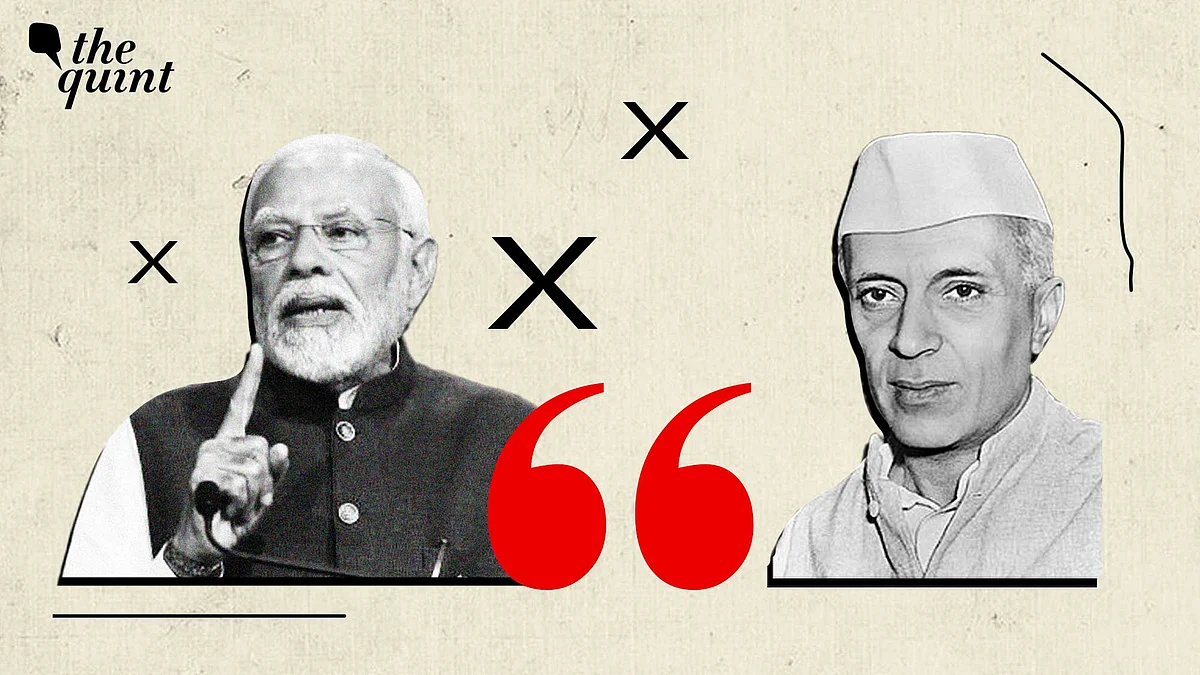

Why Modi’s Comment On Nehru’s Reservation Policy Doesn’t Pass The ‘History Test’

PM Modi's criticism of Jawaharlal Nehru's position on reservation is based on incomplete information.

advertisement

On 14 December, while delivering the concluding remarks on the debates over the constitution in Lok Sabha, Prime Minister Narendra Modi again went after his pet target - former PM Jawaharlal Nehru. On the one hand, he slammed the first PM for bringing the first constitutional amendment that imposed restrictions on the freedom of speech and expression, on the other, he evoked the issue of reservation, saying that Nehru was against it.

This is, however, not the first time that PM Modi attacked Nehru for his views on reservation. Before the Lok Sabha elections, addressing the motion of thanks, Modi said, “Nehru ji used to say that if SC/ST/OBC got quotas in jobs, then the standard of government work would fall.”

He was referring to a letter that Nehru wrote to Chief Ministers on 27 June, 1961. Reflecting on his concerns over ‘national integration’, he spoke of the necessity of “getting out of the old habit of reservations and particular privileges being given to this caste or that group.” He also expressed his displeasure over ‘inefficiency and second-rate standards’.

But this letter only provides a small part of Nehru’s broader views on reservation. It is anachronistic to quote him without putting the words into the historical context. Rather, to understand Nehru’s actual views on reservation, one must go back to the Constituent Assembly debates.

What Jawaharlal Nehru Said During the Constituent Assembly Debates

While moving the Objectives Resolution on 13 December, 1946 - that later shaped both the preamble and the Constitution - Nehru placed eight clauses, of which clause No. 6 reads, “WHEREIN adequate safeguards shall be provided for minorities, backward and tribal areas, and depressed and other backward classes.” He was not very fond of the word caste. Instead, he used class to refer to social and economic backwardness.

Scholar Benjamin Zachariah, in one of his articles, points out how clauses 5 & 6 ‘were at the core of the social engineering project of a 'new India', and a clear indication of what is in retrospect seen as the Nehruvian project.’ Clause 5 promised social, economic and political equality and justice to every Indian, irrespective of social and religious status.

Interestingly, at that point, Nehru was trading through an ideological slippery slope. His progressive accolades were very few in number in the Constituent Assembly. He was supposed to take his flock towards a ‘modern nation’ that thrives on its ancient roots. In objective resolutions, he tried to find the remedy. Through clauses 5 & 6, while he addressed the aspiration of the modern nation, clause 8 evoked the imagination of an ‘ancient land’, placating his detractors. Promises of safeguards, which can be read as affirmative actions as well, to the backward classes and minorities became one of the major fulcrums of the ‘new India’.

The Question of the First Amendment

The first constitutional amendment that PM Modi also invoked to attack Nehru has a prominent instance that shows his stance in favour of reservations. Since the Montague-Chelmsford reforms of 1919, both the Bombay and Madras presidencies had followed the reservation policy. In 1921, the Madras government passed an order governing the shares of quota in college admissions. According to the order, out of 14 seats, six were for non-Brahmin Hindus, two for backward caste Hindus, two for Brahmins and the rest for the non-Hindu communities.

When the Congress government came to power, it continued with the prevailing reservation policy. However, a controversy broke out as a Brahmin student, Champakam Dorairajan, sought admission to a medical college but couldn’t get it allegedly due to the reservation policy. She filed a petition in the Madras High Court and claimed that the pre-independence government order that the Congress government upheld was in violation of Articles 15 (1) and 29 (2) of the Indian constitution.

Despite the passionate arguments of the Advocate General of Madras, who asked the court to read Article 29 with Article 46 (promote the educational and economic interests of the SCs, STs and other weaker sections of the society), which is part of the directive principles, both the Madras HC and the Supreme Court scrapped the order as ultra-vires.

Chief Minister of Madras Kumar Swami Raja requested the Union Government to amend the Constitution to protect the interests of backward classes. And the parliament paid heed to it.

Though Article 16 (4) was already there in the Constitution, allowing provisions of reservations for the backward classes if they were not represented properly in government jobs, a new article was needed legitimising the abilities of the states to come up with specific provisions needed for the advancement of SCs, STs and any socially and economically backward classes.

So, after discussions, Article 15 (4) was inserted, noting, “Nothing in this article or clause (2) of Article 29 shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes.” This amendment also brought in a new category, ‘backward classes,’ apart from the SCs and STs. One must not forget that Nehru was the leader of the house at this crucial juncture.

Following the mandate of Article 340 that was passed on 26 January, 1950, the first backward classes commission was appointed under the chairmanship of Gandhian Kaka Kalelkar. The committee, in its report, listed 2,399 castes and pointed out that 32% of the Indian population needed affirmative action due to their social and economic backwardness. However, Nehru’s Home Minister, GB Pant, was not happy with the report. Rejecting the caste-centred survey, he said, “The recognition of the specified castes as backward may serve to maintain and even perpetuate existing distinctions based on caste”.

On 3 September, 1956, the government tabled the report, but it was never discussed. Nehru started believing that there was no need for a separate OBC category. It was in this context that Nehru wrote that letter to the CMs that PM Modi has been referring to.

In the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, if anything had hurt the BJP the most, it is the caste conundrum. The campaign of Congress that the ruling party would change the Constitution and abolish the reservation resonated well among the marginalised. The party has learnt an important lesson- ‘you can play with anything but the sentiment of reservation’. The repetitive attacks on Nehru regarding reservation are a byproduct of such lesson or fear.

In a true sense, it doesn’t matter now whether Nehru was in favour of reservation or not. What matters the most is the sincerity of the current government in implementing existing legal frameworks. Caste-census is a good pitch to start with. Will PM Modi at least show the courage to find out the social and economic reality of different castes? History will take care of Nehru. The PM can focus on the present and the future.

(The author is a Delhi-based journalist and academic. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined