reminder of the increasing intolerance in society and the judiciary or legal system's inability to define free speech.

Let us consider two instances—the Imran Pratapgarhi case and the Kunal Kamra controversy—to understand the tussle within the Indian legal system's attitude with regard to free speech.

A Poem That Became a Crime

Rajya Sabha MP Imran Pratapgarhi faced criminal charges after reciting a poem at a public event in Jamnagar. The poem, which was later shared on social media, allegedly contained provocative language that some interpreted as inciting communal discord.

A complaint was filed accusing the poem of promoting enmity between communities and threatening national unity, leading to an FIR under various sections of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), including charges related to incitement and public disorder.

Pratapgarhi challenged the FIR in court, arguing that the poem was protected under free speech. While the police claimed that the lyrics could inflame tensions, his defence maintained that it was an artistic expression. The matter escalated to the Supreme Court, which ultimately quashed the proceedings, reinforcing that unpopular or critical speech cannot be criminalised unless it directly incites violence—a significant victory for free expression.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Imran Pratapgadhi vs. State of Gujarat and Anr significantly expanded the scope of free speech. The bench came down heavily on the police and state authorities for lodging a criminal case against Pratapgadhi for a poem he recited during an event.

In its judgment, the bench underscored the importance of protecting the freedom of speech and expression and reminded the Courts and the Police of their duty to uphold the rights of persons expressing unpopular opinions.

Significantly, the bench of Justices Oka and Ujjal Bhuyan said that even if a large number of persons dislike the views expressed by another, the right of person to express the views must be respected and protected. Literature, including poetry, dramas, films, satire, and art, make the life of human beings more meaningful, the court said.

The Supreme Court also observed that the poem does not refer to any religion, caste or language and neither refers to any persons belonging to any religion.

It said that it is the bounden duty of the courts to ensure that the Constitution and ideas of the Constitution are trampled upon. It concluded that the courts “must remain ever vigilant to thwart any attempt to undermine the Constitution and the constitutional values, including the freedom of speech and express.”

This ruling aligns with a landmark Bombay High Court decision in Anand Chintamani Dighe & Anr vs. State of Maharashtra & Ors. Over two decades ago, the Court held that tolerance of a diversity of viewpoints and the acceptance of the freedom to express of those whose thinking may not accord with the mainstream are cardinal values which lie at the very foundation of a democratic form of Government.

The court observed as follows: A society wedded to the rule of law, cannot trample upon the rights of those who assert views which may be regarded as unpopular or contrary to the views shared by a majority.

Similarly, in Shreya Singhal vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court struck down Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, reaffirming that liberty of thought and expression is a cardinal value that is of paramount significance under the Constitution scheme and it the most basic human right.

The Hanging Habitat: Kunal Kamra’s Stand-up

The verdict becomes all the more important when seen in contrast with the recent police and political crackdown on comedy. What started as moral outrage and subsequent FIRs over so-called lewd jokes made by influencer-comics on an online show snowballed into a full-blown clampdown on free speech after stand-up Kunal Kamra’s alleged defamatory remarks against Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Eknath Shinde and other political leaders. The video led to an FIR being filed against Kamra. Shortly after the YouTube video was uploaded in March, the venue where Kamra performed—the Habitat Studio in Mumbai—was vandalised, allegedly by workers associated with Shinde.

Even after the backlash from the political leaders, Kamra said that he would not apologies for his comments and criticised the “inability to take a joke at the expense of a powerful public figure.”

Before the Habitat attack, the country was roiled in the controversy that had erupted around the show India’s Got Latent and its attendees, who were made part of the investigation after guest Ranveer Allahabadia made an allegedly offensive remark while questioning a participant. Following this, there was a crackdown on the show, and criminal cases were registered against the organisers as well as the attendees, who just came to watch the show.

When the matter reached the Supreme Court on 3 March, a bench led by Justice Surya Kant granted Allahabadia protection from arrest, but imposed a condition barring him from airing any shows for the time being.

Popular Outrage Cannot Dictate Constitutional Rights

Free expression of thoughts and views by individuals or group of individuals is an integral part of a healthy civilised society.

Without freedom of expression of thoughts and views, it is impossible to lead a dignified life, as guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court in Imran Pratapgadhi (Supra) clearly held that in a healthy democracy, the views, opinions, or thoughts expressed by an individual or group of individuals must be countered by expressing another point of view.

While there are some judges who prefer personal morality over constitutional morality, in Imran Pratapgadhi (Supra), the Supreme Court made it very clear that the Courts are duty-bound to uphold and enforce fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution of India.

“Sometimes, we, the Judges, may not like spoken or written words. But, still, it is our duty to uphold the fundamental right under Article 19 (1)(a). We Judges are under an obligation to uphold the Constitution and respect its ideals. If the police or executive fail to honour and protect the fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 19 (1)(a) of the Constitution, it is the duty of the Courts to step in and protect the fundamental rights. There is no other institution which can uphold the fundamental rights of the citizens.”

Tolerance is not a virtue that flourishes naturally—it must be cultivated, legally enforced, and socially upheld. As the Bombay High Court wisely observed decades ago, popular outrage cannot dictate constitutional rights.

The courts must remain steadfast in their role as guardians of dissent, ensuring that the state does not weaponise laws to punish mere offence. After all, a democracy that cannot laugh, criticise, or question, is one that has already lost its way. The choice is simple: either we defend the messy, irreverent chaos of free expression—or we surrender to the silence of conformity.

(Areeb Uddin Ahmed is an advocate practicing at the Allahabad High Court. He writes on various legal developments. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined