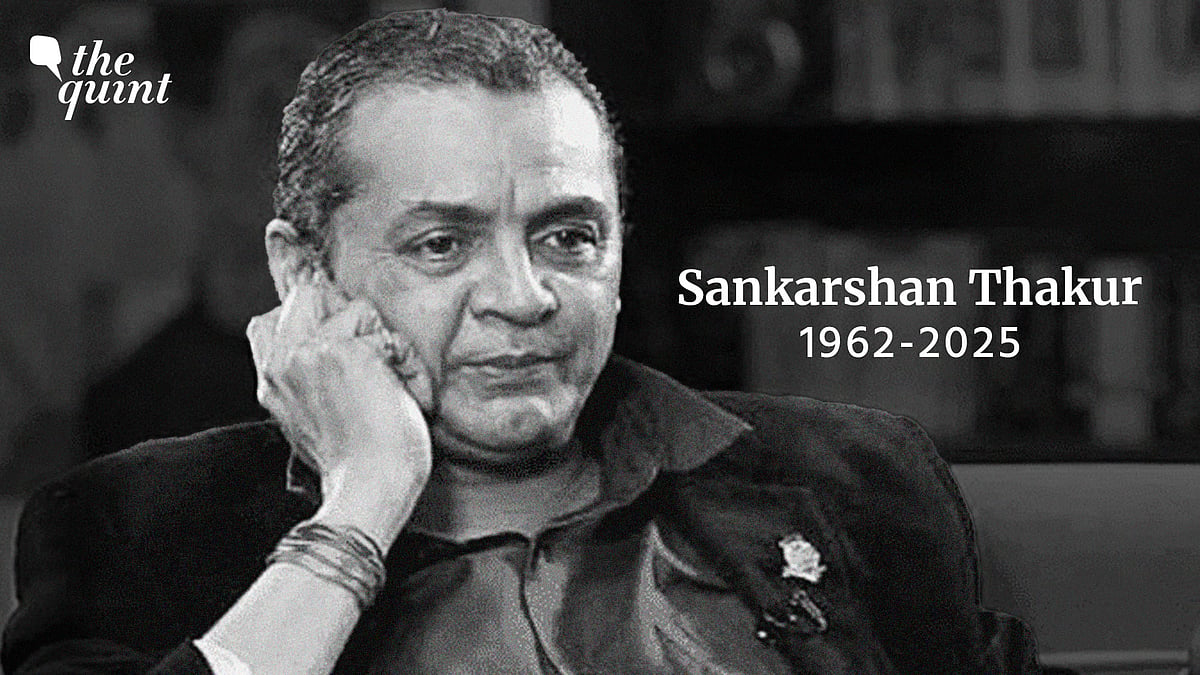

Remembering Sankarshan: The Reporter-Editor Who Kept Journalism First

Sankarshan Thakur was a product of a time when journalism was not a profession or career, but a mission and passion.

advertisement

“I was employed with The Telegraph since the age of 10.”

That was Sankarshan Thakur, who lived and died a scribe and had journalism coursing through his veins.

Someone like me - a first-generation journalist - could probably never understand his love and fascination for this noble profession. His father Janardan Thakur was a well-known journalist too and had written many books, including ‘All The Janta Men,’ and was working with Hindustan Standard then, an Anand Bazar Patrika Publication. This was before The Telegraph was even born.

In those pre-communication-revolution days when information flow was not instant, the teleprinter was the machine through which news used to reach the newspaper’s office. A young Sankarshan, at age 10, would to go to his father’s office and play with the teleprinter. He used to be fascinated by that machine. He would fetch news from the teleprinter and run towards his father with it.

I can’t claim that he was my friend, per se, or that I knew him intimately. We knew each other well and were aware of each other’s writings and political positions. He was aware of my temporary association with the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) after more than a two-decade-long journalistic career, and at times we did chat on the phone whenever he wanted to know something about the politics of the AAP. But in that capacity, I knew him to be a fierce journalist unlike any other.

A Reporter-Editor Like No Other

The last time I called him was a few months back, when he was made editor of The Telegraph. I wanted to invite him on my digital platform, Satyahindi to discuss his book on Nitish Kumar. He was busy but promised to speak with me soon. Unfortunately, time flew by and we could never meet in person.

Sankarshan was the first reporter-editor for The Telegraph. Before that, the newspaper had a tradition of appointing desk men and women as editors. He was undoubtedly a great reporter, and his reports used to surprise a person like me every time I read them.

As a reporter, he had a vast experience of reporting from global conflict zones such as Kabul and the Middle East. His special fascination with covering Pakistan, led him to visit the country many times as a reporter. Within the country, he took a special interest in the politics of Kashmir, but his first love was always Bihar. It is no wonder he wrote so many books on the state, enlightenings readers about the point of views of two of the state's main political protagonists, Lalu Prasad Yadav and Nitish Kumar.

In today’s world, where not reading is a virtue and meeting political leaders is a godsend opportunity, Sankarshan preferred to read a book and then go on to help his fellow reporters find a quote from the book. Or just work silently behind the scenes to make a good copy better.

Thakur was known for his political reporting. But not many appreciate that he was also a fantastic feature writer. Even after becoming the editor of The Telegraph, he would personally guide the features team and take particular interest in their work.

Even when he was in the hospital after being diagnosed with cancer, I am told that he used to work closely with his team and would sketch for the feature stories sometimes. He was, in fact, skilled at sketching and painting. That's another thing not many people knew about him, except perhaps his close friends.

Battle with Cancer

I don’t know why he quit smoking. I won’t call him a chain smoker, but he used to smoke a lot, and it was rare not to see him without a cigarette. Five years back, he suddenly stopped smoking and would tell his friends how easy it was to quit. Once he quit the habit, he was not tempted to start again even once.

I have no information if he had the premonition about the future or whether was advised by doctors, but he would often reminisce about the time when journalists could smoke in the office instead of filing outside to smoke, per the norm now.

I did not know that he was suffering from lung cancer, and so his death came as a surprise to me. He was diagnosed a few months back and was very confident that it would be cured. He told his close friends and colleagues that there was nothing to worry about him. I am told that he was so much in love with his work that the time after his first chemotherapy was the only time when he did not attend the office for a week due to his illness. On most days, he used to work late into the night, texting or emailing colleagues about work, at times as late as 2 AM.

This was also the time of the great editors, when political stalwarts would feel lucky to meet editors in their offices.

Sankarshan became editor at a time when the institution of editor had been annihilated by the force of history; corporate interests conspired to substitute profit motive with editorial independence. When politics decided to make journalism pulp fiction, and ideology pressured to create pre-programmed living robots pretending to be press persons.

With his appointment, it was expected that he would moderate the tone of the paper and bring back the equilibrium to its original point.

A Legacy of Tradition and Rebellion

Sankarshan was a legacy journalist to the core and believed that ideology should not blur the line between likes and dislikes. He knew it was the job of an editor to remain unaffected and maintain neutrality between the government and the Opposition, and he did it with aplomb.

But that does not mean he ever compromised his old-fashioned journalistic values. He remained fiercely independent and irreverent. When the Election Commission held a press conference to dispel any impression about its partisanship, The Telegraph came out with a headline—'Election Omission'—that said it all.

With his departure, journalism has lost a man represented a great mix of tradition and rebelliousness.

Sankarshan never flinched from calling a spade a spade. He was never enamoured with the power politics despite closely observing the play of power in its highest corridors. He was a voice of sanity in an era of insanity; he was not de-ideologised but ideology did not blind his vision. He was committed to journalism till his last breath, and he was a proud Bihari who loved to cook mutton and relish every bit of it.

In the end I would quote the words of his colleague Devdan Mitra, written after his demise:

Sankarshan, today I wish to call you my friend. People like me will miss you, always. You left a void in us. You left us when we needed you the most.

(Ashutosh is a journalist and former politician with AAP. He was one of the founding members of the party. This is an opinion piece. All views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined